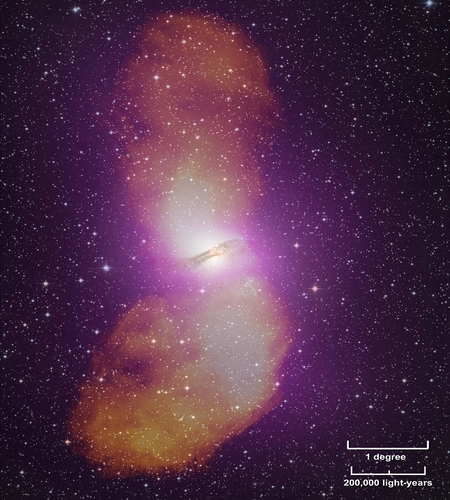

Since its discovery in 2012, astronomers have been perplexed by a glowing blob known as “the cocoon,” which appears to be inside one of the enormous gamma-ray emanations from the center of our galaxy known as the “Fermi bubbles.”

The cocoon is caused by gamma rays emitted by fast-spinning extreme stars known as “millisecond pulsars” in the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy, which orbits the Milky Way, according to new research published in Nature Astronomy. While our findings shed light on the cocoon’s mystery, they also cast doubt on efforts to find dark matter in any gamma-ray glow it may emit.

Fortunately for Earth’s life, our atmosphere blocks gamma rays. These are light particles with energies a million times greater than the photons we see with our eyes. Because our view from the ground is obscured, scientists had no idea how rich the gamma-ray sky was until instruments were launched into space. But, beginning with the chance discoveries made by the Vela satellites (which were launched into orbit in the 1960s to monitor the Nuclear Test Ban), more and more of this richness has been revealed.

Most galaxies host such giant black holes in their centers. In some, these black holes are actively gulping down matter. Thus fed, they simultaneously spew out giant, outflowing “jets” visible across the electromagnetic spectrum.

The state-of-the-art gamma-ray instrument operating today is the Fermi Gamma Ray Space Telescope, a large NASA mission in orbit for more than a decade. Fermi’s ability to resolve fine detail and detect faint sources has uncovered a number of surprises about our Milky Way and the wider cosmos.

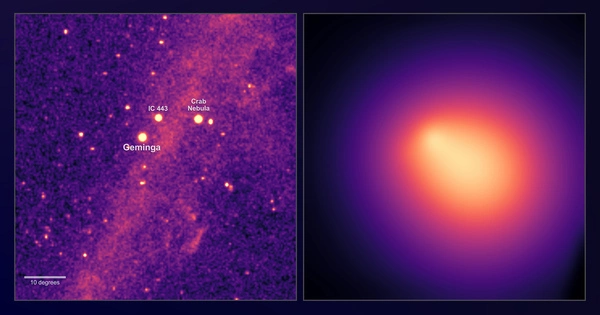

One of these surprises emerged in 2010, soon after Fermi’s launch: something in the Milky Way’s center is blowing what look like a pair of giant, gamma-ray-emitting bubbles. These completely unanticipated “Fermi bubbles” cover fully 10% of the sky.

A prime suspect for the source of the bubbles is the galaxy’s resident supermassive black hole. This behemoth, 4 million times more massive than the sun, lurks in the galactic nucleus, the region from which the bubbles emanate.

Most galaxies host such giant black holes in their centers. In some, these black holes are actively gulping down matter. Thus fed, they simultaneously spew out giant, outflowing “jets” visible across the electromagnetic spectrum.

Thus a question researchers asked after the discovery of the bubbles: can we find a smoking gun tying them to our Galaxy’s supermassive black hole? Soon, tentative evidence did emerge: there was a hint(opens in new tab), inside each bubble, of a thin gamma-ray jet pointing back towards the galactic center.

With time and further data, this picture became muddied, however. While the jet-like feature in one of the bubbles was confirmed, the apparent jet in the other seemed to evaporate under scrutiny(opens in new tab). The bubbles looked strangely lopsided: one contained an elongated bright spot the “cocoon” with no counterpart in the other bubble.