According to research, some First Nations communities, particularly in certain regions, may be more vulnerable to severe influenza illnesses. The specific research findings and danger level can also differ depending on the place and time period analyzed. As a result, for a thorough understanding of the influenza risk among First Nations communities in specific places, it is critical to study the most recent studies and statistics.

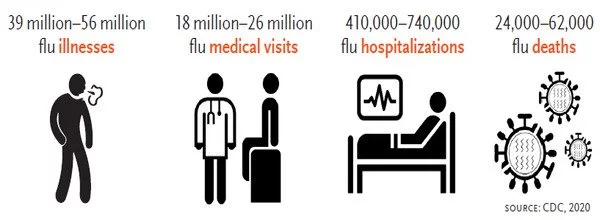

According to new research, First Nations peoples are substantially more likely than non-Indigenous peoples to be hospitalized and die from influenza. Every year, influenza causes approximately 5 million infections and 100,000 fatalities, making it one of the most difficult public health challenges for populations worldwide, particularly First Nations communities.

According to new research from the Peter Doherty Institute for Infection and Immunity (Doherty Institute), First Nations groups around the world are substantially more likely than non-Indigenous populations to be hospitalized and die from influenza.

Our research highlights the widespread and ongoing effects of colonization on the health outcomes of First Nations communities. The majority of solutions to these health gaps are found outside of the health sector, in policies that address the many social determinants of health, such as poverty, housing, education, and racism.

Dr Juliana Betts

The Doherty Institute examined 36 studies that looked at influenza hospitalizations and deaths in First Nations and non-First Nations populations around the world, and discovered that hospitalization and mortality rates in First Nations communities were consistently higher than in corresponding benchmark populations.

First Nations people were more than five times more likely than the general population to be hospitalized with the flu in Canada, New Zealand, and Australia. The authors of the study remark that data on the prevalence of severe flu in First Nations people from poor and middle-income nations is limited.

Dr Katherine Gibney, senior author of the study and Epidemiologist at the Doherty Institute, Royal Melbourne Hospital, stated that additional research is needed to assess the disease burden among First Nations populations in Australia and around the world.

“It is critical that governments ensure that people who have the flu have equitable access to healthcare and that vaccination rates are as high as possible,” Dr Gibney said.

“When we plan for seasonal flu, but especially pandemic flu, we need specific and targeted plans for First Nations people developed by First Nations people.” During COVID, Australia did an excellent job of establishing First Nations-led programs that functioned successfully. And if that can be applied to the flu, it will be extremely beneficial.”

Dr. Gibney went on to say that monitoring respiratory virus information is critical for illness management. “When we receive information about flu hospitalizations and deaths, we need to capture that individual’s First Nations status to see if the gap we’ve described is closing over time, and to continue to advocate for resources to reduce disease burden in First Nations populations.”

Dr Juliana Betts of Monash University, a co-author of the paper, stated that the findings also demonstrates the need for institutional and political transformation.

“Our research highlights the widespread and ongoing effects of colonisation on the health outcomes of First Nations communities,” stated Dr Betts. “The majority of solutions to these health gaps are found outside of the health sector, in policies that address the many social determinants of health, such as poverty, housing, education, and racism.”