Domino’s Pizza Inc is the largest pizza-delivery company in the world, operating more than 5,700 units throughout the United States and in 58 other countries. Domino’s was built on simple concepts, offering only delivery or carry-out and an extremely limited menu: for more than thirty years, the company offered only two sizes of pizza, eleven topping choices, and–until 1990–only one beverage, cola. In recent years the company has added salads, breadsticks, and other non-pizza items to its menu in an effort to stave off rivals Pizza Hut and Little Caesar’s, but has otherwise held fast to its focus on the basics of providing quality pizza and service.

History of Domino’s Pizza Inc

Founding in the 1960s

Tom Monaghan, founder of Domino’s Pizza, was born in 1937 near Ann Arbor, Michigan. Following his father’s death in 1941, Monaghan lived in a succession of foster homes, including a Catholic orphanage, for much of his childhood. His mother, after finishing nursing school and buying a house, made two attempts to have Tom and his brother live at home with her, but she and Tom failed to get along. During these years Monaghan worked a lot of jobs, many of them on farms. His father’s aunt took him in during his senior year of high school, but after that he was once again on his own. A quote from Monaghan in his high school yearbook read: “The harder I try to be good the worse I get; but I may do something sensational yet.”

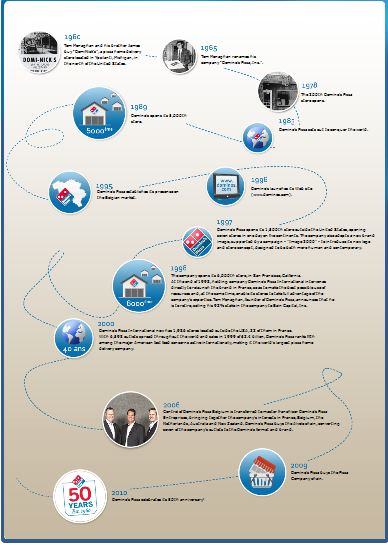

For several years Monaghan worked to try and save money for college; he joined the Marines and saved $2,000, but gave it in several installments to a fly-by-night “oil man” he met hitchhiking, who took the money and ran. Monaghan returned to Ann Arbor to live with his brother Jim, who worked for the Post Office and did occasional carpentry work at a pizza shop called DomiNick’s. When Jim Monaghan overheard the pizza shop owner discussing a possible sale, he mentioned buying it as a possibility to Tom. With the aid of a $900 loan from the Post Office credit union, in December 1960 Jim and Tom Monaghan were in business in Ypsilanti, Michigan.

Within eight months, Jim Monaghan took a beat-up Volkswagen as a trade for his half of the partnership. Tom moved in across the street from his shop. The store Monaghan bought had little room for sit-down dining; from the start, delivery was key. The first drivers, laid-off factory workers, agreed to work on commission. After only $99 in sales the first week, profits climbed steadily to $750 a week. Early on, Monaghan made decisions that streamlined work and greatly enhanced profits: on two separate occasions he dropped six-inch pizzas and submarine sandwiches from his menu when he was shorthanded at his shop, reasoning that he and his staff could handle the rush better without making special-sized pizzas or sandwiches in addition to regular pizzas. When he went over the numbers the day after, both times Monaghan found that his volume and profits had increased. Keeping the menu simple made financial sense.

Although his salary rose to $20,000 a year, Monaghan was not satisfied. On the advice of Jim Gilmore, a local chef with some restaurant experience, Monaghan opened a Pizza King store offering free delivery in Mt. Pleasant, near the Central Michigan University campus. Gilmore ran the original DomiNick’s as a full partner with Monaghan. By early 1962, although the Ypsilanti store was not doing well, Gilmore persuaded Monaghan to open a Pizza King at a new Ann Arbor location, which Gilmore would oversee while Monaghan went and whipped the original DomiNick’s back into shape. Gilmore convinced Monaghan to continue expanding in a financially dangerous way: since Gilmore had been bankrupt when the partnership began, all papers were in Monaghan’s name. By 1964, when Gilmore became ill, he made his differences clear: he liked sit-down stores while Monaghan ran delivery. He asked for $35,000 for his share in the pizzerias. Though Monaghan considered the price preposterous, he did want to separate from Gilmore. He hired lawyer Larry Sperling, who worked out a deal whereby Monaghan would pay Gilmore $20,000. Gilmore would keep two restaurants in Ann Arbor; Monaghan, two pizzerias in Ypsilanti and one in Ann Arbor. Though their partnership was dissolved, Monaghan was still dependent on Gilmore’s success in business. In February 1966 Monaghan bought one more shop from Gilmore, but later that year Gilmore filed for bankruptcy, with a total debt of $75,000, in Monaghan’s name. Monaghan managed to sell Gilmore’s restaurant, leaving him immediately responsible for only $20,000, with the new owner of Gilmore’s to pay off related debts on a month-by-month basis.

As Monaghan’s operations grew, the original owner of DomiNick’s decided to maintain rights to the name. Under deadline for a Yellow Pages ad, driver Jim Kennedy came up with the name Domino’s Pizza. The new company incorporated in 1965. Free from the Gilmore-related debts, Monaghan was ready to begin franchising. The first board of directors included Tom, his wife and bookkeeper, Margie, and Larry Sperling. Sperling drafted a franchise agreement in which Domino’s would keep 2.5 percent as royalties from sales, 2 percent to cover advertising, and 1 percent for bookkeeping. As Monaghan stated in his autobiography Pizza Tiger: “By today’s standards, the royalties were far too favorable to the franchisee. But it served our purpose then, and I was not concerned about covering all future contingencies.”

The first franchisee, Chuck Gray, was a man visible in local and state politics; he took over an original store on the east side of Ypsilanti. While Sperling and Monaghan hammered out financial matters–the former wanted to control costs, the latter to build sales–Domino’s Pizza slowly gathered a base of corporate staff. The second franchisee, Dean Jenkins, was handpicked by Monaghan to take over the first store to be built from the ground up. By July 1967, when Jenkins’s store was up and running, Domino’s Pizza moved to East Lansing, home of Michigan State University. Its dormitory population, at approximately 20,000, was the largest in the nation. Dave Kilby, originally hired to do some radio copywriting for Domino’s, later bought into a franchise, then began working at company headquarters, located above the Cross Street shop in Ypsilanti. Kilby then worked on franchisee expansion with Monaghan.

In February 1968 a fire swept through Monaghan’s original pizza store. Advertising manager Bob Cotman escaped the building just in time, climbing down a fireman’s ladder. While the pizza shop reopened within two days, headquarters was wiped out and Domino’s first commissary, with $40,000 of stored goods, was destroyed. The staff pulled together, with each existing store location responsible for producing one pizza item–cheese, dough, chopped toppings–which drivers then ferried from one store to the next to keep operations running.

The biggest challenge for Monaghan was not simply covering the total fire losses of $150,000 (only $13,000 paid for by insurance), but also paying the leases on five new franchises and finding store operators as soon as possible. While Tom worked on his task, Margie Monaghan brought in Mike Paul, her contact at the Ypsilanti bank, who soon joined Domino’s to run the commissary. Paul fired half of the staff and cleaned up operations; he introduced caps, aprons, and periodic spot checks for employee neatness.

Monaghan learned a lot in the early years of Domino’s, due in part to road trips he took to research business and learn from competitors. When observing the competition didn’t result in better methods, Monaghan innovated. Looking for equipment ideas at a Chicago convention, he found a meat-grinder which he used to chop cheese as well as mix consistent pizza dough in less than a minute, in contrast to standard mixers, which took eight to ten minutes to mix dough. Dough, once mixed, was stored on oiled pans; although covered by towels, the outside edges of the dough hardened. Monaghan discovered an air-tight fiberglass container that stored dough very well, and his practice later became a standard in the industry. Monaghan was also dissatisfied with standard pizza boxes: they were too flimsy to stack, and heat and steam from the pizza weakened them. Monaghan prodded his salesman to work with the supplier and devise a corrugated box with airholes, which also became an industry standard.

Franchising in the 1970s

Plans began in earnest for Midwest expansion as Domino’s jumped on the 1960s franchise bandwagon. While Monaghan had worked on his plan to expand on college campuses, opening a new store a week in late 1968 proved to be the beginning of a nightmare. Monaghan opened 32 stores in 1969 and was hailed as Ypsilanti’s boy wonder. Spurred by McDonald’s great success going public in 1965, Monaghan planned to do the same. With the aid of loans, he bought a fleet of 85 new delivery cars, and spruced up his personal image; he also hired an accounting firm to computerize the company’s bookkeeping. When moving information from paper to computer, Domino’s lost all its records. Perhaps as a result, the company underpaid the Internal Revenue Service by $36,000. Monaghan was forced to sell his stock for the first time to raise the money to pay the IRS.

Monaghan tried to do too much, too fast. Ohio stores opened before Domino’s reputation had spread that far and sales were poor. This was only the beginning of the downturn: on May 1, 1970, Monaghan lost control of Domino’s. Dan Quirk, who had bought Monaghan’s stock, recommended that he contact Ken Heavlin, a local man known for turning businesses around. Heavlin, in exchange for Monaghan’s remaining stock, would run the company, get loans to cover IRS debts, and after two years keep a controlling 51 percent interest in the company, with Monaghan getting 49 percent. In the meantime, Domino’s became the target of lawsuits from various franchisees, creditors, and the law firm Cross, Wrock.

In March 1971 Heavlin ended his agreement with Monaghan, who shortly went to speak with each franchisee, persuading them that Domino’s would survive the crisis and they would all fare better working with him rather than against him. Their lawsuit was dropped. Monaghan pushed on, and Domino’s was back in business, however tight its financial strings. One man instrumental in the growth of the early 1970s was Richard Mueller. Originally from Ohio, Mueller bought a franchise in Ann Arbor in 1970, during Domino’s lowest period. After Mueller ran this store for a year, Monaghan sent him to Columbus to revive an ailing store; within three months, sales shot up from $600 to $7,000 a week. Mueller soon operated ten Domino’s franchises and incorporated as Ohio Pizza Enterprises, Inc. Within six-and-a-half years Mueller opened fifty stores. As Domino’s grew, Mueller went on to become vice-president of operations in 1978.

Quick to rebuild Domino’s, Monaghan encouraged trusted employees and friends to expand. Steve Litwhiler opened five stores in Vermont, while Dave Kilby, who had relocated during the Domino’s slump, managed to build a strong base in Florida. A significant hire by Kilby was Dave Black, a top-selling manager who later rose to become president and COO of Domino’s Pizza.

The year 1973 was a turning point for Domino’s. The company introduced its first delivery guarantee, “a half hour or a half dollar off,” as stated in the company newsletter the Pepperoni Press. The College of Pizzarology was founded to train potential franchisees. The company decentralized as well: accounting was moved from Ypsilanti headquarters to local accountants, while the commissary was reorganized as a separate company.

Domino’s introduced its corporate logo, a red domino flush against two blue rectangles, in 1975. The company was sued the same year by Amstar Corporation, parent company of Domino Sugar, for the right to use the name. After a five-year battle, Domino’s won, but not until after having opened more than thirty new stores under the interim name Pizza Dispatch.

Free to expand, Domino’s planned to grow by 50 percent each year. By the late 1970s, several acquisitions contributed significantly to company growth. Domino’s merged with PizzaCo Inc., in 1978, gaining 23 open stores plus a handful more under lease. The merger with this Boulder-based company allowed Domino’s to move into Kansas, Arizona, and Nebraska. The following year, joining with Dick Mueller’s Ohio Pizza Enterprises, Inc., Domino’s added 50 stores in Ohio and Texas, for a total of 287 stores. The company ended 1979 by announcing plans to expand internationally.

Rapid Growth in the 1980s

The 1980s were a decade of phenomenal growth for Domino’s Pizza, but this time the company was prepared. While Monaghan had always feared that formal budgeting systems promoted bureaucracy, with the advice of Doug Dawson, Monaghan decided to design company-wide budgeting procedures, which Domino’s continued to use as training tools for potential franchisees. Dawson implemented the new accounting methods and moved on to become vice-president of marketing and corporate treasurer. Instrumental in Domino’s surge was John McDevitt, a financial consultant Monaghan met in 1977. Among other accomplishments, he created and became president of TSM Leasing, Inc., a financial services company which loaned money to franchisees who could not find other start-up financing.

To Monaghan, operations was the backbone of the business. When Dick Mueller left the post of vice-president of operations in 1981 to work as a franchiser once again, Monaghan decided to regionalize Domino’s operations. Mueller’s previous job entailed far too much travel, and changes were necessary. Monaghan set up six geographic regions, with a director fully responsible for each territory. The regional system, as Monaghan stated in Pizza Tiger, “gave us the long communication lines with tight controls at the working ends that we needed for rapid but well-orchestrated growth.”

