Africa is slowly but steadily dividing. One of the world’s greatest rifts runs through the continent’s east. Scientists know remarkably little about the complicated movement of this peculiar deformity, despite its massive size. Researchers utilized GPS data and computer models in a recent study to modify that.

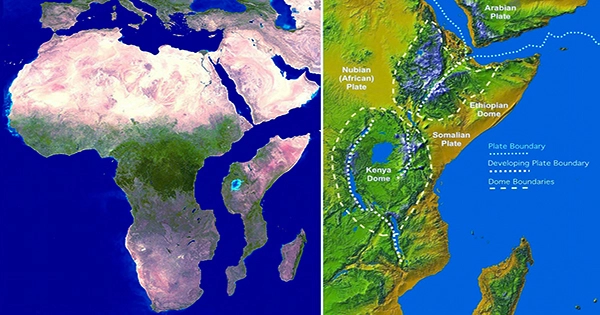

The East African Rift System (EARS) is an active continental rift zone that runs for thousands of kilometers from north to south through Ethiopia, Kenya, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, Zambia, Tanzania, Malawi, and Mozambique.

The EARS is a break in the African plate that has the potential to split the continent into two plates: the smaller Somalian plate and the larger Nubian plate.

The two sides are moving apart at a snail’s pace of millimeters each year, which is less than the rate your fingernails grow. At this rate, the probable break-up will take millions and millions of years.

Having said that, we are already seeing the effects of the EARS because it is seismically active. Giant fractures in the ground can emerge where the lithosphere is strained exceptionally thin, and earthquakes are commonly triggered.

When we stand on the surface of the Earth, it might feel rock solid. When viewed from afar over a long time span, it acts much more like Silly Putty.

“If you hit Silly Putty with a hammer, it can actually crack and break,” D. Sarah Stamps, associate professor in Virginia Tech’s Department of Geosciences, noted in a statement. “However, the Silly Putty stretches as you slowly pull it apart.” As a result, the Earth’s lithosphere acts differently at different time scales.”

There are two major theories about how the EARS travels. The first idea, it is explained by lithospheric buoyancy forces, which are relatively shallow forces related mostly to the rift system’s surface and fluctuations in the density of the lithosphere. The second theory is based on far deeper pressures, specifically how the Earth’s mantle flows horizontally deep beneath East Africa.

Stamps and her colleagues have researched the EARS using computer modeling and GPS satellite data to monitor the surface movement with millimeter precision.

Their findings indicate that EARS is influenced by both shallow lithosphere and deeper mantle forces but in very different ways.

Lithospheric buoyancy forces contribute to the rift extending from east to west, perpendicular to the fracture direction.

The African Superplume, a structure deep under southwest Africa that brings a torrent of mantle material from the core-mantle boundary, is also working on the fracture in a parallel direction – north to south. It runs northeast across the continent, becoming shallower as it moves northward.

In other words, part of the movement driving the vertical fracture across East Africa is the movement of mantle material deep beneath the surface northward, while it is being split open from east to west by forces within the lithosphere.

“We believe that the mantle flow is not driving the east-west, rift-perpendicular direction of some of the deformations, but rather that it is causing the anomalous northward deformation parallel to the rift.” “We confirmed previous ideas that lithospheric buoyancy forces are driving the rift, but we’re bringing new insight that anomalous deformation can happen in East Africa,” Tahiry Rajaonarison, a postdoctoral researcher at New Mexico Tech, noted.