The first farmers planted their roots around 10,000 years ago, both literally and metaphorically. Agriculture enabled hunter-gatherers to build permanent dwellings, which eventually morphed into complex societies in many parts of the world, and it allowed for (theoretically) stable food supplies. However, how that transition occurred is a hotly debated topic. According to a new study, our path to domesticity alternated between periods of sedentary life and a roaming hunter-gatherer lifestyle. What is the proof? The presence (or lack thereof) of the common house mouse.

Southwest Asian hunter-gatherer groups may have begun keeping and caring for animals nearly 13,000 years ago — roughly 2,000 years earlier than previously thought.

Researchers report in PLOS One on September 14 that ancient plant samples extracted from modern-day Syria show hints of charred dung, indicating that people were burning animal droppings by the end of the Old Stone Age. The findings indicate that humans were using dung as fuel and may have begun animal husbandry during or even before the transition to agriculture. However, the exact nature of the animal-human relationship and which animals produced the dung remain unknown.

“We know today that dung fuel is a valuable resource, but it hasn’t really been documented prior to the Neolithic,” says Alexia Smith, an archaeobotanist at the University of Connecticut in Storrs.

We know today that dung fuel is a valuable resource, but it hasn’t really been documented prior to the Neolithic. The spherulite evidence reported here confirms that dung of some sort was used as fuel.

Alexia Smith

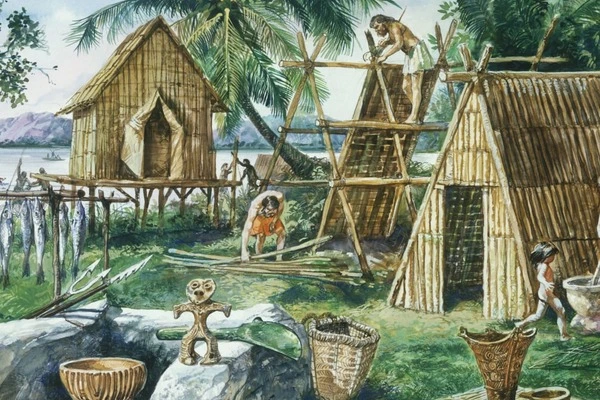

Smith and her colleagues reexamined 43 plant samples collected in the 1970s from a residential dwelling at Abu Hureyra, an archaeological site now submerged beneath the Tabqa Dam reservoir. The samples range in age from 13,300 to 7,800 years, spanning the transition from hunter-gatherer societies to farming and herding.

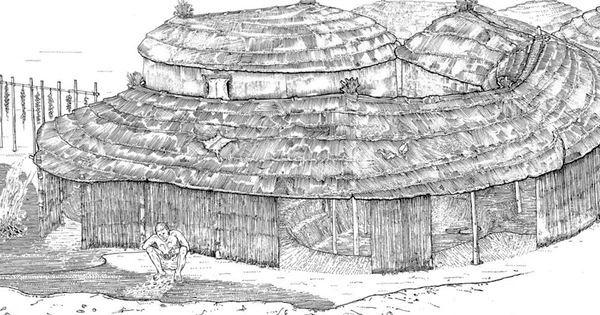

The team then cross-referenced these findings against previously published data from Abu Hureyra. It found that the dung burning coincided with a shift from circular to linear buildings, an indication of a more sedentary lifestyle, along with steadily rising numbers of wild sheep at the site and a decline in gazelle and other small game. Combined, the authors argue, these findings suggest humans may have started tending animals outside their homes and were burning the piles of dung at hand as a supplement to wood.

“The spherulite evidence reported here confirms that dung of some sort was used as fuel,” says Naomi Miller, an archaeobotanist at the University of Pennsylvania who was not involved with the study.

Figuring out what animal left the dung could reveal whether animals were tethered outside or not. While the authors propose wild sheep, which would have been more accommodating to capture, Miller suggests the source was probably roaming wild gazelle.

“Spherulites coming from off-site collection of gazelle dung, stored until burned as fuel, is to my mind a more plausible interpretation,” Miller says. Even if kept for a few days, she says, sheep wouldn’t produce large amounts of dung.

“The whole thing is a classic whodunit,” says anthropologist Melinda Zeder, something perhaps DNA analysis could solve. Gazelle might be the source, she says, and if captured young, the animals may have even been tended for a while — even if they weren’t eventually domesticated.

“The interesting thing is that people [were] experimenting with their environment,” says Zeder, of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. “Domestication is almost incidental to that.”