At the executive level, Bob Cotman took over as senior vice-president of operations, including marketing. Dave Black advanced from field consultant and regional director to vice-president of operations. Both men (like Dick Mueller and Monaghan himself) had climbed every step of the Domino’s ladder, after beginning as delivery driver and pizza maker. In 1981 Black carried Monaghan’s favored “defensive management” strategy–whereby each store concentrated on keeping the customers it had&mdashø a new level, by moving the company’s focus away from its top-performing stores to its weakest ones. Bringing the lower performers up worked extremely well. As the company added an average of nearly 500 stores each year through the decade, newer, weaker stores were constantly given attention to improve sales.

One other element vital to Domino’s 1980s growth spurt was choosing Don Vlcek, formerly in the meat business, to head the eight commissary operations. Vlcek focused on focused on uncovering best practices and disseminating them throughout the organization. When he discovered that one commissary saved on laundry bills by rinsing out the towels used to dry trays, making them last a week before cleaning was necessary, Vlcek made all other commissaries do the same. When he found that another commissary’s manager was buying from a local cheese distributor instead of a less-expensive national one, the manager reworked his purchasing policies. Vlcek moved sauce-mixing from the commissaries to the company’s tomato-packing plant, which resulted in highly consistent, quality pizza sauce. Once Vlcek had taken care of the basics, in one eight-month period he opened a new commissary a month, all with state-of-the-art equipment.

All the support Monaghan received gave him time to fulfill boyhood dreams on a dramatic scale. In 1983 he bought the Detroit Tigers baseball team, which went on to win the World Series in 1984. He followed with the establishment of Domino’s Farms in Ann Arbor, a $120 million corporate headquarters modeled after architect Frank Lloyd Wright’s Golden Beacon tower. Wright advocated the integration of a high-rise building in a rural setting, rather than an urban one. Monaghan planned to set up a working farm adjacent to the tower.

In 1985, Advertising Age placed Domino’s “among the fastest-growing money makers in the restaurant industry.” The company had to keep pace with not only its own growth but with that of its competition, including the industry leader, Pizza Hut, which had more than 4,000 units to Domino’s 2,300. Domino’s stepped up advertising, increasing media spending 249 percent over the previous year. Pizza Hut entered the delivery business in 1986, posing a huge threat to Monaghan’s empire.

Domino’s sales reached $1.44 billion by 1987. The company had grown to 3,605 units, spreading to Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom, West Germany, and Japan. While 33 percent of U.S. stores were company-run, international units were franchised, usually to one operator who could opt to subfranchise. The international marketing challenge was to convince buyers of the need for delivery. Back in the United States, Domino’s imitated McDonald’s by tailoring an ad campaign to attract the Hispanic market. Competition in the late 1980s got so tough that Monaghan was quoted in Advertising Age as saying, “I want people here in the company to think of it as a war.” Unfortunately, with wars come casualties.

By 1989 more than 20 deaths had occurred involving Domino’s drivers, calling the company’s 30-minute delivery guarantee into question. A Pittsburgh-based attorney representing a couple whose car was broadsided by a driver subpoenaed Domino’s for its records. Citizen’s groups, major news networks, and the National Safe Work Place Institute joined in the heated criticism. Domino’s responded with a national ad campaign and with various tactics at the franchise level. One franchisee hired an off-duty police officer to track his drivers to ensure that they obeyed the law.

Domino’s opened its 5,000th store by January 1989, moving into Puerto Rico, Mexico, Guam, Honduras, Panama, Colombia, Costa Rica, and Spain. U.S. sales hit $2 billion. Monaghan named Dave Black as president and chief operating officer, announcing his own intentions to spend more time on community work. In May Domino’s introduced pan pizza, its first new product in 28 years. This news was hardly as big, however, as Monaghan’s October announcement of his intent to sell the company. After a buyout attempt in the form of an employee stock ownership plan failed, Monaghan went shopping for buyers. By April 1990 Domino’s cut its public relations and international marketing departments and continued cutting executive and corporate support staff as part of a company-wide effort to improve profitability. Payroll that year decreased by $24 million. Kevin Williams, who made his name as a regional director, replaced Mike Orcutt as vice-president of operations. At the store level, Domino’s opened fewer than 300 units in both 1989 and 1990.

Retrenching for the 1990s and Beyond

With Domino’s sales slipping, and rivals Pizza Hut and Little Caesar’s gaining market share, Monaghan returned to Domino’s in March 1991 to pull his company back on track. By December he had fired David Black, along with other top executives. Former franchisee Phil Bressler became vice-president of operations. Domino’s closed 155 stores, cut regional offices from 16 to 9, and unloaded extravagances such as corporate planes, a three-masted ship, a travel agency, a lavish Ann Arbor Christmas display, and various sports sponsorships. Monaghan made some personal sacrifices too, leaving his post on the boards of directors of 16 Catholic colleges and organizations. Domino’s 1991 revenues remained flat at $2.6 billion, and the company posted a loss of $67 million.

Adding three new senior executives, the company geared up to battle Pizza Hut, which had aired an ad showing unkempt Domino’s drivers buying Pizza Hut products. Domino’s moved its advertising accounts to New York’s Grey Advertising, Inc., from the local ad agency Group 243. While Monaghan was away, Pepsico’s Pizza Hut had converted half of its 7,000 units for home delivery.

Under fire, Monaghan insisted on maintaining Domino’s original concept of a simple menu that speeds order preparation, allowing the company to uphold its 30-minute guarantee. In an effort to be flexible–and to compete with Pizza Hut’s pan pizza–Domino’s offered a new pizza with more cheese and an increased number of toppings. Taking another tip from its rival, Domino’s worked on developing a single U.S. phone order number for Domino’s customers and a new computer system to track sales, costs, and trends. The company closed the Columbus and Minneapolis offices, with corporate headquarters in Ann Arbor assuming their duties. The overall goal was to decrease debt. Monaghan considered making a public stock offering again in 1992, but too few buyers were forthcoming. The company also worked to lessen the number of company-owned stores.

In November 1992 Monaghan shook up his upper ranks by replacing his longtime adviser and vice-president of finance, John McDevitt, with Tim Carr, another financial executive at Domino’s, and hiring Larry Sheehan, a former executive vice-president of Little Caesar’s, as vice-president of marketing and product development. Sheehan immediately put his stamp on the turnaround effort, convincing Monaghan to experiment with new strategies and products, including salads, thin-crust pizza, and submarine sandwiches. “Tom Monaghan is now very open about the pizza business,” he said. “He believes we need to take a different approach to this business and be willing to change.”

And the changes seemed to work. Earnings for 1993 picked up, after dropping significantly the two previous years. In yet another change, Domino’s dropped its famous 30-minutes-or-less pledge after a jury awarded a $78 million settlement to a woman who had been hit by a Domino’s delivery driver in 1989. Monaghan stated that “with our success in home delivery has come a negative public perception that we are not committed to safety.”

In January 1994 Larry Sheehan left Domino’s, after a dispute with Monaghan over the size of his year-end bonus. While his departure was widely considered a loss to the company, his changes had taken hold, and Domino’s revenues crept upward, to $2.5 billion in 1995. Shortly thereafter Domino’s celebrated the opening of its 1,000th international store, in a suburb of Perth, Australia. With a stated goal of having more international than domestic stores, Domino’s opened stores in Ecuador, Peru, and Egypt in 1995, and planned to have 3,000 international stores by the year 2,000. By 1996 foreign sales stood at $503 million, and in 1997 Domino’s entered its 50th international market.

Sheehan was succeeded as vice-president of marketing and product development by Cheryl Bachelder, a seasoned executive with experience at Planters, Gillette, and Procter & Gamble who brought focus to Domino’s efforts. “We’re not trying to be fun and wacky and do delivery and carry-out all at the same time,” she said. “We’re trying to excel single-mindedly on the basics of this business.” In March 1997 Domino’s announced its previous year results, which dispelled any doubts that the company was back on track. Earnings were a record $50.6 million on sales of $2.8 billion. “We believe the return to focusing on our core business–pizza delivery–coupled with great new products and strong international growth accounted for our tremendous results in 1996,” said CFO Harry Silverman.

For his part, Monaghan says that he’s back to stay. “I plan on being at the helm a long time–at least fifteen years,” he said. “Basically, God meant me to be a pizza man. Pizza is my life.”