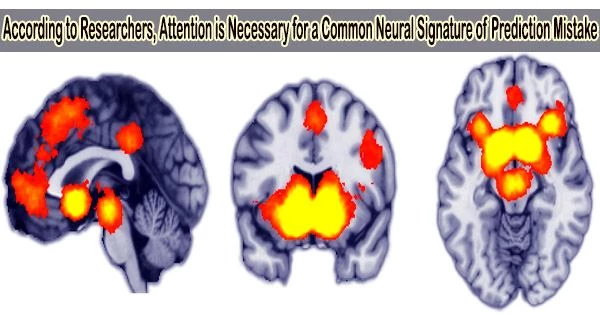

Researchers from the University of California, Irvine have found that additional neural indicators may be able to detect small visual anomalies, and that a neural marker of error detection in the brain’s visual system that was previously thought to be pre-attentive may really require attention.

Research findings were published in June in PLOS Biology in a new study titled, “Attention is required for canonical brain signature of prediction error despite early encoding of the stimuli.”

“According to predictive coding theory, a popular theory for how the brain efficiently processes its immediate sensory surroundings, extra processing is reserved for irregularities in sensory input that are signposted by prediction errors,” said Alie G. Male, Ph.D., co-author and assistant project scientist in the Department of Psychiatry & Human Behavior at the UCI School of Medicine.

Consider a person’s brain as a car engine, and prediction mistakes as a check engine light that alerts to a problem. The check engine light is essential for starting the investigation procedure to fix the problem.

“There are, however, an increasing number of studies that failed to show the well-known neural marker of prediction error in the brain’s visual system,” Male said. “Because of this, it is problematic for those exploring atypical early visual processing indexed by absent or impaired prediction error signaling,” she explained.

“For example, if the well-known neural marker of prediction error is not found in a patient sample, one might falsely conclude aberrant early sensory processing, namely failed irregularity detection when, in truth, the absence could be explained by the need for unmet experimental conditions, such as attention,” Male said.

We find that the well-known neural marker of prediction error in the brain’s visual system does not occur for unattended, subtle, visual irregularities, despite evidence that their corresponding regularities are indeed encoded, although such irregularities may be indexed by an earlier electrophysiological signal at the primary visual cortices.

Alie G. Male

To use the earlier check engine light analogy to explain an unmet condition, it would be similar to failing to notice the check engine light before the engine overheats and concluding that the sensors aren’t functioning when, in fact, the overheating was indicated by another error signal, such as the temperature gauge, and the check engine light only comes on after the car has been in drive for more than 10 minutes.

“This study aims to qualify the electrophysiology of typical early sensory processing without attention, allowing others to later qualify the electrophysiology of atypical early sensory processing without attention,” Male explained.

“We find that the well-known neural marker of prediction error in the brain’s visual system does not occur for unattended, subtle, visual irregularities, despite evidence that their corresponding regularities are indeed encoded, although such irregularities may be indexed by an earlier electrophysiological signal at the primary visual cortices,” she said.

In addition to this result, their research demonstrated that electrophysiology may be used to both encode and detect minor visual regularities. A more reliable model of early visual processing in the visual cortex will be offered by future research on the conditions required for both indexes of error signaling.

Male’s research was motivated by the frustrations of colleagues and peers with whom she discussed the difficulty in obtaining a reliable signal of the well-known neural correlate of prediction error signaling in the visual system, she said.

They came to the conclusion that even in the absence of a signal, encoding data could support the claim that the known neural correlation may not be the exclusive gauge of irregularity signaling.

“We intend to further qualify the conditions needed for showing the well-known neural marker of error detection so that other researchers can adopt optimal parameters in their own irregularity detection research,” she said.

Male co-authored this research with Robert P. O’Shea, from the Discipline of Psychology at the College of Science, Health, Engineering and Education at Murdoch University in Perth, Australia.