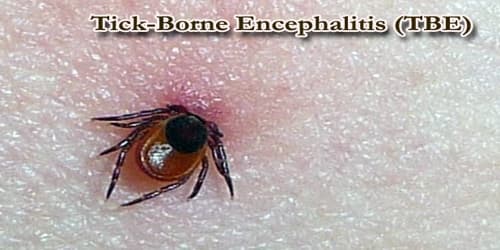

Tick-Borne Encephalitis (TBE)

Definition: Tick-borne encephalitis (TBE) is a human viral infectious disease involving the central nervous system. The disease most often manifests as meningitis, encephalitis, or meningoencephalitis. It is caused by the tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV), a member of the family Flaviviridae, and was initially isolated in 1937. The virus is transmitted by the bite of infected ticks, found in woodland habitats.

Although TBE is most commonly recognized as a neurological disorder, mild fever can also occur. Long-lasting or permanent neuropsychiatric consequences are observed in 10 to 20% of infected patients.

Infection may induce an influenza-like illness followed, in about 30% of cases, by high fever and signs of central nervous involvement. Encephalitis developing during this second phase may result in paralysis, permanent sequelae or death. The severity of illness increases with age of the patient.

The tick-borne encephalitis virus is known to infect a range of hosts including ruminants, birds, rodents, carnivores, horses, and humans. The disease can also be spread from animals to humans, with ruminants and dogs providing the principal source of infection for humans.

TBE is an important infectious disease in many parts of Europe, the Former Soviet Union, and Asia, corresponding to the distribution of the ixodid tick reservoir. The annual number of cases (incidence) varies from year to year, but several thousand cases are reported annually, despite historical under-reporting of this disease.

Causes, Sign, and Symptom: Tick-borne encephalitis virus (TBEV) of the family Flaviviridae. It was first isolated in 1937. Three virus sub-types are described: European or Western tick-borne encephalitis virus, Siberian tick-borne encephalitis virus, and Far-Eastern tick-borne encephalitis virus (formerly known as Russian spring-summer encephalitis virus).

TBEV is transmitted by the bite of infected ticks (which often remain firmly attached to the skin for days) or occasionally by ingestion of unpasteurized milk. There is no direct person-to-person transmission.

TBE cases occur in humans most frequently in rural areas and during the highest period of tick activity (between April and November). Infection also may follow the consumption of raw milk from infected goats, sheep, or cows. Laboratory infections were common before the use of vaccines and the availability of biosafety precautions to prevent exposure to infectious aerosols.

The virus can infect the brain (encephalitis), the meninges (meningitis) or both (meningoencephalitis). In general, mortality is 1% to 2%, with deaths occurring 5 to 7 days after the onset of neurologic signs.

In dogs, the disease also manifests as a neurological disorder with signs varying from tremors to seizures and death.

In ruminants, neurological disease is also present, and animals may refuse to eat, appear lethargic, and also develop respiratory signs.

In disease-endemic areas, people with recreational or occupational exposure to rural or outdoor settings (e.g., hunters, campers, forest workers, farmers) are potentially at risk for infection by contact with the infected ticks. Furthermore, as tourism expands, travel to areas of endemicity broadens the definition of who is at risk for TBE infection.

Diagnosis and Treatment: The diagnosis of TBE is based on the detection of specific IgM antibodies in cerebrospinal fluid (intrathecal production) and/or serum, mainly by ELISA. Specific IgM antibodies can persist for up to 10 months in vaccinees or individuals who acquired the infection naturally; IgG antibody cross-reaction is possibly observed with other flaviviruses.

PCR (Polymerase Chain Reaction) method is rarely used since TBE virus RNA is most often not present in patient sera or cerebrospinal fluid at the time of clinical symptoms.

There is no specific drug therapy for TBE. Meningitis, encephalitis, or meningoencephalitis requires hospitalization and supportive care based on syndrome severity. Anti-inflammatory drugs, such as corticosteroids, may be considered under specific circumstances for symptomatic relief. Intubation and ventilator support may be necessary.

Prevention: Prevention includes non-specific (tick-bite prevention, tick checks) and specific prophylaxis in the form of a vaccination. Tick-borne encephalitis vaccines are very effective and available in many disease-endemic areas and in travel clinics. Trade names are Encepur N and FSME-Immun CC.

Tickborne encephalitis virus infection can be prevented by avoiding tick bites through the following methods:

- vaccination against TBE (inactivated vaccine) is considered to be the most effective means of preventing TBE in endemic countries;

- application of tick repellents;

- wearing protective clothing, with long sleeves and long trousers tucked into socks treated with an appropriate insecticide

- inspecting the body for ticks after outdoor activities and removing ticks with tweezers or forceps; and

- avoiding the consumption of unpasteurized dairy products in risk areas.

The disease is most common in Central and Eastern Europe, and Northern Asia. About ten to twelve thousand cases are documented a year but the rates vary widely from one region to another. Most of the variation is the result of variation in the host population, particularly that of deer.

Information Source: