According to a new study published today by the Oxford Sustainable Law Programme and the Environmental Change Institute, newly available scientific evidence, which could be critical to the success of climate-related lawsuits, is frequently not produced in court.

The study reveals that evidence submitted by litigants in 73 lawsuits across 14 jurisdictions lags significantly behind state-of-the-art climate science, impeding claims that greenhouse-gas emissions caused the plaintiffs’ damages.

There was no attempt in most cases to quantify the extent to which climate change was responsible for the climate-related events causing the impacts affecting plaintiffs—an important line of evidence because not all events occur as a result of climate change.

Even fewer cases provided quantitative evidence connecting defendants’ emissions to plaintiffs’ injuries. Seventy-three percent did not cite peer-reviewed research. In addition, 48 percent of the cases involving extreme weather events claimed that the weather was caused by climate change without providing evidence.

Filling the evidentiary gap in climate litigation in Nature Climate Change, a leading interdisciplinary science journal, is the first global study on the use and interpretation of climate-science evidence in lawsuits.

From 1986 to May 2020, plaintiffs worldwide filed over 1,500 climate-related lawsuits, with the number of claims increasing. High-profile cases, such as Native Village of Kivalina v. ExxonMobil Corp, which was dismissed by the United States Court of Appeals, have demonstrated the importance of strong evidence of causation in successful litigation.

According to the study, cutting-edge, peer-reviewed attribution would allow lawyers to determine the likelihood of successful litigation before cases go to court.

‘In recent weeks, successful lawsuits in the Netherlands, Germany, and elsewhere have seen courts demand countries and companies dramatically strengthen their climate targets,’ says lead author Rupert Stuart-Smith. The power of climate litigation is becoming more apparent.

‘However, many climate-related lawsuits that have relied on evidence linking greenhouse gas emissions to climate change impacts have been unsuccessful. To have the best chance of success in litigation seeking compensation for losses caused by climate change, lawyers must make better use of scientific evidence. Climate science can answer questions raised by courts in previous cases and help these lawsuits succeed.’

‘Effective use of climate-science evidence in the courts could overcome existing obstacles to causality, set a legal precedent for demonstrating causality with climate-science evidence, and make successful litigation on climate-change impacts feasible,’ the study authors write.

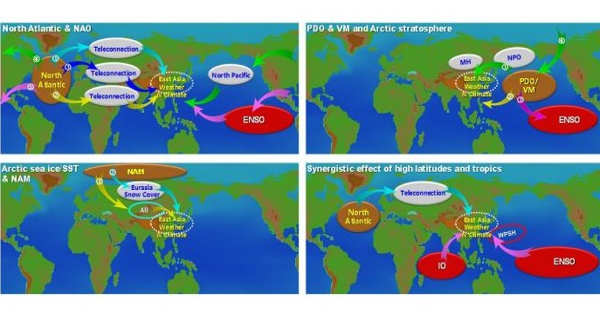

Recently, attribution science has been used to demonstrate the impact of man-made climate change on extreme weather events like Hurricane Harvey. In addition to providing better evidence, attribution science can inform the decision to pursue climate litigation cases, with uncertainties surrounding certain types of events (such as droughts) much higher than others (e.g. large-scale extreme rainfall).

‘In order to change the fate of the vast majority of climate litigation cases, courts and plaintiffs alike must recognize that science has progressed from determining that climate change is potentially dangerous to providing causal evidence linking emissions to concrete damages,’ says Dr. Friederike Otto, Associate Director of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute.

‘Holding high-emission companies accountable for their contribution to climate change is critical to driving systemic change and protecting those most vulnerable to climate change impacts,’ says Professor Thom Wetzer, Founding Director of the Oxford Sustainable Law Programme. Climate litigation aimed at achieving accountability is increasing, but the results have been mixed.

‘Our findings give us reason to be optimistic: by employing rigorous scientific evidence, litigators have the potential to be more effective than they are now.’ It is now up to litigators to translate cutting-edge science into persuasive legal arguments.’