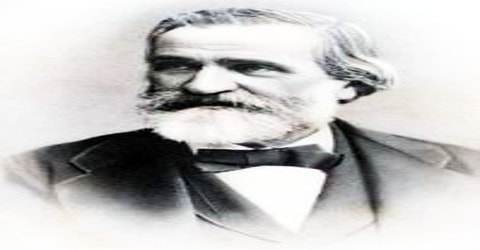

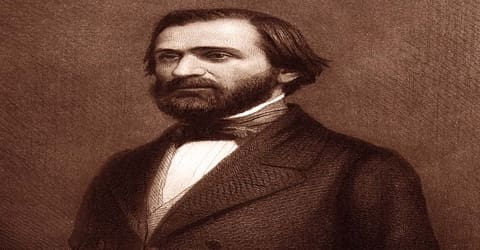

Biography of Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Verdi – Italian opera composer.

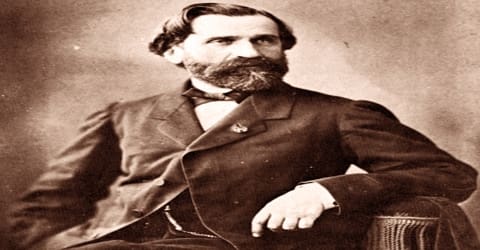

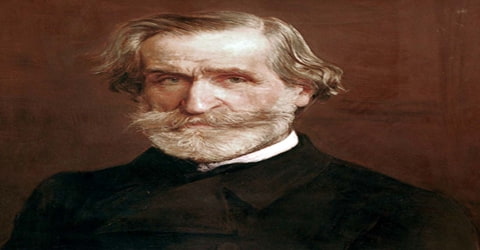

Name: Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi

Date of Birth: October 10, 1813

Place of Birth: Le Roncole, Italy

Date of Death: January 27, 1901

Place of Death: Milan, Italy

Occupation: Composer

Father: Carlo Giuseppe Verdi

Mother: Luigia Uttini

Spouse/Ex: Giuseppina Strepponi (m. 1859–1897), Margherita Barezzi (m. 1836–1840)

Children: Virginia Maria Luigia Verdi, Icilio Romano Verdi

Early Life

An Italian composer who is known for several operas, including La Traviata and Aida, Giuseppe Verdi was born on 10th October 1813, at their home in Le Roncole, a village near Busseto, then in the Département Taro and within the borders of the First French Empire following the annexation of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza. He came to dominate the Italian opera scene after the era of Vincenzo Bellini, Gaetano Donizetti, and Gioachino Rossini, whose works significantly influenced him. By his 30s, he had become one of the pre-eminent opera composers in history.

Giuseppe Verdi’s works reflected the popular culture of his time and they are still adored and revered by musicians all over the world. Being an amazingly talented music enthusiast, his works were noted for the musical luster they embodied. Verdi’s compositions were influenced by great musicians like Gaetano Donizetti, Saverio Mercadante, Rossini, Bellini, and Giacomo Meyerbeer. Lacking any strong schooling in the discipline of music, his achievements were purely out of his strong innate taste for music. Verdi himself had said that “Of all composers, past, and present, I am the least learned.”

Verdi produced many successful operas, including La Traviata, Falstaff, and Aida, and became known for his skill in creating melody and his profound use of the theatrical effect. Additionally, his rejection of the traditional Italian opera for integrated scenes and unified acts earned him fame.

In his early operas, Verdi demonstrated sympathy with the Risorgimento movement which sought the unification of Italy. He also participated briefly as an elected politician. The chorus “Va, pensiero” from his early opera Nabucco (1842), and similar choruses in later operas were much in the spirit of the unification movement, and the composer himself became esteemed as a representative of these ideals. An intensely private person, Verdi, however, did not seek to ingratiate himself with popular movements and as he became professionally successful was able to reduce his operatic workload and sought to establish himself as a landowner in his native region.

Verdi used to be very intimately involved with each and every stage of the creation of his operas and portray his characters quite incisively, which was probably the reason why his plays received immense popularity and appreciation. He enriched the music world with his masterpieces like ‘Requiem’ (1874), ‘Otello’ (1887)’, and ‘Falstaff’ (1893).

Even to this day, his works remain extremely popular, and the bicentenary of his birth in 2013 was celebrated worldwide with several broadcasts and performances.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Giuseppe Verdi, in full Giuseppe Fortunino Francesco Verdi, was born to a family of innkeepers on 9 October 1813, in Le Rancole, a village near Bussetto. His parents were Carlo Giuseppe Verdi and Luigia Uttini. He also had a younger sister, Giuseppa, who passed away at the age of 17 in 1833.

The child must have shown unusual talent, for he was given lessons from his fourth year, a spinet was bought for him, and by age 9 he was standing in for his teacher as organist in the village church. He attended the village school and at 10 the ginnasio (secondary school) in Busseto. When he was ten, but he returned to Bussetto every Sunday to play the organ, by covering several kilometers of distance on foot. When he was 13, he was asked to act as a replacement in the first public event that took place in his home town. He played his own music, and his performance was a great success, earning him much local recognition.

Verdi first developed musical talents at a young age, after moving with his family from Le Roncole to the neighboring town of Busseto. There, he began studying musical composition. In 1832, Verdi applied for admission at the Milan Conservatory but was rejected due to his age. Subsequently, he began studying under Vincenzo Lavigna, a famous composer from Milan.

After completing his studies, he set his sights on Milan, where he was introduced to an amateur choral group, ‘Società Filarmonica’, which was led by Pietro Massini. He attended the Societa frequently. Later, he got an opportunity to function as rehearsal director and continuo player for an opera by Giaochino Rossini, which proved to be the turning point in his career. It was after this, that he wrote his first opera, which was titled ‘Rocester’.

Personal Life

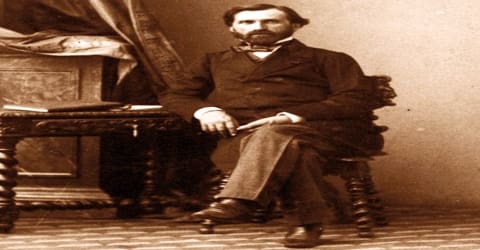

(Margherita Barezzi, Verdi’s first wife)

Verdi married Margherita in May 1836, and by March 1837, she had given birth to their first child, Virginia Maria Luigia on 26 March 1837. Icilio Romano followed on 11 July 1838. Both the children died young, Virginia on 12 August 1838, Ilicio on 22 October 1839.

Several years later, Verdi married Giuseppina Strepponi in 1859, after a long time of cohabitation. She was quite a loving and supportive wife, who supported him in every way possible.

(Giuseppina Strepponi, Verdi’s second wife)

Verdi was similarly never explicit about his religious beliefs. Anti-clerical by nature in his early years, he nonetheless built a chapel at Sant’Agata but is rarely recorded as going to church. Strepponi wrote in 1871 “I won’t say Verdi is an atheist, but he is not much of a believer.” Rosselli comments that in the Requiem “The prospect of Hell appears to rule…the Requiem is troubled to the end,” and offers little consolation.

Career and Works

Giuseppe Verdi got his start in Italy’s music industry in 1833, when he was hired as a conductor at the Philharmonic Society in Busseto. In addition to composing, he made a living as an organist around this time. Three years later, in 1836, Verdi wed Margherita Barezzi, the daughter of a friend, Antonio Barezzi. He was composing his second opera ‘Un giorno di regno’ when his wife passed away at just the age of 26, because of encephalitis. His work was premiered shortly, after but it turned out to be a flop, which led Verdi into a state of depression.

In 1837, the young composer asked for Massini’s assistance to stage his opera in Milan. The La Scala impresario, Bartolomeo Merelli, agreed to put on Oberto (as the reworked opera was now called, with a libretto rewritten by Temistocle Solera) in November 1839. It achieved a respectable 13 additional performances, following which Merelli offered Verdi a contract for three more works.

In 1838, at age 25, Verdi returned to Milan, where he completed his first opera, Oberto, in 1839, with the help of fellow musician Giulio Ricordi; the opera’s debut production was held at La Scala, an opera house in Milan. He followed Oberto with the comic opera Un giorno di regno, which premiered in Milan in September 1840, at Teatro alla Scala. Unlike Oberto, Verdi’s second opera was not well-received by audiences or critics. Making the experience worse for the young musician, Un giorno di regno’s debut was painfully overshadowed by the death of his wife, Margherita, on June 18, 1840, at age 26.

Verdi started composing again, and began to work on the music for ‘Nabucco.’ It was first performed on 9 March 1842, and its success made Verdi a new hero of Italian music. It became so successful and popular that within a decade it reached as far as Petersburg, Russia, and Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Verdi overcame his despair by composing Nabucodonoser (composed 1841, first performed 1842; known as Nabucco), based on the biblical Nebuchadnezzar (Nebuchadrezzar II), though the well-known story he told later about snapping out of his lethargy only when the libretto fell open at the chorus “Va, pensiero” by that time one of his most beloved works—is no longer credited. (The older Verdi embroidered on various aspects of his early life, exaggerating the lowliness of his origins, for example.) Nabucco succeeded as sensationally as Un giorno had failed abjectly, and Verdi at age 28 became the new hero of Italian music. The work sped across Italy and the whole world of opera; within a decade it had reached as far as St. Petersburg and Buenos Aires, Argentina. While its musical style is primitive by the composer’s later standards, Nabucco’s raw energy has kept it alive a century and a half later.

Following the success of ‘Nabucco,’’ he settled in Milan, where he became acquainted with several influential people. Later, he wrote, ‘I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata’, based on an epic poem by Tommasso Grossi. It was dedicated to Margia Luigia, the Habsburg Duchess of Parma, who died shortly after the premier in 1843. He took on Emanuele Muzio, a junior, as his only pupil. Shortly, as he grew close to Verdi, he became indispensable. He used to assist Verdi in preparing scores, transcriptions, and in conducting many of his works in the USA and places outside of Italy.

A period of hard work for Verdi with the creation of twenty operas (excluding revisions and translations) followed over the next sixteen years, culminating in Un ballo in maschera. This period was not without its frustrations and setbacks for the young composer, and he was frequently demoralised. In April 1845, in connection with I due Foscari, he wrote: “I am happy, no matter what reception it gets, and I am utterly indifferent to everything. I cannot wait for these next three years to pass. I have to write six operas, then addio to everything.” In 1858 Verdi complained: “Since Nabucco, you may say, I have never had one hour of peace. Sixteen years in the galleys.”

In the 1840s Verdi drew on Victor Hugo for Ernani, Lord Byron for I due Foscari (1844; The Two Foscari) and Il corsaro (1848; The Corsair), Friedrich von Schiller for Giovanna d’Arco (1845; Joan of Arc), I masnadieri (1847; The Bandits), and Luisa Miller (1849), Voltaire for Alzira (1845), and Zacharias Werner for Attila (1846).

For the rest of the 1840s, and through the 1850s, ’60s, and ’70s, Verdi continued to garner success and fame. Comprising a popular operatic series throughout the decades was Rigoletto (1851), Il trovatore (1853), La traviata (1853), Don Carlos (1867) and Aida, which premiered at the Cairo Opera House in 1871. Four years later, in 1874, Verdi completed Messa da Requiem (best known simply as Requiem), which was meant to be his final composition. He retired shortly thereafter.

Having become an international celebrity, Verdi devoted himself to creating new works for the Opera at Paris, as well as other theatres. ‘Les Vepres siciliennes’ (The Sicilian Nespers, 1855), ‘Simon Boccanegra’ (1857), and ‘Un ballo in Maschera’ (A masked ball, 1857), were three of his most popular works during that time. Later, he wrote ‘Macbeth’ based on Shakespeare’s drama of the same name, which was best known for its originality, and for being independent of tradition.

Verdi went to Naples early in January 1858 to work with Somma on the libretto of the opera Gustave III, which over a year later would become Un ballo in maschera. At the end of 1859, Verdi wrote to his friend Cesare De Sanctis “I have not made any more music, I have not seen any more music, I have not thought any more about music. I don’t even know what color my last opera is, and I almost don’t remember it.” He began to remodel Sant’Agata, which took most of 1860 to complete and on which he continued to work for the next twenty years. This included major work on a square room that became his workroom, his bedroom, and his office.

From 1855 to 1870 Verdi devoted himself to providing works for the Opéra at Paris and other theatres conforming to the Parisian operatic standard, which demanded spectacular dramas on subjects of high seriousness in five acts with a ballet. He was pointedly challenging Giacomo Meyerbeer, the one European composer more renowned and wealthier than he was, on Meyerbeer’s own ground. While these operas show advances in many areas and include superb scenes, none of them is as satisfactory as a whole as any of the three great operas of the early 1850s.

Having achieved some fame and prosperity, Verdi began in 1859 to take an active interest in Italian politics. His early commitment to the Risorgimento movement is difficult to estimate accurately; in the words of the music historian Philip Gossett “myths intensifying and exaggerating such sentiment began circulating” during the nineteenth century. An example is a claim that when the “Va, Pensiero” chorus in Nabucco was first sung in Milan, the audience, responding with nationalistic fervor, demanded an encore. As encores were expressly forbidden by the government at the time, such a gesture would have been extremely significant. But in fact, the piece encored was not “Va, Pensiero” but the hymn “Immenso Jehova”.

In 1862 Verdi represented Italian musicians at the London Exhibition, for which he composed a cantata to words by the up-and-coming poet and composer Arrigo Boito. In opera, the big money came from foreign commissions, and in the same year his next work, La Forza del Destino (The Force of Destiny), was produced at St. Petersburg. Always on the lookout for novel dramatic material, Verdi had wanted to tackle the epic narrative extending over many years and many locations, with scenes of high life and low.

A revival of Macbeth in Paris in 1865 was not a success, but he obtained a commission for a new work, Don Carlos, based on the drama, Don Carlos by Friedrich Schiller. He and Giuseppina spent late 1866 and much of 1867 in Paris, where they heard, and did not warm to, Giacomo Meyerbeer’s last opera L’Africaine, and Richard Wagner’s overture to Tannhäuser. The opera’s premiere in 1867 drew mixed comments. While the critic Théophile Gautier praised the work, the composer Georges Bizet was disappointed at Verdi’s changing style: “Verdi is no longer Italian. He is following Wagner.”

Verdi felt that both operas with foreign commissions required revision for Italian theatres; this he accomplished for Forza in 1869 and Don Carlo (as it is now usually called) in 1884 and 1887. He needed none with the piece in which at last he fashioned a libretto exactly to his needs, Aida. Verdi wrote a detailed scenario much simpler than those of the previous two operas employing Antonio Ghislanzoni, a competent poet, to turn it into verse, the meters of which were often dictated by the composer.

During the 1860s and 1870s, Verdi paid great attention to his estate around Busseto, purchasing additional land, dealing with unsatisfactory (in one case, embezzling) stewards, installing irrigation, and coping with variable harvests and economic slumps. In 1867, both Verdi’s father Carlo, with whom he had restored good relations, and his early patron and father-in-law Antonio Barezzi, died. Verdi and Giuseppina decided to adopt Carlo’s great-niece Filomena Maria Verdi, then seven years old, as their own child. She was to marry in 1878 the son of Verdi’s friend and lawyer Angelo Carrara and her family became eventually the heirs of Verdi’s estate.

Commissioned by the khedive of Egypt to celebrate the opening of Cairo’s new Opera House in 1869 (Verdi had earlier declined a commission for an inaugural hymn celebrating the opening of the Suez Canal), Aida finally premiered there in 1871 and went on to receive worldwide acclaim. Verdi had achieved the grandeur and the gravitas of the Parisian style without its notorious excess padding and without any weak spots, and onto it, he had grafted an emotional intensity that only he could furnish.

Verdi spent much of 1872 and 1873 supervising the Italian productions of Aida at Milan, Parma, and Naples, effectively acting as producer and demanding high standards and adequate rehearsal time. During the rehearsals for the Naples production, he wrote his string quartet, the only chamber music by him to survive, and the only major work in the form by an Italian of the 19th century.

Verdi challenged Giacomo Meyerbeer, a European composer much more renowned and wealthier, whom he surpassed with ‘Don Carlos’ (1884), a work regarded by many as a masterpiece.

Despite his retirement plans, in the mid-1880s, through a connection initiated by longtime friend Giulio Ricordi, Verdi collaborated with composer and novelist Arrigo Boito (also known as Enrico Giuseppe Giovanni Boito) to complete Otello. Completed in 1886, the four-act opera was performed for the first time at Milan’s Teatro Alla Scala on February 5, 1887. Initially meeting with incredible acclaim throughout Europe, the opera based on William Shakespeare’s play Othello continues to be regarded as one of the greatest operas of all time.

After the success of ‘Otello’, Verdi started writing ‘Falstaff.’ It was first premiered on 9 February 1893 at La Scala, in which influential figures including aristocrats and critics from all over Europe were present. The performance, needless to say, was a huge success.

The first performance of Falstaff took place at La Scala on 9 February 1893. For the first night, official ticket prices were thirty times higher than usual. Royalty, aristocracy, critics and leading figures from the arts all over Europe were present. The performance was a huge success; numbers were encored, and at the end, the applause for Verdi and the cast lasted an hour. That was followed by a tumultuous welcome when the composer, his wife, and Boito arrived at the Grand Hotel de Milan. Even more hectic scenes ensued when he went to Rome in May for the opera’s premiere at the Teatro Costanzi when crowds of well-wishers at the railway station initially forced Verdi to take refuge in a tool-shed. He witnessed the performance from the Royal Box at the side of King Umberto and the Queen.

During his last years, Verdi got involved in several philanthropic ventures, which included publishing a song for the welfare of the earthquake victims in Sicily in 1894, as well as building rest houses for retired musicians and hospitals. His last major composition, the choral set of Four sacred pieces, was published in 1898.

Finally, six years later, appeared Falstaff, Verdi’s only comedy apart from the early, ill-fated Un giorno di regno. In this work Roger Parker writes that:

“the listener is bombarded by a stunning diversity of rhythms, orchestral textures, melodic motifs, and harmonic devices. Passages that in earlier times would have furnished material for an entire number here crowd in on each other, shouldering themselves unceremoniously to the fore in bewildering succession”. Rosselli comments:

“In Otello Verdi had miniaturized the forms of romantic Italian opera; in Falstaff, he miniaturized himself…Moments…crystallize a feeling…as though an aria or duet had been precipitated into a phrase.”

Verdi’s operas are full of catchy tunes. Many people would be familiar with some of these tunes, even if they don’t know opera or don’t listen to classical music. He liked Shakespeare, which is why some of his operas, ‘Macbeth’, ‘Otello’, and ‘Falstaff’ are all based on Shakespeare’s plays.

Awards and Honor

Giuseppe Verdi was awarded the Order of Chevalier of the Legion of Honour in 1894.

Death and Legacy

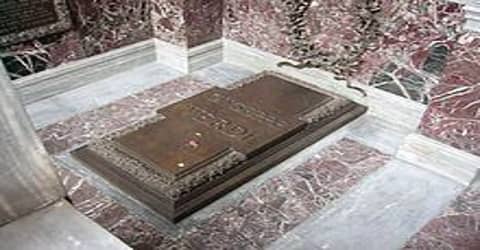

Giuseppe Verdi had a stroke while he was in Milan in early 1901, which led to his death six days later on 27 January 1901 at the age of 87. His funeral was attended by musicians from all over Italy.

Verdi was initially buried in a private ceremony at Milan’s Cimitero Monumentale. A month later, his body was moved to the crypt of the Casa di Riposo. On this occasion, “Va, pensiero” from Nabucco was conducted by Arturo Toscanini with a chorus of 820 singers. A huge crowd was in attendance, estimated at 300,000. Boito wrote to a friend, in words which recall the mysterious final scene of Don Carlos, “Verdi sleeps like a King of Spain in his Escurial, under a bronze slab that completely covers him.”

Verdi appeared on the operatic scene just as the Italian bel canto tradition of Rossini, Vincenzo Bellini, and Donizetti, in the quarter-century from about 1815 to 1845, entered its waning phase. He transformed it and dominated Italian opera alone for another 30 years. It was a period of constant experimentation, constant refinement of musical and dramatic means a process that seems to have continued underground to germinate the two transcendent Shakespeare operas written 20 years after his supposed retirement.

Composing over 25 operas throughout his career, Verdi continues to be regarded today as one of the greatest composers in history. Furthermore, his works have reportedly been performed more than any other performer’s worldwide.

Information Source: