The earliest known record of human ear surgery appears to be in an ancient skull with burr holes in the temporal bones. The remains, which are considered to be female, are thought to exhibit “the first known radical mastoidectomy in human history,” according to the researchers who discovered them. An ear infection can cause inflammation and infection of the mastoid bone, which, before the introduction of medicine, often resulted in death. An ancient skull containing signs of surgical intervention to treat such an ailment, as well as indications of bone regeneration, suggests the archaic woman survived the surgery, according to the authors of new research published in the journal Scientific Reports.

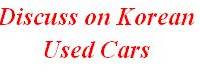

The unusual skeleton remains were discovered in a funeral chamber in Burgos, Spain, built in the 4th millennium BC and housing roughly 100 bodies. According to The History Blog, this places the skull at roughly 5,300 years old. The neurocranium was found intact, but the skull was fractured. It also revealed enough missing teeth and ossification of thyroid cartilage to indicate that the female owner died at an advanced age. Both ear canals had been surgically changed, according to computed tomography scans, most likely by a trepanation, an old-school surgical method in which a hole is bored or scraped into the human skull.

“Despite the [evidence] of cut marks, it is difficult to conclude the type of tool used to remove the bone tissue, most likely a sharp instrument with a circular movement,” the researchers explained, adding that “several studies demonstrate the use of stone instruments heated with fire as tools to cauterize wounds and perform trepanations.” While palaeopathological examinations of ancient skulls have revealed indications of mastoiditis, this is the first – to the authors’ knowledge – with signs of trepanation.

“The idea offered in this study is that the individual whose skull was found had both ears surgically intervened,” the investigators write. “Based on the discrepancies in bone remodeling between the two temporals, it indicates that the treatment was originally performed on the right ear, due to an ear pathology severe enough to necessitate intervention, which this prehistoric woman survived.” The left ear was punctured to the mastoid bone later, but the evidence does not indicate whether this was done soon after the right ear or several months or possibly years later.

Without a doubt, a painful process for a desperate prehistoric person, but an important find for human history because it marks the earliest evidence of this type of surgery and likely the first in human history. Let us all take a moment to appreciate the fact that antibiotics have surpassed stone-carved burr holes in recent years.