A lightning strike can generate phosphorus material, but the conditions for this to happen are extremely rare. When lightning strikes, it can heat the surrounding air to temperatures of up to 30,000 kelvin, which is hotter than the surface of the sun. This extreme heat can cause chemical reactions in the air and on the ground below.

A lightning strike in New Port Richey, Florida, triggered a chemical reaction that resulted in the formation of a new material that is intermediate between space minerals and minerals found on Earth. Lightning and other high-energy events can produce unusual chemical reactions. In this case, the end result is a new material that is intermediate between space minerals and minerals found on Earth.

A University of South Florida professor discovered the formation of a new phosphorus material after lightning struck a tree in a New Port Richey neighborhood. It was discovered in a rock for the first time in solid form on Earth and may represent a new mineral group.

“We have never seen this material occur naturally on Earth – minerals similar to it can be found in meteorites and space, but we’ve never seen this exact material anywhere,” said geoscientist Matthew Pasek.

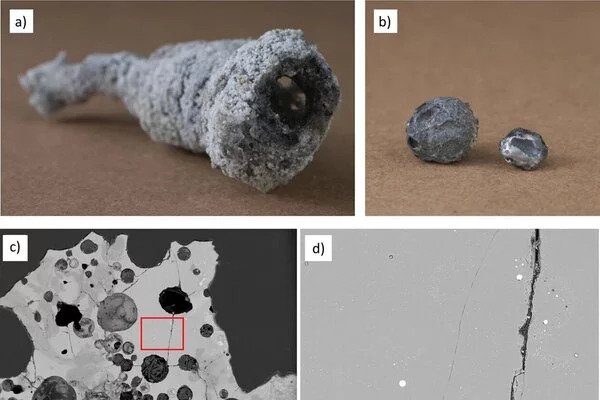

When lightning strikes a tree, the ground typically explodes and the surrounding grass dies, leaving a scar and sending electric discharge through nearby rock, soil, and sand, forming fulgurites, also known as ‘fossilized lightning.

Matthew Pasek

Pasek investigates how high-energy events, such as lightning, can cause unique chemical reactions, resulting in a new material that is transitional between space minerals and minerals found on Earth in a recent study published in Communications Earth & Environment.

“When lightning strikes a tree, the ground typically explodes and the surrounding grass dies, leaving a scar and sending electric discharge through nearby rock, soil, and sand, forming fulgurites, also known as ‘fossilized lightning,’ Pasek explained.

When the homeowners in New Port Richey discovered the ‘lightning scar,’ they discovered a fulgurite and decided to sell it, assuming it was valuable. Pasek bought it and later began working with Luca Bindi, a mineralogist, and crystallographer at the University of Florence in Italy.

Together, the team set out to investigate unusual minerals that bear the element phosphorus, especially those formed by lightning, to better understand high-energy phenomena.

“It’s critical to understand how much energy lightning has because it tells us how much damage a lightning strike can cause on average and how dangerous it is,” Pasek explained. “Florida is the world’s lightning capital, and lightning safety is critical; if lightning can melt rock, it can certainly melt people.”

According to Pasek, iron will often accumulate and encrust tree roots in wet environments such as Florida. In this case, the lightning strike not only combusted the iron on the tree roots, but it also combusted the naturally occurring carbon in the tree. The chemical reaction between the two elements produced fulgurite, which resembled a metal ‘glob.’

A colorful, crystal-like matter revealed a previously unknown material inside the fulgurite. Tian Feng, a graduate of USF’s geology program, attempted to recreate the material in the lab. The experiment was a failure, indicating that the material forms quickly under precise conditions and, if heated for too long, transforms into the mineral found in meteorites.

“Previous research indicates that lightning reduction of phosphate was a common phenomenon on the early Earth,” Feng explained. “However, Earth has an environmental phosphite reservoir issue, and these solid phosphite materials are difficult to restore.”

According to Feng, this research may reveal that other forms of reduced minerals are plausible, and many of them may have played a role in the evolution of life on Earth. Given the rarity of this material occurring naturally, Pasek believes it is unlikely that it could be mined for uses similar to other phosphates, such as fertilizer. However, Pasek and Bindi intend to conduct additional research on the material to determine whether it can be officially classified as a mineral and to raise awareness among scientists.