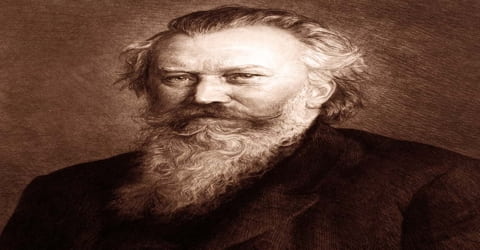

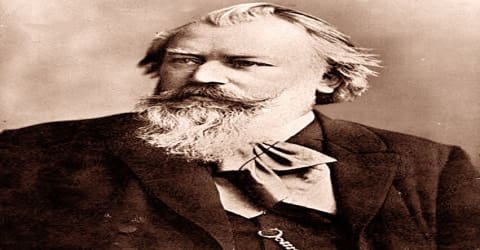

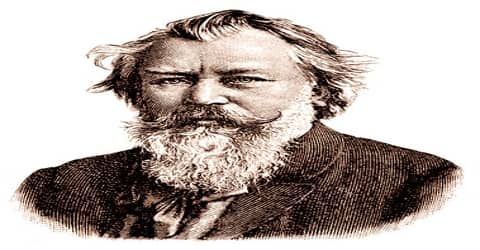

Biography of Johannes Brahms

Johannes Brahms – German composer.

Name: Johannes Brahms

Date of Birth: May 7, 1833

Place of Birth: Hamburg, Germany

Date of Death: April 3, 1897

Place of Death: Vienna, Austria

Occupation: Composer

Father: Johann Jakob Brahms

Mother: Johanna Henrika Christiane Nissen

Early Life

The German composer (writer of music), pianist, and conductor Johannes Brahms was born in Hamburg, Germany, on May 7, 1833, he was the great master of symphonic and sonata style in the second half of the 19th century. Born in Hamburg into a Lutheran family, Brahms spent much of his professional life in Vienna, Austria. His reputation and status as a composer are such that he is sometimes grouped with Johann Sebastian Bach and Ludwig van Beethoven as one of the “Three Bs” of music, a comment originally made by the nineteenth-century conductor Hans von Bülow. His works combine the warm feeling of the Romantic period with the control of classical influences such as Johann Sebastian Bach (1685–1750) and Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827). He was a well-known German composer and pianist best remembered for his choral work ‘A German Requiem.’

Although the experimental musicians like the followers of Liszt and Wagner considered him old fashioned, critics, in general, accorded him the same rank as Bach and Beethoven. In fact, all through his life he had championed the Classical tradition of Joseph Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven and his works combined the warmth of the Romantic era with the restrain of classical music. Born to a struggling musician, he began performing in taverns and dance halls at the age of thirteen. Very soon, he began to write his own music. By the time he was twenty, he was able to catch the attention of many established musicians and music critics.

He composed for symphony orchestra, chamber ensembles, piano, organ, and voice and chorus. A virtuoso pianist, he premiered many of his own works. He worked with some of the leading performers of his time, including the pianist Clara Schumann and the violinist Joseph Joachim (the three were close friends). Many of his works have become staples of the modern concert repertoire. An uncompromising perfectionist, Brahms destroyed some of his works and left others unpublished.

However, the real fame came when Brahms settled in Vienna in the early 1860s and wrote his famous piece ‘A German Requiem’. Brahms was always a perfectionist and rewrote each work several times. In his long career, he had composed varied types of works such as symphonies, concerti, chamber music, piano works, and choral compositions. In addition to that, he had also left more than two hundred songs. Brahms has been considered, by his contemporaries and by later writers, as both a traditionalist and an innovator.

Brahms’s music is firmly rooted in the structures and compositional techniques of the Classical masters. While many contemporaries found his music too academic, his contribution and craftsmanship have been admired by subsequent figures as diverse as Arnold Schoenberg and Edward Elgar. The diligent, highly constructed nature of Brahms’s works was a starting point and an inspiration for a generation of composers. Embedded within his meticulous structures, however, are deeply romantic motifs.

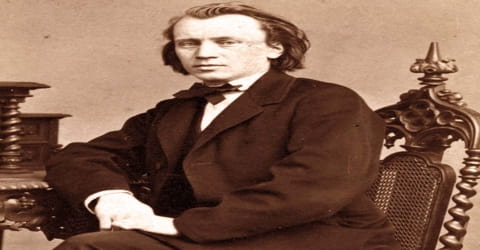

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

One of the most significant German composers of the 19th century, Johannes Brahms was born on 7 May 1833 in Hamburg. His father, Johann Jakob Brahms, was a musician from Heide, who came to Hamburg to pursue a career in music. His mother, Johanna Henrika Christiane Nissen, was a seamstress. He was born the second of their three children. When Brahms was six years old he created his own method of writing music in order to get the melodies he created on paper. At the age of seven, he began studying piano under Otto Cossel. He played a private concert at the age of ten to obtain funds for his future education. Also at ten years old, he began piano lessons with Eduard Marxsen (1806–1887).

Cossel complained in 1842 that Brahms “could be such a good player, but he will not stop his never-ending composing.” At the age of 10, Brahms made his debut as a performer in a private concert including Beethoven’s quintet for piano and winds Op. 16 and a piano quartet by Mozart. He also played as a solo work an étude of Henri Herz. By 1845 he had written a piano sonata in G minor. Brahms’s parents disapproved of his early efforts as a composer, feeling that he had better career prospects as a performer.

When Brahms turned thirteen, Brahms began contributing to the family income by playing at taverns, restaurants and local dance halls in the city’s dock area. Working for a prolonged period in smoke laden rooms soon affected his health and he became ill.

Brahms was offered a chance to take a long rest at Winsen-an-der-Luhe, Germany, where he conducted a small male choir for whom he wrote his first choral compositions. Upon his return to Hamburg he gave several concerts, but after failing to win recognition he continued playing at taverns, giving inexpensive piano lessons, and arranging popular music for piano.

Personal Life

Johannes Brahms did not marry. His personal life was also troubled. In 1859 he became engaged to Agathe von Siebold. The engagement was soon broken off, but even after this Brahms wrote to her: “I love you! I must see you again, but I am incapable of bearing fetters. Please write me … whether … I may come again to clasp you in my arms, to kiss you, and tell you that I love you.” They never saw one another again, and Brahms later confirmed to a friend that Agathe was his “last love”.

(Clara Wieck Schumann)

One reason could be that Clara was fourteen years older than Brahms and had a large family. He was also torn between his regards for Robert and his love for Clara. Yet, Clara remained an important part of his life and when they were not together, they communicated through letters.

Career and Works

In 1850 Johannes Brahms met with the Hungarian violinist Ede Reményi and accompanied him in a number of recitals over the next few years. This was Brahms’s introduction to “gypsy-style” music such as the czardas, which was later to prove the foundation of his most lucrative and popular compositions, the two sets of Hungarian Dances (1869 and 1880). 1850 also marked Brahms’s first contact (albeit a failed one) with Robert Schumann; during Schumann’s visit to Hamburg that year, friends persuaded Brahms to send the former some of his compositions, but the package was returned unopened.

The first turning point came in 1853 when Brahms met the violin virtuoso Joseph Joachim, who instantly realized the talent of Brahms. Joachim, in turn, recommended Brahms to the composer Robert Schumann, and an immediate friendship between the two composers resulted. Schumann wrote enthusiastically about Brahms in the periodical Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, praising his compositions. The article created a sensation. From this moment Brahms was a force in the world of music, though there were always factors that made difficulties for him.

Reményi and Brahms went on several successful concert tours in 1853. They met the German violinist Joseph Joachim (1831–1907), who introduced them to Franz Liszt (1811–1886) at Weimar, Germany. Liszt received them warmly and was greatly impressed with Brahms’s compositions. Liszt hoped to recruit him to join his group of composers, but Brahms declined; he was not really a fan of Liszt’s music. Joachim also wrote a letter praising Brahms to the composer Robert Schumann (1810–1856).

In 1854 Schumann fell ill. In a sign of his close friendship with his mentor and his family, Brahms assisted Schumann’s wife, Clara, with the management of her household affairs. Music historians believe that Brahms soon fell in love with Clara, though she doesn’t seem to have reciprocated his admiration. Even after Schumann’s death in 1856, the two remained solely friends.

Schumann’s accolade led to the first publication of Brahms’s works under his own name. Brahms went to Leipzig where Breitkopf & Härtel published his Opp. 1–4 (the Piano Sonatas Nos. 1 and 2, the Six Songs Op. 3, and the Scherzo Op. 4), whilst Bartholf Senff published the Third Piano Sonata Op. 5 and the Six Songs Op. 6. In Leipzig, he gave recitals including his own first two piano sonatas and met with among others Ferdinand David, Ignaz Moscheles, and Hector Berlioz.

During 1854 Brahms wrote the Piano Trio No. 1, the Variations on a Theme of Schumann for piano, and the Ballades for piano. Also that year Brahms was summoned to Düsseldorf, Germany when Schumann had a breakdown and attempted suicide. To earn his living, he taught piano privately but also spent some time on concert tours. Two concerts given with the singer Julius Stockhausen served to establish Brahms as an important song composer. For the next couple of years, he divided his time between Detmold, Göttingen, and Hamburg, wherein 1859, he formed and conducted a ladies’ choir.

In spite of such a hectic schedule, the period turned out to be highly productive for him. ‘Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor’ (1854–58) and ‘String Sextet in B-flat Major’ (1858–60) are two of his most famous works of this period.

Between 1857 and 1860 Brahms moved between the court of Detmold where he taught the piano and conducted a choral society and Göttingen, while in 1859 he was appointed conductor of a women’s choir in Hamburg. Such posts provided valuable practical experience and left him enough time for his own work. At this point Brahms’s productivity increased, and, apart from the two delightful Serenades for orchestra and the colorful first String Sextet in B-flat Major (1858–60), he also completed his turbulent Piano Concerto No. 1 in D Minor (1854–58).

In autumn 1862 Brahms made his first visit to Vienna, staying there over the winter. There he became an associate of two close members of Wagner’s circle, his earlier friend Peter Cornelius and Karl Tausig, and of Joseph Hellmesberger Sr. and Julius Epstein, respectively the Director and head of violin studies, and the head of piano studies, at the Vienna Conservatoire. Brahms’s circle grew to include the notable critic (an opponent of the ‘New German School’) Eduard Hanslick, the conductor Hermann Levi and the surgeon Theodor Billroth, who were to become amongst his greatest advocates.

Therefore he went back to Vienna in 1863 and assumed the post of the director of Singakademie, a renowned choral society. Soon a conflict arose between his followers and the followers of Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt, who represented the new school of music. Therefore in 1864, Brahms resigned from his post. Initially, he thought of taking up a position elsewhere but later he decided to settle permanently in Vienna and concentrate fully on composing.

Brahms, for the most part, enjoyed steady success in Vienna. By the early 1870s, he was principal conductor of the Society of Friends of Music. He also directed the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra for three seasons. His own work continued as well. In 1868, following the death of his mother, he finished “A German Requiem,” a composition based on Biblical texts and often cited as one of the most important pieces of choral music created in the 19th century. The multi-layered piece brings together mixed chorus, solo voices, and a complete orchestra.

In the year 1866, Brahms’s most important publications were the Variations on a Theme of Paganini for piano, the String Sextet in G Major, and several song collections. It is not always possible to date Brahms’s compositions exactly because of his habit of revising a work or adding to it frequently. Thus, the German Requiem, practically finished in 1866, was not published in its final form until 1869. It was also given its first complete performance that year.

In 1865, Brahms began to compose ‘Eindeutsches Requiem, nach Worten der heiligen Schrift’ (A German Requiem, to Words of the Holy Scriptures), his largest choral work. Premiered in 1868, the work established him as one of the greatest European composers.

Brahms also experienced at this period popular success with works such as his first set of Hungarian Dances (1869), the Liebeslieder Walzer, Op. 52, (1868/69), and his collections of lieder (Opp. 43 and 46–49). Following such successes, he finally completed a number of works that he had wrestled with over many years such as the cantata Rinaldo (1863–1868), his first two string quartets Op. 51 nos. 1 and 2 (1865–1873), the third piano quartet (1855–1875), and most notably his first symphony which appeared in 1876, but which had been begun as early as 1855.

Brahms’s father died in 1872. After a short holiday, Brahms accepted the post of artistic director of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde (Friends of Music) in Vienna. Masterpieces continued to pour from his pen. He composed, went on concert tours chiefly to improve his own music, and took long holidays. He now had plenty of money and could do as he pleased. He resigned as conductor of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in 1875, for even those duties had become a burden to him. That summer he worked on his Symphony No. 1 and sketched the Symphony No. 2.

In 1873 Brahms offered the masterly orchestral version of his Variations on a Theme by Haydn. After this experiment, which even the self-critical Brahms had to consider completely successful, he felt ready to embark on the completion of his Symphony No. 1 in C Minor. This magnificent work was completed in 1876 and first heard in the same year. Now that the composer had proved to himself his full command of the symphonic idiom, within the next year he produced his Symphony No. 2 in D Major (1877). This is a serene and idyllic work, avoiding the heroic pathos of Symphony No. 1. He let six years elapse before his Symphony No. 3 in F Major (1883).

In May 1876, Cambridge University offered to grant honorary degrees of Doctor of Music to both Brahms and Joachim, provided that they composed new pieces as “theses” and was present in Cambridge to receive their degrees. Brahms was averse to traveling to England and requested to receive the degree ‘in absentia’, offering as his thesis the previously performed (November 1876) symphony. But of the two, only Joachim went to England and only he was granted a degree. Brahms “acknowledged the invitation” by giving the manuscript score and parts of his first symphony to Joachim, who led the performance at Cambridge March 8, 1877 (English premiere).

Meanwhile, in 1881, Brahms completed his second piano concerto titled, ‘Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat major’, a work he started in 1878. In the premiere held in Budapest on November 9, 1881, Brahms was the soloist. In the same year, he also tried out his new orchestral works with the Meiningen Court Orchestra.

The University of Breslau (now the University of Wrocław, Poland) conferred an honorary degree on him in 1879. The composer thanked the university by writing the Academic Festival Overture (1881) based on various German student songs. Among his other orchestral works at this time were the Violin Concerto in D Major (1878) and the Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major (1881).

In 1890, Brahms published ‘String Quintet in G Major’ and declared it to be his last work. However, the very next year, he composed ‘Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. 114’ for the clarinetist Richard Mühlfeld. Later in 1894, he also composed two Clarinet Sonatas.

Much of the credit for the worldwide acceptance of Brahms’s orchestral works was due to the activities of their great interpreter, Hans von Bülow, who had transferred his loyalty from the Liszt-Wagner camp to Brahms. Bülow exerted tremendous energy in seeing that Brahms’s compositions received properly executed performances. When he was about sixty years old, Brahms began to age rapidly, and his production decreased sharply. He often spoke of having arrived at the end of his creative activity. Nonetheless, the works of this last period are awesome in their magnificence and concentration, and the last of his published works, the Vier ernste Gesänge (Four Serious Songs), are among the high points of his career, which drew on work from the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. It was a revealing piece for the composer, damning what was found on earth and embracing death as a relief from the material world’s excesses and pain.

In 1891 Brahms was inspired to write chamber music for the clarinet owing to his acquaintance with an outstanding clarinetist, Richard Mühlfeld, whom he had heard perform some months before. With Mühlfeld in mind, Brahms wrote his Trio for Clarinet, Cello, and Piano (1891); the great Quintet for Clarinet and Strings (1891); and two Sonatas for Clarinet and Piano (1894). These works are perfect in structure and beautifully adapted to the potentialities of the wind instrument.

However, it was ‘Eindeutsches Requiem, nach Worten der heiligen Schrift’ (A German Requiem), composed between 1865 and 1868, which confirmed his position as one of the best composers in Europe. The work comprises seven movements and lasts for around 65 to 80 minutes. It is sacred but non-liturgical and as the name suggests, is in the German language.

Death and Legacy

Brahms’s health took a turn for the worse after he heard the news of the death of Clara Schumann in 1896. Around this time, Brahms’ own health began to deteriorate. Doctors discovered that his liver was in poor condition. His last public appearance was on 3 March 1897, when he saw Hans Richter conduct his Symphony No. 4. There was an ovation after each of the four movements. He made the effort, three weeks before his death, to attend the premiere of Johann Strauss’s operetta Die Göttin der Vernunft (The Goddess of Reason) in March 1897.

On April 3, 1897, Johannes Brahms died of cancer of the liver. Brahms is buried in the Zentralfriedhof in Vienna, under a monument designed by Victor Horta and the sculptor Ilse von Twardowski-Conrat.

Shortly after his death, English composer Hubert Parry wrote a short symphonic movement for orchestra called ‘Elegy for Brahms’. Later music critic Max Kalbeck published his biography in eight volumes. His correspondences to various persons, including Clara, have also been published, giving us a glimpse into his life.

Brahms was a master of counterpoint. “For Brahms, … the most complicated forms of counterpoint were a natural means of expressing his emotions,” writes Geiringer. “As Palestrina or Bach succeeded in giving spiritual significance to their technique, so Brahms could turn a canon in motu contrario or a canon per augmentationem into a pure piece of lyrical poetry.” Writers on Brahms have commented on his use of counterpoint. For example, of Op. 9, Variations on a Theme by Robert Schumann, Geiringer writes that Brahms “displays all the resources of contrapuntal art”. In the A Major piano quartet Opus 26, Swafford notes that the third movement is “demonic-canonic”, echoing Haydn’s famous minuet for string quartet called the ‘Witch’s Round’.” Swafford further opines that “thematic development, counterpoint, and form were the dominant technical terms in which Brahms… thought about music”.

Brahms’s music complemented and counteracted the rapid growth of Romantic individualism in the second half of the 19th century. He was a traditionalist in the sense that he greatly revered the subtlety and power of movement displayed by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven, with an added influence from Franz Schubert. The Romantic composers’ preoccupation with the emotional moment had created new harmonic vistas, but it had two inescapable consequences. First, it had produced a tendency toward rhapsody that often resulted in a lack of structure. Second, it had slowed down the processes of music, so that Wagner had been able to discover a means of writing music that moved as slowly as his often-argumentative stage action.

Information Source: