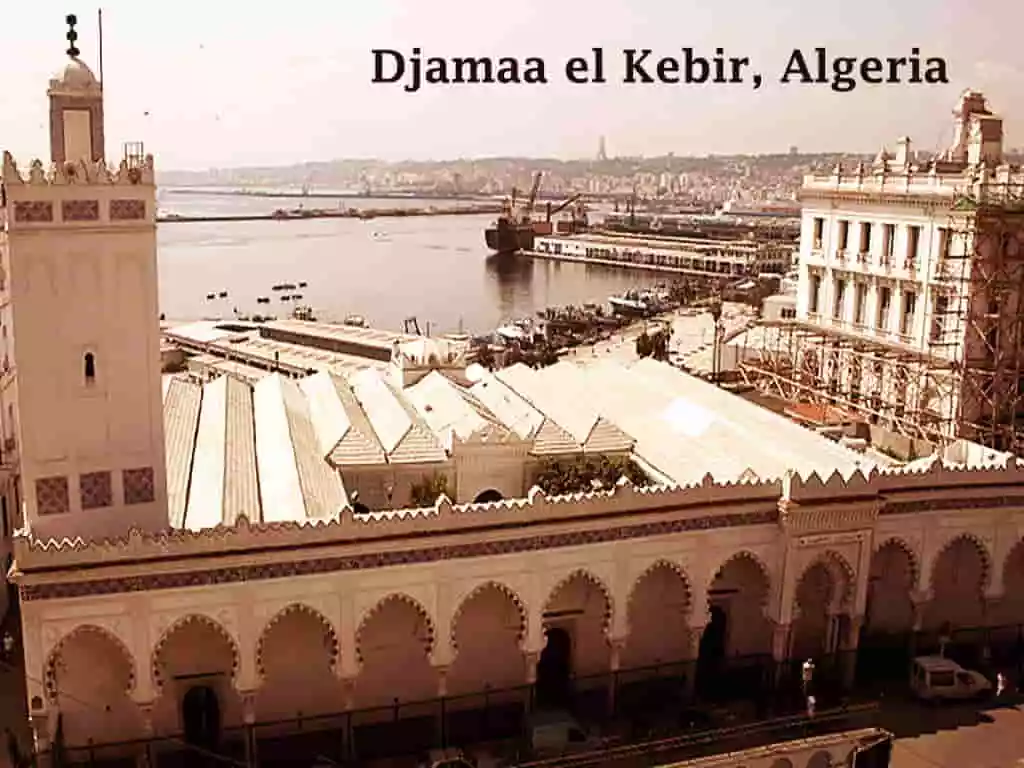

The Great Mosque of Algiers (French: Grande mosquée d’Alger), also known as Djamaa el Kebir (Arabic: الجامع الكبير, romanized: djama’ el-kebir), is one of North Africa’s most important Islamic structures. It is a medieval mosque in Algiers, Algeria, situated within the Casbah (ancient city) and close to the city’s harbor. The Great Mosque of Algiers, with its perpendicular naves to the qibla wall and rectangular courtyard bounded on both narrower sides by a riwaq (gallery), was destined to become a model of religious architecture, notably in the al-Aqsa Maghreb. Although it has undergone additional expansions and restorations since its foundation in 1097, this mosque is one of the rare intact specimens of Almoravid architecture. After Sidi Okba Mosque and Sidi Ghanem Mosque, it is the oldest mosque in Algiers and one of the oldest mosques in Algeria. Previously, during French colonial administration in Algeria, the mosque was located on the Rue de la Marine in Algiers, which served as the entrance to the Algiers Harbor. The mosque, which was built at the start of the colonial period, has a reordered portico of columns and poly-lobed arches. As a result of roadway realignment in the region, these come before the mosque’s façade. During the French invasion of Algiers in 1682 and 1683, the mosque was badly damaged, necessitating the repair of its mihrab and qibla (southern) wall. It was constructed during the reign of Sultan Ali ibn Yusuf. The Ziyyanid Sultan of Tlemcen erected the minaret in 1332 (1324 according to some accounts). The gallery on the mosque’s exterior was erected around 1840. It was built as a result of the French completing a comprehensive rebuild of the street.

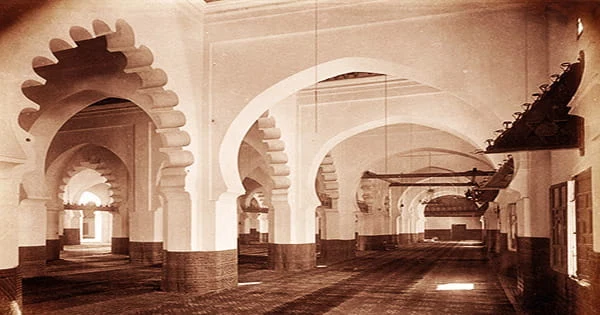

The mosque’s floor plan is rectangular, measuring 46 meters wide by 38 meters deep. Stone, brick, roofing tiles, and wood were utilized to construct the mosque, while ceramics and wood embellishments were used. The rectangular layout of the main body of the structure makes it wider than it is deep. Stone, brick, roofing tiles, and wood were utilized to construct the mosque, while ceramics and wood embellishments were used. The minaret, which was built later, rises from the northwest corner. Bab al-Djenina, with its different offices dedicated for the iman, is located in the northeastern corner; the structure faces a courtyard, across which one can approach the galleries and ultimately the prayer hall. On a 9×11 grid, the mosque features a rectangular courtyard measuring 3846 meters. The rectangle’s narrow sides (width greater than perpendicular depth) feature a riwaq (gallery). Many religious constructions, such as Algeria’s al-Aqsa Maghreb mosque, have adopted this design. The prayer hall is divided into 11 balatat (naves) by pillars and semi-circular arches made of lime-washed stone, each with a double sloping roof. The mihrab, which was built as an integral part of the mosque in 1097, was destroyed by French bombardment in the 17th century. The reconstructed mihrab takes the shape of indented lobed arches at the end of the middle and a much wider nave, which was a common design in 18th-century Algiers. It has a modest fresco façade flanked on either side by two tiny spiral columns with an ogive stucco arch visible in relief. The mihrab is housed in a nook with a level surface. Because of the re-alignment of streets, a portico of columns and poly-lobed arches built at the start of the colonial period precedes the mosque’s façade. According to an inscription on its base, the minaret was built in AH 732 / AD 1332. Significant improvements in the façade became an essential supplementary element following the realignment of Rue de la Marine’s main roadway, as seen presently in the form of “A portico of columns and poly-lobed arches.” The Bab al-Jenina, along with the minaret, is located in another area of the mosque, in the north-east corner, and is intended for the exclusive use of the mosque’s imam. It has a number of rooms that are used on a regular basis. The Almoravid period minbar is sculpted in wood and mounted on wheels for free movement. It’s worth noting that the three Almoravid mosques in the center Maghreb didn’t have minarets at first. The fact that the Almoravids kept the minaret of the Kairouan mosque in Fez during its rebuilding dispels the notion that the minaret was deemed a bid’a (innovation) by the Almoravids.