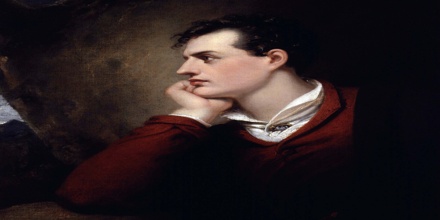

Lord Byron

(British Poet, Politician, and a Leading Figure in the Romantic Movement)

Full name: George Gordon Byron

Date of birth: 22 January 1788

Place of birth: London, England

Date of death: 19 April 1824 (aged 36)

Place of death: Missolonghi, Aetolia, Ottoman Empire (present-day Aetolia-Acarnania, Greece)

Resting place: Church of St. Mary Magdalene, Hucknall, Nottinghamshire.

Occupation: Poet, politician

Nationality: English

Spouse: Anne Isabella Byron, Baroness Byron (m. 1815–1816)

Children: Ada Lovelace, Allegra Byron, Elizabeth Medora Leigh

Early Life

Lord Byron, in full George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron was born on January 22, 1788, in London, England He was a British Romantic poet and satirist whose poetry and personality captured the imagination of Europe. Renowned as the “gloomy egoist” of his autobiographical poem Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage (1812–18) in the 19th century, he is now more generally esteemed for the satiric realism of Don Juan (1819–24). He travelled extensively across Europe, especially in Italy, where he lived for seven years with the struggling poet Percy Bysshe Shelley. Later in his brief life, Byron joined the Greek War of Independence fighting the Ottoman Empire, for which many Greeks revere him as a national hero.

He died in 1824 at the age of 36 from a fever contracted while in Missolonghi. Often described as the most flamboyant and notorious of the major Romantics, Byron was both celebrated and castigated in life for his aristocratic excesses, including huge debts, numerous love affairs – with men as well as women, as well as rumours of a scandalous liaison with his half-sister – and self-imposed exile.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Born George Gordon Byron (he later added “Noel” to his name) on January 22, 1788, Lord Byron was the sixth Baron Byron of a rapidly fading aristocratic family. A clubfoot from birth left him self-conscious most of his life. As a boy, young George endured a father who abandoned him, a schizophrenic mother and a nurse who abused him. As a result he lacked discipline and a sense of moderation, traits he held on to his entire life.

Byron received his early formal education at Aberdeen Grammar School, and in August 1799 entered the school of Dr. William Glennie, in Dulwich. Placed under the care of a Dr. Bailey, he was encouraged to exercise in moderation but could not restrain himself from “violent” bouts in an attempt to overcompensate for his deformed foot. His mother interfered with his studies, often withdrawing him from school, with the result that he lacked discipline and his classical studies were neglected.

In 1801 he was sent to Harrow, where he remained until July 1805. An undistinguished student and an unskilled cricketer, he did represent the school during the very first Eton v Harrow cricket match at Lord’s in 1805.

From 1805 to 1808, Byron attended Trinity College intermittently, engaged in many sexual escapades and fell deep into debt. During this time, he found diversion from school and partying with boxing, horse riding and gambling. In June 1807, he formed an enduring friendship with John Cam Hobhouse and was initiated into liberal politics, joining the Cambridge Whig Club.

Personal Life

In 1803, Byron fell deeply in love with his distant cousin, Mary Chaworth, and this unrequited passion found expression in several poems, including “Hills of Annesley” and “The Adieu.”

In July 1811, Byron returned to London after the death of his mother, and in spite of all her failings, her passing plunged him into a deep mourning. High praise by London society pulled him out of his doldrums, as did a series of love affairs, first with the passionate and eccentric Lady Caroline Lamb, who described Byron as “mad, bad and dangerous to know,” and then with Lady Oxford, who encouraged Byron’s radicalism. Then, in the summer of 1813, Byron apparently entered into an intimate relationship with his half sister, Augusta, now married. The tumult and guilt he experienced as a result of these love affairs were reflected in a series of dark and repentant poems, “The Giaour,” “The Bride of Abydos” and “The Corsair.”

In September 1814, seeking to escape the pressures of his amorous entanglements, Byron proposed to the educated and intellectual Anne Isabella Milbanke (also known as Annabella Milbanke). They married in January 1815, and in December of that year, their daughter, Augusta Ada, better known as Ada Lovelace, was born. However, by January the ill-fated union crumbled, and Annabella left Byron amid his drinking, increased debt, and rumors of his relations with his half sister and of his bisexuality. He never saw his wife or daughter again.

By 1818, Byron’s life of debauchery had aged him well beyond his 30 years. He then met 19-year-old Teresa Guiccioli, a married countess. The pair were immediately attracted to each other and carried on an unconsummated relationship until she separated from her husband. Byron soon won the admiration of Teresa’s father, who had him initiated into the secret Carbonari society dedicated to freeing Italy from Austrian rule. Between 1821 and 1822, Byron edited the society’s short-lived newspaper, The Liberal.

He enjoyed adventure, especially relating to the sea. Byron had a great love of animals, most notably for a Newfoundland dog named Boatswain. When the animal contracted rabies, Byron nursed him, albeit unsuccessfully, without any thought or fear of becoming bitten and infected. During his lifetime, in addition to numerous cats, dogs, and horses, Byron kept a fox, monkeys, an eagle, a crow, a falcon, peacocks, guinea hens, an Egyptian crane, a badger, geese, a heron, and a goat. Except for the horses, they all resided indoors at his homes in England, Switzerland, Italy, and Greece.

Writing Career

In 1807 Byron published his first book of poetry, Hours of Idleness. In the preface he apologized, “for obtruding forcing myself on the world, when, without doubt, I might be at my age, more usefully employed.” The book was harshly criticized by the Edinburgh Review. Byron counterattacked in English Bards and Scotch Reviewers (1809), the first manifestation sign of a gift for satire (making fun of human weaknesses) and a sarcastic wit (making fun of someone or something in a harsh way by saying the opposite of what is meant), which singled him out among the major English romantics, and which he may have owed to his aristocratic outlook and his classical education.

In 1809 a two-year trip to the Mediterranean countries provided material for the first two cantos (the main divisions of long poems) of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage. Their publication in 1812 earned Byron instant glory. They combined the more popular features of the late-eighteenth-century romanticism: colorful descriptions of exotic nature, disillusioned meditations on the vanity of earthly things, a lyrical exaltation of freedom, and above all, the new hero, handsome and lonely, yet strongly impassioned even for all of his weariness with life.

The first two cantos of Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage were published in 1812, and were received with acclaim. In his own words, “I awoke one morning and found myself famous”. He followed up his success with the poem’s last two cantos, as well as four equally celebrated “Oriental Tales”: The Giaour, The Bride of Abydos, The Corsair and Lara. About the same time, he began his intimacy with his future biographer, Thomas Moore.

From then on the theme of incest was to figure strongly in his writings, starting with the epic tales (long poems that tell stories) that he published between 1812 and 1816: The Giaour, The Bride of Abydos, The Corsair, Lara, The Siege of Corinth, and Parisina. According to Byron, incestuous love, criminal although genuine and irresistible, was a suitable metaphor (symbol) for the tragic condition of man, who is cursed by God, rebuked (judged harshly) by society, and hated by himself because of sins for which he is not responsible. The tales, therefore, add a new dimension of depth to the Byronic hero: in his total alienation (separation from one’s surroundings) he now actively takes on the tragic fatality that turns natural instinct into unforgivable sin, and he deliberately takes his rebellious stand as an outcast against all accepted beliefs of the right order of things.

In Switzerland Byron spent several months in the company of the poet Percy Bysshe Shelley (1792–1822). Under Shelley’s influence he read William Wordsworth (1770–1850) and immersed himself in the unpleasant spirituality that permeated the third canto of Childe Harold. But The Prisoner of Chillon and Byron’s first drama, Manfred, took the Byronic hero to a new level of inwardness: his greatness now lay in the refusal to bow to the hostile powers that oppressed him, whether he discovered new selfhood in his very dereliction (negligence) or sought the fulfillment of his assertiveness in self-destruction.

In October 1816 Byron left for Italy and settled in Venice. His compositions of 1817, however, show signs of a new outlook. Spontaneous maturation (growing up) had thus paved the way for the healing influence of Teresa Guiccioli, Byron’s last love. The poet had at last begun to come to terms with his desperate idea of life.

It is characteristic of Byron’s strength of character that he increasingly sought to translate his ideas into action, repeatedly voicing the more radical Whig (a political party in England that supported reform in government and society) viewpoint in the House of Lords in 1812–1813. He also ran real risks to help the Italian Carbonari (a secret group in Italy that worked for a representative government based on a constitution) in 1820–1821. His early poetry had contributed to sensitizing the European mind to the struggle of Greece under Turkish rule.

In 1823, a restless Byron accepted an invitation to support Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire. Byron spent 4,000 pounds of his own money to refit the Greek naval fleet and took personal command of a Greek unit of elite fighters.

Death and Legacy

On February 15, 1824, he fell ill. Doctors bled him, which weakened his condition further and likely gave him an infection.

Byron died on April 19, 1824, at age 36. He was deeply mourned in England and became a hero in Greece. His body was brought back to England, but the clergy refused to bury him at Westminster Abbey, as was the custom for individuals of great stature. Instead, he was buried in the family vault near Newstead. In 1969, a memorial to Byron was finally placed on the floor of Westminster Abbey.

Byron is considered to be the first modern-style celebrity. His image as the personification of the Byronic hero fascinated the public, and his wife Annabella coined the term “Byromania” to refer to the commotion surrounding him. His self-awareness and personal promotion are seen as a beginning to what would become the modern rock star; he would instruct artists painting portraits of him not to paint him with pen or book in hand, but as a “man of action.” While Byron first welcomed fame, he later turned from it by going into voluntary exile from Britain.

Byron exercised a marked influence on Continental literature and art, and his reputation as a poet is higher in many European countries than in Britain or America, although not as high as in his time, when he was widely thought to be the greatest poet in the world. Byron’s writings also inspired many composers. Over forty operas have been based on his works, in addition to three operas about Byron himself (including Virgil Thomson’s Lord Byron). His poetry was set to music by many Romantic composers, including Mendelssohn, Carl Loewe, and Robert Schumann. Among his greatest admirers was Hector Berlioz, whose operas and Mémoires reveal Byron’s influence.