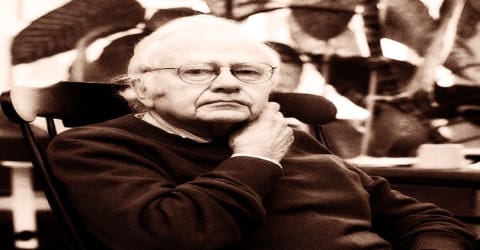

Biography of David H. Hubel

David H. Hubel – Canadian American neurophysiologist.

Name: David Hunter Hubel

Date of Birth: February 27, 1926

Place of Birth: Windsor, Ontario, Canada

Date of Death: September 22, 2013 (aged 87)

Place of Death: Lincoln, Massachusetts, United States

Occupation: Neurophysiologist.

Father: Jesse Hunter Hubel

Mother: Elsie M. Hunter Hubel

Spouse/Ex: Ruth Izzard (m. 1953)

Children: Carl, Eric, and Paul

Early Life

A Canadian American neurobiologist, corecipient with Torsten Nils Wiesel and Roger Wolcott Sperry of the 1981 Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine, David H. Hubel was born on February 27, 1926, in Windsor, Ontario, Canada, to American parents. His grandfather emigrated as a child to the United States from the Bavarian town of Nördlingen. All three scientists were honored for their investigations of brain function, with Hubel and Wiesel sharing half of the award for their collaborative discoveries concerning information processing in the visual system. For much of his career, Hubel was the John Franklin Enders University Professor of Neurobiology at Harvard Medical School. In 1978, Hubel and Wiesel were awarded the Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize from Columbia University.

Born in Canada to American parents, Hubel later became a naturalized American citizen and served the US Army for around three years. He was assigned to the Neurophysiology Division of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research as part of his military service. There he began working on the primary visual cortex of cats, both in sleeping and wakeful condition and invented the tungsten microelectrode. On completion of the military service, he joined Wilmer Institute and worked under Stephen Kuffler. There he collaborated with Torsten Wiesel to work on the relationship between the retina and the visual cortex. The partnership lasted for more than two decades. Meanwhile, they shifted to Harvard University, where they continued with their research, which earned the duo the coveted Nobel Prize. They later worked with kittens to throw light on cataract and defect in alignment in children’s eyes. He was also a successful academician and authored many distinguished books on the visual system.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

David H. Hubel, in full David Hunter Hubel, was born on February 27, 1926, in Windsor, Ontario, Canada into a well-to-do family of Bavarian ancestry. However, both his parents were born and brought up in Detroit, USA. So, David, their only child, was Canadian by birth and American through his parents. David’s paternal grandfather migrated to the USA from Bavaria and made money by inventing the first procedure for producing gelatin pill capsules on a mass scale. His father, Jesse Hunter Hubel, was a chemical engineer, who at the time of David’s birth, was employed at the Windsor Salt Company. David’s mother, Elsie M. Hunter Hubel, had a keen interest in electronics. However, she never studied the subject and lived with that regret. She compensated that by allowing David to pursue his line of interest.

In 1929, his family moved to Montreal, where Hubel spent his formative years. His father was a chemical engineer and Hubel developed a keen interest in science right from childhood, making many experiments in chemistry and electronics. From age six to eighteen, he attended Strathcona Academy in Outremont, Quebec about which he said, “I owe much to the excellent teachers there, especially to Julia Bradshaw, a dedicated, vivacious history teacher with a memorable Irish temper, who awakened me to the possibility of learning how to write readable English.”

David H. Hubel passed out from school in 1943 and then enrolled at the University of McGill with honors in Mathematics and Physics, receiving his B.S. degree in 1947. He liked the experience there because it involved solving problems; there was not much to learn by heart. Subsequently, he enrolled at Medical School at the McGill University. Because he did not learn biology at school, he had a tough time there; but liked biochemistry. By the second year, he also grew an interest in the brain. From then onwards, he spent the summer holidays at Montreal Neurological Institute and worked in the laboratory of neurologist Herbert Jasper. Here he became fascinated with the nervous system. Later, he also began to enjoy clinical medicine. Hubel received his M.D. in 1951 and then did one year of internship at McGill. It was followed by one year of neurology residency at Montreal Neurological Institute and then for one year, he worked with Jasper on clinical electroencephalography (EEG) under a fellowship.

Personal Life

David H. Hubel married Ruth Izzard in 1953; she died on February 17, 2013. For the first two years of their married life, Hubel did not have any income and it was Ruth, who stood by her struggling husband and provided all the necessary support. The couple had three sons; Carl, Eric and Paul and four grandchildren. David and Ruth remained married until her death in 2013.

Career and Works

In 1954, David H. Hubel moved to the United States of America and joined Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine as an assistant resident in neurology. In 1955, before he could establish himself, he was drafted in the United States Army. Fortunately, he was assigned to the Neurophysiology Division of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research as part of his military service. Here he received the mentorship of Michelangelo Fuortes and also had the first opportunity to do research on his own.

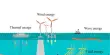

There, Hubel began recording from the primary visual cortex of sleeping and awake cats. At WRAIR, he invented the modern metal microelectrode out of Stoner-Mudge lacquer and tungsten, and the modern hydraulic microdrive, which he had to learn basic machinist skills to produce. He first began to work on the spinal cord, which prepared him for his later works on neurophysiology.

However, his main project was to compare the spontaneous firing of single cortical cells in sleeping and waking cats. To record the electrical impulses of the nerve cells, he first invented the tungsten microelectrode, which took him one year. He then placed it in the visual cortex area of the brain and went on to record sleeping as well as freely moving cats. Subsequently, he found that neuronal activity depended upon the level of arousal. From the reaction of his subjects during wakeful hours, Hubel also realized that it was possible to study how the brain operates during the visual process.

In 1958, Hubel moved to Johns Hopkins and began his collaborations with Wiesel, and discovered orientation selectivity and columnar organization in visual cortex. One year later, he joined the faculty of Harvard University. He first joined the laboratory of Vernon Mountcastle. But, as the laboratory was undergoing renovation at that time, he was invited by Stephen Kuffler to join him at his laboratory at Wilmer Institute, also at Johns Hopkins. At Kuffler’s laboratory, Huber met Torsten Wiesel. Under Kuffler’s direction, the two scientists began to work on the relationship between the retina and the visual cortex. Very soon, they formed a team, which lasted for twenty-two years. Kuffler remained their lifelong friend and also the toughest critic.

Hubel held positions at the Montreal Neurological Institute, Johns Hopkins Hospital (where his association with Wiesel began), and the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research before joining the faculty of Harvard Medical School, along with Wiesel, in 1959. They began collaborating on research that same year. One of their outstanding achievements was the analysis of the flow of nerve impulses from the retina to the sensory and motor centers of the brain. Using tiny electrodes, they tracked the electrical discharges that occur in individual nerve fibers and brain cells as the retina responds to light and the patterns of information are processed and passed along to the brain.

In 1962, they published the result of the above-mentioned experiment. In it, they described various classes of visual neurons and their columnar organization. They also showed that neurons within one column preferred similar orientations and that cortical neurons had ocular dominance and received input from each eye. When in 1964, the Department of Neurobiology was officially established at Harvard University, Kuffler became its Chairman and by the following year, Hubel was appointed as the Professor of Physiology at the same department.

Hubel and Wiesel received the Nobel Prize for two major contributions: firstly, their work on development of the visual system, which involved a description of ocular dominance columns in the 1960s and 1970s; and secondly, their work establishing a foundation for visual neurophysiology, describing how signals from the eye are processed by visual parcels in the neocortex to generate edge detectors, motion detectors, stereoscopic depth detectors, and color detectors, building blocks of the visual scene. By depriving kittens of using one eye, they showed that columns in the primary visual cortex receiving inputs from the other eye took over the areas that would normally receive input from the deprived eye. This has important implications for the understanding of deprivation amblyopia, a type of visual loss due to unilateral visual deprivation during the so-called critical period. These kittens also did not develop areas receiving input from both eyes, a feature needed for binocular vision. Hubel and Wiesel’s experiments showed that ocular dominance develops irreversibly early in childhood development. These studies opened the door for the understanding and treatment of childhood cataracts and strabismus. They were also important in the study of cortical plasticity.

In 1965 Hubel became a professor of physiology and, in 1968, George Packer Berry Professor of Neurobiology. All along, he and Wiesel carried on research work first with cats and then with monkeys. Meanwhile, they had started working on ocular dominance columns, which are stripes of neurons in the visual cortex. They first discovered it in cats; later they used kittens to perform the experiments and found that these columns were severely disrupted when one eye was kept shut for two months. They also found that the neuronal connections were largely present before the eyes were opened and that their organization deteriorated if the subject was deprived of visual input during a critical period after birth. These findings had a great impact on the treatment of cataract or disorder of alignment in children.

Hubel cowrote (with Wiesel) Brain Mechanisms of Vision (1979) and Brain and Visual Perception: The Story of 25-Year Collaboration (2004). His other works include The Visual Cortex of the Brain (1963), The Brain (1984; with Francis Crick), and Eye, Brain, and Vision (1988). Hubel and Wiesel were also awarded (with Vernon Mountcastle of Johns Hopkins) the 1978 Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize for their research on discerning the structural and functional elements of the visual cortex. Hubel was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society (ForMemRS) in 1982.

Awards and Honor

In 1969, David H. Hubel and Wiesel co-received the Dickson Prize, awarded by Carnegie Mellon University, for their work on neurophysiology of vision.

In 1978, the Hubel-Weisel duo received Louisa Gross Horwitz Prize for Biology or Biochemistry from Columbia University for their outstanding contribution in basic research in the fields of biology or biochemistry.

In 1981, the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine was shared between David Hunter Hubel, Torsten Nils Wiesel, and Roger Wolcott Sperry. Hubel and Wiesel received the honor “for their discoveries concerning information processing in the visual system”. While they shared half the prize money the other half went to Sperry.

In 1982, Hubel was elected as a Foreign Member of Royal Society. Then from 1988 to 1989, he was elected as the president of the Society for Neuroscience.

Death and Legacy

David Hunter Hubel died in Lincoln, Massachusetts from kidney failure on September 22, 2013, at the age of 87.

Hubel is best remembered for his work on the nerve impulses, which flow from the retina to the sensory and motor centers in the brain. By implanting tiny electrodes in the brain of anesthetic cats he, along with Wiesel, proved that specific nerve cells are responsible for specific types of visual comprehension. Hubel had also authored a number of books. Moreover, he co-wrote ‘Brain Mechanisms of Vision’ (1979) and ‘Brain and Visual Perception: The Story of a 25-Year Collaboration’ (2004) with Torsten Wiesel and ‘The Brain’ (1984) with Francis Crick.

Information Source: