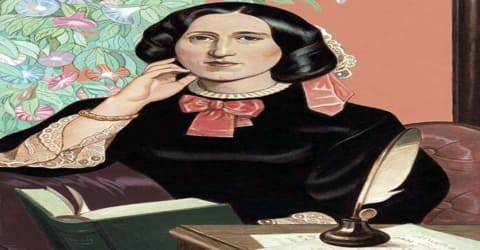

Biography of George Eliot

George Eliot – English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and writer.

Name: Mary Anne Evans

Pen Name: George Eliot

Date of Birth: 22 November 1819

Place of Birth: Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England, United Kingdom

Date of Death: 22 December 1880 (aged 61)

Place of Death: Chelsea, London, England

Occupation: Novelist, poet, journalist, translator

Father: Robert Evans

Mother: Christiana Pearson

Spouse/Ex: John Walter Cross (m. 1880–1880)

Partner: George Henry Lewes (1854–78)

Early Life

George Eliot was the pen name (a writing name) used by the English novelist Mary Ann Evans, was born on 22 November 1819 in Nuneaton, Warwickshire, England. She was an English novelist, poet, journalist, translator, and one of the leading writers of the Victorian era. Her real name was Mary Ann Evans but she used a male pen name, as female authors were believed to be writing only lighthearted novels in those days and she wanted to be taken seriously as well as the break that stereotype. She wrote seven novels, including Adam Bede (1859), The Mill on the Floss (1860), Silas Marner (1861), Romola (1862–63), Middlemarch (1871–72), and Daniel Deronda (1876), most of which are set in provincial England and known for their realism and psychological insight.

Her books were mainly appreciated for their descriptions of rural society, and she believed that there were much interest and importance in the mundane details of ordinary country lives. She is best remembered for ‘Middlemarch’, which was not just her masterpiece, but also one of the greatest novels in the history of English fiction. She worked as a translator as well, which exposed her to various German religious, social and philosophical texts, elements of which shown up in her fiction.

She was not religious, but she held the belief that religious beliefs and tradition maintained social order and morality. Eliot has been placed by literary critic Harold Bloom as one of the greatest writers of the West. Her books have also been adapted into various films and television programs.

Although female authors were published under their own names during her lifetime, she wanted to escape the stereotype of women’s writing being limited to lighthearted romances. She also wanted to have her fiction judged separately from her already extensive and widely known work as an editor and critic. Another factor in her use of a pen name may have been a desire to shield her private life from public scrutiny, thus avoiding the scandal that would have arisen because of her relationship with the married George Henry Lewes.

Her masterpiece, Middlemarch, is not only a major social record but also one of the greatest novels in the history of fiction.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

George Eliot, pseudonym of Mary Ann, or Marian, Cross, née Evans, was born on 22 November 1819, Warwickshire, England. She was the second child of an estate manager Robert Evans and his second wife Christiana. Mary Ann’s name was sometimes shortened to Marian. Her full siblings were Christiana, known as Chrissey (1814–59), Isaac (1816–1890), and twin brothers who died a few days after birth in March 1821. She also had a half-brother, Robert (1802–64), and half-sister, Fanny (1805–82), from her father’s previous marriage to Harriet Poynton (1780–1809). Her father Robert Evans, of Welsh ancestry, was the manager of the Arbury Hall Estate for the Newdigate family in Warwickshire, and Mary Ann was born on the estate at South Farm. In early 1820 the family moved to a house named Griff House, between Nuneaton and Bedworth.

When Eliot was five years old, she and her sister were sent to boarding school at Attleborough, Warwickshire, and when she was nine she was transferred to a boarding school at Nuneaton. It was during these years that Mary discovered her passion for reading. At thirteen years of age, Mary went to school at Coventry. Her education was conservative (one that held with the traditions of the day), dominated by Christian teachings.

She completed her schooling when she was sixteen years old. At Mrs. Wallington’s school, she was taught by the evangelical Maria Lewis to whom her earliest surviving letters are addressed. In the religious atmosphere of Miss Franklin’s school, Evans was exposed to a quiet, disciplined belief opposed to evangelicalism.

After her mother’s death and her brother’s marriage a few years later, she and her father moved to a house near Coventry. Shortly after, she started questioning her religious faith, which led to her father refusing to live with her, which forced her to go and live with her brother. Later, her brother and her friends arranged a reconciliation, and she respectfully attended church till her father’s death in 1849.

Influenced by the so-called Higher Criticism a largely German school that studied the Bible and that attempted to treat sacred writings as human and historical documents she devoted herself to translating these works from the German language to English for the English public. She published her translation of David Strauss’s Life of Jesus in 1846 and her translation of Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach’s Essence of Christianity in 1854.

Five days after her father’s funeral, she traveled to Switzerland with the Brays. She decided to stay on in Geneva alone, living first on the lake at Plongeon (near the present-day United Nations buildings) and then on the second floor of a house owned by her friends François and Juliet d’Albert Durade on the rue de Chanoines (now the rue de la Pelisserie). She commented happily that “one feels in a downy nest high up in a good old tree”. Her stay is commemorated by a plaque on the building. While residing there, she read avidly and took long walks in the beautiful Swiss countryside, which was a great inspiration to her. François Durade painted her portrait there as well.

Personal Life

George Eliot was romantically involved with George Henry Lewes, whom she first met in 1851. Lewes was already married, but since he and his wife were separated for some years, and even his wife was living with another man, they were able to continue their relationship.

In July 1854, Lewes and Evans traveled to Weimar and Berlin together for the purpose of research. Before going to Germany, Evans continued her theological work with a translation of Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity, and while abroad she wrote essays and worked on her translation of Baruch Spinoza’s Ethics, which she completed in 1856, but which was not published in her lifetime.

Though it was not possible for Lewes to divorce his wife and formally get married to Evans, she started calling herself Mary Ann Evans Lewes and referred to Lewes as her husband. Extra-marital affairs were not uncommon at that time in Victorian society, but the public admission of the relationship earned them the moral disapproval of the English society.

On 16 May 1880 Eliot married John Cross and again changed her name, this time to Mary Anne Cross. While the marriage courted some controversy due to the difference in ages, it pleased her brother Isaac, who had broken off relations with her when she had begun to live with Lewes, and now sent congratulations.

Before her relationship with George Lewes, she had several embarrassing, unreciprocated attachments, including one with John Chapman and another one with Herbert Spencer.

Career and Works

On her return to England the following year (1850), she moved to London with the intent of becoming a writer, and she began referring to herself as Marian Evans. She stayed at the house of John Chapman, the radical publisher whom she had met earlier at Rosehill and who had published her Strauss translation. Chapman had recently purchased the campaigning, left-wing journal The Westminster Review, and Evans became its assistant editor in 1851. Though the official editor was John Chapman, it was Eliot who contributed to most of the work.

Here, Evans came into contact with a group known as the positivists. They were followers of the doctrines of the French philosopher (a seeker of knowledge) Auguste Comte (1798–1857), who was interested in applying scientific knowledge to the problems of society. One of these men was George Henry Lewes (1817–1878), a brilliant philosopher, psychologist (one who is educated in the science of the mind), and literary critic, with whom she formed a lasting relationship. As he was separated from his wife but unable to obtain a divorce, their relationship was a scandal in those times. Nevertheless, the obvious devotion and long length of their union came to be respected.

In 1850 Lewes and a friend, the journalist Thornton Leigh Hunt founded a radical weekly called The Leader, for which he wrote the literary and theatrical sections.

Although Chapman was officially the editor, it was Evans who did most of the work of producing the journal, contributing many essays and reviews beginning with the January 1852 issue and continuing until the end of her employment at the Review in the first half of 1854. Eliot sympathized with the 1848 Revolutions throughout continental Europe and even hoped that the Italians would chase the “odious Austrians” out of Lombard and that “decayed monarchs” would be pensioned off, although she believed a gradual reformist approach to social problems was best for England. The philosopher and critic George Henry Lewes (1817–78) met Evans in 1851, and by 1854 they had decided to live together.

In July 1854, after the publication of her translation of Ludwig Feuerbach’s Essence of Christianity, they went to Germany together. In all but the legal form, it was a marriage, and it continued happily until Lewes’s death in 1878. “Women who are content with light and easily broken ties,” she told Mrs. Bray, “do not act as I have done. They obtain what they desire and are still invited to dinner.”

In 1857 she published a short story, “Amos Barton,” and took the pen name “George Eliot” in order to prevent the discrimination (unfair treatment because of gender or race) that women of her era faced. After collecting her short stories in Scenes of Clerical Life (2 vols., 1858), Eliot published her first novel, Adam Bede (1859). The plot was drawn from a memory of Eliot’s aunt, a Methodist preacher, whom she used as a model for a character in the novel.

Not only was it an instant success, but it also triggered a response in the readers as they wanted to know who this George Eliot was, who possessed such a great intellect. Someone even pretended to be the author, which forced the real George Eliot, Mary Ann Evans, to come forward.

Eliot’s next novel, The Mill on the Floss (1860), shows even stronger traces of her childhood and youth in small-town and rural England. The final pages of the novel show the heroine reaching toward a “religion of humanity” (the belief in human beings and their individual moral and intellectual abilities to work toward a better society), which was Eliot’s aim to instill in her readers.

At this time historical novels were in vogue, and during their visit to Florence in 1860 Lewes suggested Girolamo Savonarola as a good subject, George Eliot grasped it enthusiastically and began to plan Romola (1862–63).

In 1861, Eliot published a short novel, Silas Marner, which through use as a school textbook is her best-known work. This work is about a man who has been alone for a long time and who has lost his faith in his fellow man. He learns to trust others again by learning to love a child who he meets through chance, but whom he eventually adopts as his own.

Romola was planned as a serial for Blackwood’s until an offer of £10,000 from The Cornhill Magazine induced George Eliot to desert her old publisher; but rather than divide the book into the 16 installments the editor wanted, she accepted £3,000 less, evidence of artistic integrity few writers would have shown. Details of Florentine history, setting, costume, and dialogue were scrupulously studied at the British Museum and during the second trip to Italy in 1861. It was published in 14 parts between July 1862 and August 1863. Though the book lacks the spontaneity of the English stories, it has been unduly disparaged.

George Eliot’s greatest work ‘Middlemarch’ was started in 1869 and completed in 1871. It was first published in eight monthly installments in ‘Blackwood’s Magazine’. It is for this novel that she is remembered as the ‘The Victorian Sage’, which definitely was a remarkable achievement for a woman in nineteenth-century Britain.

When the American Civil War broke out, Eliot expressed sympathy with the North, which was a rare stance in England at the time. In 1868 she supported Richard Congreve’s protests against Britain’s imperial policy toward Ireland and her view of the growing movement in support of Irish Home Rule was positive.

Eliot aimed at creating confidence in her readers by her honesty in describing human beings. In her next novel, Felix Holt (1866), she came as close as she ever did to setting up her fiction in order to convey her beliefs. In this work, however, it is not her moral but her political thought that is expressed as she addressed the social questions that were then disturbing England. The hero of the novel is a young reformer who carries Eliot’s message to the working class. This message is that they could get themselves out of their miserable circumstances much more effectively by expecting more of themselves both morally and intellectually and not just through reform of the government or through union activities. In contrast to Holt, the conservative politician is shown to be part of the corrupt political process and a person who is dishonest with the working class people that he represents. The heroine of the novel supports this political lesson by choosing the genuine, but poor, reformer rather than the opportunist (a person who takes advantage of any situations for personal gain with no regard for right or wrong) of her own class.

Her realism led her to create characters neither good nor evil, and characters that were loosely drawn. She usually let the reader make judgments about her characters and their motivations instead of letting the characters reveal themselves on their own.

She was influenced by the writings of John Stuart Mill and read all of his major works as they were published. In Mill’s Subjection of Women (1869) she judged the second chapter excoriating the laws which oppress married women “excellent.” She was supportive of Mill’s parliamentary run but believed that the electorate was unlikely to vote for a philosopher and was surprised when he won. While Mill served in parliament, she expressed her agreement with Mill’s efforts on behalf of female suffrage, being “inclined to hope for much good from the serious presentation of women’s claims before Parliament.”

Eliot did not publish any novels for some years after Felix Holt, and it might have appeared that her creative thread was gone. After traveling in Spain in 1867, she produced a dramatic poem, The Spanish Gipsy, in the following year, but neither this poem nor the other poems of the period are as good as her nonpoetic writing.

‘Middlemarch’, which is considered to be her best work, was first published in eight installments during 1871-1872. This novel pours light on several important themes such as the status of women, the nature of marriage, idealism, political reform, hypocrisy, self-interest, and religion. Evans started writing the two pieces that eventually formed ‘Middlemarch’ in the years 1869-1870. She completed the first one in 1871. Initially, the reviews were mixed but now it is regarded as one of the greatest novels ever written in English.

Every class of Middlemarch society is depicted from the landed gentry and clergy to the manufacturers and professional men, the shopkeepers, publicans, farmers, and laborers. Several strands of the plot are interwoven to reinforce each other by contrast and parallel. Yet the story depends not on close-knit intrigue but on showing the incalculably diffusive effect of the unhistoric acts of those who “lived faithfully a hidden life and rest in unvisited tombs.”

Her last novel was Daniel Deronda, published in 1876, after which she and Lewes moved to Witley, Surrey. By this time Lewes’s health was failing, and he died two years later, on 30 November 1878. Eliot spent the next two years editing Lewes’s final work, ‘Life and Mind’, for publication, and found solace and companionship with John Walter Cross, a Scottish commission agent 20 years her junior, whose mother had recently died.

Working as a translator, Eliot was exposed to German texts of religious, social, and moral philosophy such as Friedrich Strauss’s Life of Jesus, Feuerbach’s The Essence of Christianity, and Spinoza’s Ethics. Elements from these works show up in her fiction, much of which is written with her trademark sense of agnostic humanism. She had taken particular notice of Feuerbach’s conception of Christianity, positing that our understanding of the nature of the divine was to be found ultimately in the nature of humanity projected onto a divine figure.

Awards and Honor

(Blue plaque, Holly Lodge, 31 Wimbledon Park Road, London)

Eliot’s book ‘Middlemarch’, which was her best work, is regarded today was one of the best novels in English literature.

Several landmarks in her birthplace of Nuneaton are named in her honor. These include The George Eliot School, Middlemarch Junior School, George Eliot Hospital, (formerly Nuneaton Emergency Hospital), and George Eliot Road, in Foleshill, Coventry.

A statue of Eliot is in Newdegate Street, Nuneaton, and Nuneaton Museum & Art Gallery has a display of artifacts related to her.

Death and Legacy

A few months after her second marriage, Evans fell ill with a throat infection, which combined with the kidney diseases she had been having for years, led to her death on 22 December 1880. She was 61.

Eliot was not buried in Westminster Abbey because of her denial of the Christian faith and her adulterous affair with Lewes. She was buried in Highgate Cemetery (East), Highgate, London, in the area reserved for societal outcasts, religious dissenters and agnostics, besides the love of her life, George Henry Lewes. The graves of Karl Marx and her friend Herbert Spencer are nearby. In 1980, on the centenary of her death, a memorial stone was established for her in the Poets’ Corner.

George Eliot’s first novel ‘Adam Bede’ was described by her as a country story ‘full of breath of cows and the scent of hay’. The book was not only rich in humor but was also popular because of its masterly realism. It was a combination of deep human sympathy and rigorous moral judgment. Her last novel ‘Daniel Deronda’, which was written in eight parts, was built on the contrast between a poor girl and an upper class one. The keen analysis of the characters in this novel by Evans is appreciated by her critics.

In the 20th century, she was championed by a new breed of critics, most notably by Virginia Woolf, who called Middlemarch “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people”. In 1994, literary critic Harold Bloom placed Eliot among the most important Western writers of all time. In a 2007 authors’ poll by TIME, Middlemarch was voted the tenth greatest literary work ever written. In 2015, writers from outside the UK voted it first among all British novels “by a landslide”. The various film and television adaptations of Eliot’s books have re-introduced her to the wider reading public.

Information Source: