Biography of Emily Dickinson

Emily Dickinson – American poet.

Name: Emily Elizabeth Dickinson

Date of Birth: December 10, 1830

Place of Birth: Amherst, Massachusetts, US

Date of Death: May 15, 1886 (aged 55)

Place of Death: Amherst, Massachusetts, US

Father: Edward Dickinson

Mother: Emily Norcross Dickinson

Occupation: Poet

Early Life

Emily Dickinson was a reclusive American poet. Unrecognized in her own time, Dickinson is known posthumously for her innovative use of form and syntax. She was born in Amherst, Massachusetts into a prominent family with strong ties to its community. After studying at the Amherst Academy for seven years in her youth, she briefly attended the Mount Holyoke Female Seminary before returning to her family’s house in Amherst.

Born on December 10, 1830, in Amherst, Massachusetts, Emily Dickinson left school as a teenager, eventually living a reclusive life on the family homestead. There, she secretly created bundles of poetry and wrote hundreds of letters. Due to a discovery by sister Lavinia, Dickinson’s remarkable work was published after her death on May 15, 1886, in Amherst and she is now considered one of the towering figures of American literature.

Dickinson lived much of her life in reclusive isolation. Considered an eccentric by locals, she developed a noted penchant for white clothing and became known for her reluctance to greet guests or, later in life, to even leave her bedroom. Dickinson never married, and most friendships between her and others depended entirely upon correspondence. She was a recluse for the later years of her life.

Only 10 of Emily Dickinson’s nearly 1,800 poems are known to have been published in her lifetime. Devoted to private pursuits, she sent hundreds of poems to friends and correspondents while apparently keeping the greater number to herself. She habitually worked in verse forms suggestive of hymns and ballads, with lines of three or four stresses. Her unusual off-rhymes have been seen as both experimental and influenced by the 18th-century hymnist Isaac Watts. She freely ignored the usual rules of versification and even of grammar, and in the intellectual content of her work she likewise proved exceptionally bold and original. Her verse is distinguished by its epigrammatic compression, haunting personal voice, enigmatic brilliance, and lack of high polish.

Although Dickinson’s acquaintances were most likely aware of her writing, it was not until after her death in 1886 when Lavinia, Dickinson’s younger sister, discovered her cache of poems that the breadth of her work became apparent to the public. Her first collection of poetry was published in 1890 by personal acquaintances Thomas Wentworth Higginson and Mabel Loomis Todd, though both heavily edited the content. A complete, and mostly unaltered, collection of her poetry became available for the first time when scholar Thomas H. Johnson published The Poems of Emily Dickinson in 1955.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Emily Dickinson, in full Emily Elizabeth Dickinson, was born December 10, 1830, Amherst, Massachusetts, U.S. She was the oldest daughter of Edward Dickinson, a successful lawyer, member of Congress, and for many years treasurer of Amherst College, and of Emily Norcross Dickinson, a timid woman. Emily Dickinson’s paternal grandfather, Samuel Dickinson, was one of the founders of Amherst College. In 1813, he built the Homestead, a large mansion on the town’s Main Street that became the focus of Dickinson family life for the better part of a century. Samuel Dickinson’s eldest son, Edward, was treasurer of Amherst College for nearly forty years, served numerous terms as a State Legislator, and represented the Hampshire district in the United States Congress. He married Emily Norcross in 1828 and the couple had three children: William Austin, Lavinia Norcross, and middle child Emily.

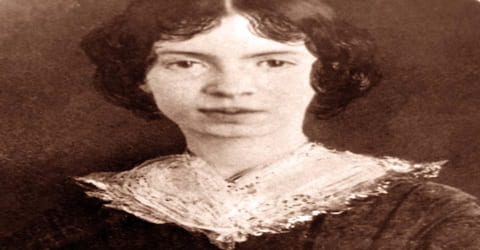

(The Dickinson children (Emily on the left), ca. 1840)

Emily was fun-loving as a child, very smart, and enjoyed the company of others. Her brother, Austin, became a lawyer like his father and was also treasurer of Amherst College. The youngest child of the family, Lavinia, became the chief housekeeper and, like her sister Emily, remained at home all her life and never married. The sixth member of this tightly knit group was Susan Gilbert, Emily’s ambitious and witty schoolmate who married Austin in 1856 and who moved into the house next door to the Dickinsons. At first, she was Emily’s very close friend and a valued critic of her poetry, but by 1879 Emily was speaking of her as a “pseudo-sister” (false sister) and had long since stopped exchanging notes and poems.

An excellent student, Emily Dickinson was educated at Amherst Academy (now Amherst College) for seven years and then attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary for a year. Though the precise reasons for Dickinson’s final departure from the academy in 1848 are unknown; theories offered say that her fragile emotional state may have played a role and/or that her father decided to pull her from the school. Dickinson ultimately never joined a particular church or denomination, steadfastly going against the religious norms of the time.

Dickinson spent seven years at the Academy, taking classes in English and classical literature, Latin, botany, geology, history, “mental philosophy,” and arithmetic. Daniel Taggart Fiske, the school’s principal at the time, would later recall that Dickinson was “very bright” and “an excellent scholar, of exemplary deportment, faithful in all school duties”. Although she had a few terms off due to illness the longest of which was in 1845–1846, when she was enrolled for only eleven weeks she enjoyed her strenuous studies, writing to a friend that the Academy was “a very fine school”.

Dickinson was not religious and probably did not like some elements of the town concerts were rare, and card games, dancing, and theater were unheard of. For relaxation, she walked the hills with her dog, visited friends, and read. Dickinson graduated from Amherst Academy in 1847. The following year (the longest time she was ever to spend away from home) she attended Mount Holyoke Female Seminary, but because of her fragile health, she did not return. At the age of seventeen, she settled into the Dickinson home and turned herself into a housekeeper and a more than ordinary observer of Amherst life.

Personal Life

In 1862 Dickinson turned to the literary critic Thomas Wentworth Higginson for advice about her poems. In time he became, in her words, her “safest friend.” She began her first letter to him by asking, “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my verse is alive?” Six years later she was bold enough to say, “You were not aware that you saved my life.” They did not meet until 1870 at her request, surprisingly and only once more after that.

What Dickinson was seeking was assurance as well as advice, and Higginson apparently gave it without knowing it, through the letters they sent to each other the rest of her life. He helped her not at all with what mattered most to her establishing her own private poetic method but he was a friendly ear and mentor during the most troubled years of her life. Out of her inner troubles came rare poems in a form that Higginson never really understood.

Career and Works

In early 1850, Dickinson wrote that “Amherst is alive with fun this winter … Oh, a very great town this is!” Her high spirits soon turned to melancholy after another death. The Amherst Academy principal, Leonard Humphrey, died suddenly of “brain congestion” at age 25. Two years after his death, she revealed to her friend Abiah Root the extent of her depression:

some of my friends are gone, and some of my friends are sleeping – sleeping the churchyard sleep – the hour of evening is sad – it was once my study hour – my master has gone to rest, and the open leaf of the book, and the scholar at school alone, make the tears come, and I cannot brush them away; I would not if I could, for they are the only tribute I can pay the departed Humphrey.

Until Dickinson was in her mid-20s, her writing mostly took the form of letters, and a surprising number of those that she wrote from age 11 onward have been preserved. Sent to her brother, Austin, or to friends of her own sex, especially Abiah Root, Jane Humphrey, and Susan Gilbert (who would marry Austin), these generous communications overflow with humor, anecdote, invention, and sombre reflection. In general, Dickinson seems to have given and demanded more from her correspondents than she received. On occasion, she interpreted her correspondents’ laxity in replying as evidence of neglect or even betrayal. Indeed, the loss of friends, whether through death or cooling interest, became a basic pattern for Dickinson. Much of her writing, both poetic and epistolary, seems premised on a feeling of abandonment and a matching effort to deny, overcome, or reflect on a sense of solitude.

Dickinson began writing as a teenager. Her early influences include Leonard Humphrey, principal of Amherst Academy, and a family friend named Benjamin Franklin Newton, who sent Dickinson a book of poetry by Ralph Waldo Emerson. In 1855, Dickinson ventured outside of Amherst, as far as Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There, she befriended a minister named Charles Wadsworth, who would also become a cherished correspondent.

From the mid-1850s, Emily’s mother became effectively bedridden with various chronic illnesses until her death in 1882. Writing to a friend in summer 1858, Emily said that she would visit if she could leave “home, or mother. I do not go out at all, lest father will come and miss me, or miss some little act, which I might forget, should I run away – Mother is much as usual. I Know not what to hope of her”. As her mother continued to decline, Dickinson’s domestic responsibilities weighed more heavily upon her and she confined herself within the Homestead. Forty years later, Lavinia stated that because their mother was chronically ill, one of the daughters had to remain always with her. Emily took this role as her own, and “finding the life with her books and nature so congenial, continued to live it”.

Between 1858 and 1866 Dickinson wrote more than eleven hundred poems, full of off-rhymes and odd grammar. Few poems are more than sixteen lines long. The major subjects are love and separation, death, nature, and God but especially love. When she writes “My life closed twice before its close,” one can only guess who her real or imagined lovers might have been. Higginson was not one of them. It is more than likely that her first “dear friend” was Benjamin Newton, a young man too poor to marry who had worked for a few years in her father’s law office.

During a visit to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, in 1855, Dickinson met the Reverend Charles Wadsworth. Sixteen years older than her, a brilliant preacher, and already married, he was hardly more than a mental image of a lover. There is no doubt she made him this, but nothing more. He visited her once in 1860. When he moved to San Francisco, California, in May 1862, she was in despair. Only a month before, Samuel Bowles had sailed for Europe for health reasons. She needed love, but she had to satisfy this need through her poems, perhaps because she felt she could deal with it no other way.

In 1856, Gilbert married Dickinson’s brother, William. The Dickinson family lived on a large home known as the Homestead in Amherst. After their marriage, William and Susan settled in a property next to the Homestead known as the Evergreens. Emily and sister Lavinia served as chief caregivers for their ailing mother until she passed away in 1882. Neither Emily nor her sister ever married and lived together at the Homestead until their respective deaths.

In the late 1850s, the Dickinsons befriended Samuel Bowles, the owner, and editor-in-chief of the Springfield Republican, and his wife, Mary. They visited the Dickinsons regularly for years to come. During this time Emily sent him over three dozen letters and nearly fifty poems. Their friendship brought out some of her most intense writing and Bowles published a few of her poems in his journal. It was from 1858 to 1861 that Dickinson is believed to have written a trio of letters that have been called “The Master Letters”. These three letters, drafted to an unknown man simply referred to as “Master”, continue to be the subject of speculation and contention amongst scholars.

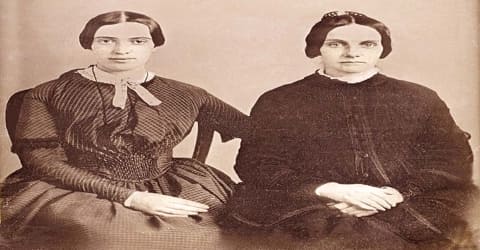

(Emily Dickinson and her friend Kate Scott Turner (ca. 1859))

Dickinson was also treated for a painful ailment of her eyes. After the mid-1860s, she rarely left the confines of the Homestead. It was also around this time, from the late 1850s to mid-’60s, that Dickinson was most productive as a poet, creating small bundles of verse known as fascicles without any awareness on the part of her family members.

In her spare time, Dickinson studied botany and produced a vast herbarium. She also maintained correspondence with a variety of contacts. One of her friendships, with Judge Otis Phillips Lord, seems to have developed into a romance before Lord’s death in 1884.

On June 16, 1874, while in Boston, Edward Dickinson suffered a stroke and died. When the simple funeral was held in the Homestead’s entrance hall, Emily stayed in her room with the door cracked open. Neither did she attend the memorial service on June 28. She wrote to Higginson that her father’s “Heart was pure and terrible and I think no other like it exists.” A year later, on June 15, 1875, Emily’s mother also suffered a stroke, which produced a partial lateral paralysis and impaired memory. Lamenting her mother’s increasing physical as well as mental demands, Emily wrote that “Home is so far from Home”.

After her mother died in 1882, Dickinson summed up the relationship in a confidential letter to her Norcross cousins: “We were never intimate Mother and Children while she was our Mother but…when she became our Child, the Affection came.” The deaths of Dickinson’s friends in her last years Bowles in 1878, Wadsworth in 1882, Lord in 1884, and Jackson in 1885 left her feeling terminally alone. But the single most shattering death, occurring in 1883, was that of her eight-year-old nephew next door, the gifted and charming Gilbert Dickinson.

It is clear that Dickinson could not have written to please publishers, who were not ready to risk her striking style and originality. Had she published during her lifetime, negative public criticism might have driven her to an even more solitary state of existence, even to silence. “If fame belonged to me,” she told Higginson, “I could not escape her; if she did not, the longest day would pass me on the chase.… My barefoot rank is better.” The twentieth century lifted her without doubt to the first rank among poets.

Editions – The standard edition of the poems is the three-volume variorum edition, The Poems of Emily Dickinson: Variorum Edition (1998), edited by R.W. Franklin. He also edited a two-volume work, The Manuscript Books of Emily Dickinson (1981), which provides facsimiles of the poems in their original groupings. The Gorgeous Nothings (2013), edited by Marta L. Werner and Jen Bervin, presents facsimiles of Dickinson’s so-called envelope poems, written on irregularly shaped scraps of paper. The Letters of Emily Dickinson, in three volumes edited by Thomas H. Johnson and Theodora Ward (1958), was reissued in one volume in 1986, and it is still the standard source for the poet’s letters. Open Me Carefully: Emily Dickinson’s Intimate Letters to Susan Huntington Dickinson (1998), edited by Ellen Louise Hart and Martha Nell Smith, is a selection of the poet’s correspondence with her sister-in-law. Facsimiles of the letters to “Master” and Otis Phillips Lord are presented in The Master Letters of Emily Dickinson (1986), edited by R.W. Franklin, and Emily Dickinson’s Open Folios: Scenes of Reading, Surfaces of Writing (1995), edited by Marta L. Werner. Emily Dickinson’s Reception in the 1890s: A Documentary History (1989), edited by Willis J. Buckingham, reprints all known reviews from the first decade of publication. Amherst College and Harvard University make their Dickinson manuscripts available online.

Awards and Honor

Dickinson is taught in American literature and poetry classes in the United States from middle school to college. Several schools have been established in her name; for example, Emily Dickinson Elementary Schools exist in Bozeman, Montana, Redmond, Washington, and New York City.

Dickinson was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1973. A one-woman play titled The Belle of Amherst first appeared on Broadway in 1976, winning several awards; it was later adapted for television.

Death and Legacy

Emily Dickinson died of kidney disease in Amherst, Massachusetts, on May 15, 1886, at the age of 55. She was laid to rest in her family plot at West Cemetery. The Homestead, where Dickinson was born, is now a museum. Austin wrote in his diary that “the day was awful … she ceased to breathe that terrible breathing just before the afternoon whistle sounded for six.”

Dickinson was buried, laid in a white coffin with vanilla-scented heliotrope, a Lady’s Slipper orchid, and a “knot of blue field violets” placed about it. The funeral service, held in the Homestead’s library, was simple and short; Higginson, who had met her only twice, read “No Coward Soul Is Mine”, a poem by Emily Brontë that had been a favorite of Dickinson’s. At Dickinson’s request, her “coffin was not driven but carried through fields of buttercups” for burial in the family plot at West Cemetery on Triangle Street.

Emily Dickinson’s stature as a writer soared from the first publication of her poems in their intended form. She is known for her poignant and compressed verse, which profoundly influenced the direction of 20th-century poetry. The strength of her literary voice, as well as her reclusive and eccentric life, contributes to the sense of Dickinson as an indelible American character who continues to be discussed today.

Information Source: