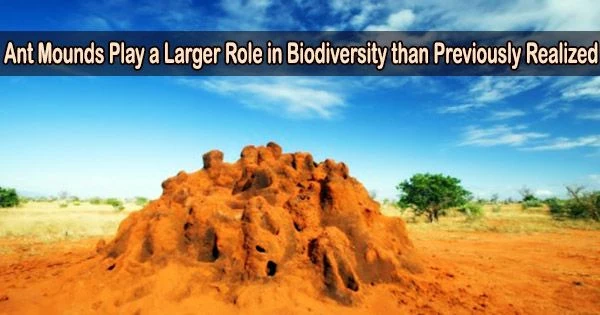

Ants in our gardens annoy most of us. There are so many of them. If you leave food out on your outdoor table for even a few minutes, it will be crawling with ants when you return.

As a result, most gardeners would go to great lengths to eliminate ant colonies in their yard. But perhaps we should leave the ants be? According to a new study published in Arthropod-Plant Interactions, they are extremely beneficial to biodiversity.

With colleagues from the Department of Ecoscience at Aarhus University, Rikke Reisner Hansen has studied ant mounds on Danish heathlands to discover their importance for other insects and for plants.

“The ants drag dead animals back to the ant mound, and this adds carbon and other important nutrients to the surrounding soil. The ant mound moreover warms up the surrounding ground, and in springtime, adders, lizards and beetles like to rest near ant mounds for warmth. The heat and the nutrients create unique conditions that allow certain plant species that don’t otherwise thrive on heathland to thrive on the ant mound,” she says.

Digging on the heath

Hansen went to the heath with a spade to investigate the significance of ant mounds in heathland biodiversity. She looked for two types of ant mound:

Those belonging to the narrow-headed ant, which resemble ant mounds found in Danish forests. Instead of pine needles, narrow-headed ants eat heather and grass leaves. And mounds belonging to the yellow meadow ant. This is a small ant that builds its nest from mineral soil on heathlands.

Whenever she came upon an ant mound, she dug a deep hole directly next to it with her shovel. She could investigate how the ant mound influenced the soil, roots, and fauna both above and below the mound in this way. She also took temperature readings on top of the ant mound and inspected the soil surrounding and beneath it to evaluate soil nutrients.

“It appears that the top part of the ant mound acts like a kind of miniature Costa del Sol for insects and reptiles. The animals exploit the excess heat from the ants for warmth in early spring and on chilly mornings,” she explains, and continues:

“The same applies to plants. If a plant grows on an ant mound, it will blossom or come into leaf faster than the same species growing in the surrounding heathland soil. This is a huge benefit for insects that feed on pollen and nectar, because the ant mounds introduce an extra flowering season.”

The ants drag dead animals back to the ant mound, and this adds carbon and other important nutrients to the surrounding soil. The ant mound moreover warms up the surrounding ground, and in springtime, adders, lizards and beetles like to rest near ant mounds for warmth. The heat and the nutrients create unique conditions that allow certain plant species that don’t otherwise thrive on heathland to thrive on the ant mound.

Rikke Reisner Hansen

The butterfly that fooled an entire colony

The Alcon blue is a butterfly that lives only on the heathland where ants live. The Alcon blue caterpillar has devised a strategy for fooling the ants into thinking it is their queen.

“The Alcon blue lays its eggs on the rare marsh gentian plant. The caterpillar feeds on marsh gentian seeds during the first three stages of its life. When it has grown big enough, it falls to the ground and begins to emit a smell and a sound identical to those of a queen ant larva,” says Hansen, and continues:

“When the worker ants discover what they mistakenly believe is a queen larva, they drag it into the ant nest. They feed the caterpillar, and sometimes they even forget their own offspring, and the colony dies.”

The caterpillar spends the winter in the ant mound before spreading its gorgeous blue wings and leaving the ant mound in the spring. Denmark is home to 12 species of gossamer-winged butterflies, which include the Alcon blue butterfly. Eleven of these species survive best in areas populated with ants. And a handful of these depend on ants to complete their life cycle.

But the ant mounds are also important for other species. Protecting ant mounds can therefore be an important step in mitigating the biodiversity crisis.

Important for biodiversity

The world, including Denmark, is in the middle of a biodiversity crisis. We are losing species at an ever-faster rate as we destroy important habitats when we fell forests, cultivate heathlands or drain bogs.

A total of 1,844 species of animal, plant and fungi are under threat of extinction in Denmark alone. Among these is the Alcon blue. In just 40 years, the Alcon blue has lost more than 15 percent of its habitat in Denmark. This could be because of the way we manage our heathlands, Hansen explains.

“We tend to manage our heathlands as a homogenous landscape. We often apply the same management method throughout a heathland to preserve it as an open landscape. For example, we allow too many animals to graze the land. Or we use large machines to cut the vegetation. Unfortunately, this destroys the ant mounds.”

“To ensure many different plants and animals on the heath, we need to rewild the landscape, or at least return it to the way it was before machinery took over from traditional management systems,” she explains.

A changing landscape

The majority of Denmark was covered in forest until humans began to alter and farm the land. A lightning strike to a tree could spark a large forest fire. Such fires may clear enormous sections of land, and from the charred tree stumps and ashes emerged and grew an open heathland landscape.

Slowly, over the course of decades, trees grew up again and eventually the forest returned. In this way, heathlands emerged and disappeared again over time throughout Denmark.

Because of the changing terrain, the heathlands provided a variety of habitats and were teaming with life and an abundance of species.

According to Hansen, this is the type of heathland landscape that must be restored in Denmark today if we want to do biodiversity good.

“We have to preserve the ant mounds and not use the same management method throughout the heath. Grazing and burning are important management techniques. But we have to apply methods varyingly and adjust them. If we allow goats, sheep or horses to graze on the same, restricted area throughout the summer, they will eat everything and leave a very homogeneous landscape,” she says and explains further:

“It’s all about creating a varied landscape. If you apply a varied management system, the result will be a varied landscape.”

Leave the ant mounds be

In many places in Denmark, the local government is responsible for maintaining and managing the heathland landscapes. Therefore, since local governments often decide the vegetation management plans, maybe they should consider what Hansen has found out?

“Local governments have many skilled biologists in their workforce. They know it’s important to apply varied heathland management techniques. Unfortunately, it is often a matter of finances, and biodiversity is on the losing end,” she says.

Local governments, however, are not the only ones who should take Hansen’s advice. Gardeners must also modify their tactics. At home, in her own garden, Hansen has been experimenting. She has left the ant mounds be. And this has led to much more life, she explains.

“After I left the ant mounds be and sowed wild, indigenous pea flowers, I now have many more common blue butterflies in my garden. It’s teeming with beautiful, blue butterflies,” she says.

She argues that simply planting a few meadow flowers here and there will not increase biodiversity. It is critical to consider the living circumstances required for the butterfly to complete its whole life cycle. Many insects need a variety of landscape types.

“For example, bees need areas with bare, solid soil. Small, warm spots where they can make nests. Other insects need small mounds of earth, water or deadwood. It’s also important to have plants that provide different types of nectar. Some bees can only use the nectar from a single or a few species of flower, and some butterflies only live on certain plants. It’s important that we ensure these small habitat variations in our gardens, both in terms of space and across the year, if we want to give diversity back to nature,” she concludes.