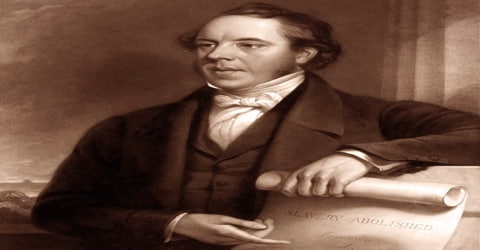

Biography of Thomas Clarkson

Thomas Clarkson – English abolitionist, and a leading campaigner.

Name: Thomas Clarkson

Date of Birth: 28 March 1760

Place of Birth: Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, England

Date of Death: 26 September 1846 (aged 86)

Place of Death: Playford, Suffolk, England

Spouse: Catherine Buck (m. 1796–1846)

Children: Thomas

Early Life

Thomas Clarkson was an English abolitionist, born on March 28, 1760, in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, to a wealthy family. He was an English abolitionist and a leading campaigner against the slave trade in the British Empire. He helped found The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (also known as the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade) and helped achieve passage of the Slave Trade Act of 1807, which ended British trade in slaves.

Born in Cambridgeshire to a financially well-off family, he wanted to become a reverend like his father, John Clarkson, who was also the headmaster of the Wisbech Grammar School where Thomas began his schooling. An outstanding student, he graduated from St. John’s College, Cambridge. Following in his father’s footsteps he planned to join the Angelical Church and was ordained as a deacon, but he never proceeded to the priest’s orders. After participating in a Latin essay-writing competition, he believed he had a spiritual experience. The topic of the essay was ‘Anne liceat invitos in servitutem dare’ (Is it lawful to enslave the unconsenting?) and he won the competition. While researching for it, he learned about the hideous profession of the slave trade and the inhumane concept of slavery.

Clarkson was ordained a deacon, but from 1785 he devoted his life to abolitionism. His An Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species (1786) brought him into association with Granville Sharp, William Wilberforce, and other foes of slavery. In 1787 he joined them in forming a society for the abolition of the slave trade. His essay also gained him the sympathy of Edmund Burke, Charles James Fox, and the younger William Pitt.

In his later years, Clarkson campaigned for the abolition of slavery worldwide; it was then concentrated in the Americas. In 1840, he was the key speaker at the Anti-Slavery Society’s (today known as Anti-Slavery International) first conference in London, which campaigned to end slavery in other countries.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Thomas Clarkson was born on March 28, 1760, in Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, England to Rev. John Clarkson and Anne. John Clarkson was an Anglican priest and the headmaster at the Wisbech Grammar School.

Thomas received his primary schooling from Wisbech Grammar School and went on to St. Paul’s School, London, in 1775. e did his undergraduate work at St John’s College, Cambridge, beginning in 1779. An excellent student, he appears to have enjoyed his time at university, although he was also a serious, devout man. He received his BA degree in 1783 and was set to continue at Cambridge to follow in his father’s footsteps and enter the Anglican Church. He was ordained a deacon but never proceeded to priest’s orders.

Thomas Clarkson was an outstanding student and wanted to become a reverend like his father. He joined the Anglican Church to follow in his father’s footsteps and was ordained as a deacon. But he never proceeded to taking his holy orders. After participating in a Latin essay-writing competition, he believed he had a spiritual experience. The topic of the essay was ‘Is it lawful to enslave the unconsenting?’ and he won the competition.

While researching the topic, he learned about the inhumane concept of slavery and the hideous practice of slave trading through Anthony Benezet’s book on the same topic.

Personal Life

In 1796 Thomas Clarkson married Catherine Buck of Bury St Edmunds, Suffolk; their only child Thomas was born in 1796. They moved back to the south of England for the sake of Catherine’s health and settled at Bury St Edmunds from 1806 to 1816. Next, they lived at Playford Hall, located halfway between Ipswich and Woodbridge, Suffolk.

Career and Works

It was at Cambridge in 1785 that Clarkson entered a Latin essay competition that was to set him on the course for most of the remainder of his life. The topic of the essay, set by university vice-chancellor Peter Peckard, was Anne liceat invitos in servitutem dare (“Is it lawful to enslave the unconsenting?”), and it led Clarkson to consider the question of the slave trade. He read everything he could on the subject, including the works of Anthony Benezet, a Quaker abolitionist, as well as firsthand accounts of the African slave trade such as Francis Moore’s Travels into the Interior Parts of Africa. Appalled and challenged by what he discovered, Clarkson changed his life. He also researched the topic by meeting and interviewing those who had personal experience of the slave trade and of slavery.

In 1786, he translated his essay into a pamphlet in English for a wider audience and named it ‘An essay on the slavery and commerce of the human species, particularly Africa, translated from a Latin Dissertation’. The essay gained claim and importance and he soon met other leading campaigners against slave trade including James Ramsay, Granville Sharp, and other Nonconformists.

From his new acquaintances, he came to know that a movement, initiated by the Quakers, against slavery had been gathering strength for years in 1783, a group of 300 Quakers had signed the first petition against the slave trade and presented it to the Parliament.

Clarkson visited British ports to collect facts for his pamphlet “A Summary View of the Slave Trade and of the Probable Consequences of Its Abolition” (1787). The evidence that he gathered was used in the antislavery campaign led by Wilberforce in Parliament. Little progress was made during the early years of warfare with France because many members of Parliament believed that the slave trade provided essential wealth for the nation and valuable training for the navy.

In 1787, 12 men, including Thomas Clarkson, founded the Committee for Abolition of the African Slave Trade. Of the 12 members, nine were Quakers and the rest were Anglicans Clarkson being one of the three. Granville Sharp was elected as the Chairman. Thomas’ main role in the committee was gathering evidence against the trade, but as it was legal and highly profitable, he faced stern opposition when he tried to educate people about the evil practice.

Liverpool was a major base of slave trading syndicates and home port for their ships. In 1787, Clarkson was attacked and nearly killed when visiting the city, as a gang of sailors was paid to assassinate him. He barely escaped with his life. Elsewhere, however, he gathered support. Clarkson’s speech at the collegiate church in Manchester (now Manchester Cathedral) on 28 October 1787 galvanized the anti-slavery campaign in the city. That same year, Clarkson published the pamphlet A Summary View of the Slave Trade and of the Probable Consequences of Its Abolition.

His mission led him to the port at Bristol where the landlord of the Seven Stars Pub provided him with all the information he might need. On traveling further, he met two surgeons who had been on many voyages aboard slave ships. They recounted their experiences and this information too was used in the campaign.

In his two years of evidence-gathering, he traveled over 35,000 miles on horseback and interviewed around 20,000 sailors. He also took numerous equipment (iron handcuffs, leg-shackles, branding irons, thumbscrews), that were used to capture and torture the slaves, as evidence.

In 1791 Wilberforce introduced the first Bill to abolish the slave trade; it was easily defeated by 163 votes to 88. As Wilberforce continued to bring the issue of the slave trade before Parliament, Clarkson traveled and wrote anti-slavery works. Based on a plan of a slave ship he acquired in Portsmouth, he had an image drawn of slaves loaded on the slave ship Brookes; he published this in London in 1791, took the image with him on lectures, and provided it to Wilberforce with other anti-slave trade materials for use in parliament.

Thomas Clarkson retired from the campaign in 1794 due to his failing health but returned with full vigor and optimism in 1804 after the war ended. However, this time his major emphasis lay in lobbying MPs to support the parliamentary campaign. His efforts finally bore fruit with the passing of the Slave Trade Act in 1807. The Act also called on the British Navy to enforce and uphold this law. With this success, he took his campaigning to the rest of Europe.

Passage of the Slave Trade Act in 1807 ended the trade and provided for British naval support to enforce the law. Clarkson directed his efforts toward enforcement and extending the campaign to the rest of Europe, as Spain and France continued to trade in their American colonies. The United States also prohibited international trade in 1807 and operated chiefly in the Caribbean to interdict illegal slave ships.

In 1808 Clarkson published a book about the progress in the abolition of the slave trade. He traveled to Paris in 1814 and Aix-la-Chapelle in 1818, trying to reach international agreement on a timetable for the abolition of the trade. He contributed the article on the “Slave Trade” for Rees’s Cyclopædia, Vol. 33, 1816.

In 1807 a bill for the abolition of the slave trade finally was passed, and the next year Clarkson’s two-volume history of the trade was published. Partly as a result of Clarkson’s continued efforts, Viscount Castlereagh in 1815 secured the condemnation of the trade by the other European powers, though at the congress of Aix-la-Chapelle (1818) measures for enforcing international abolition were discussed without effect. When the Anti-Slavery Society was founded (1823), Clarkson was chosen a vice president.

In 1823, he helped in the establishment of the Society for Mitigation and Gradual Abolishment of Slavery. He traveled for over 10,000 miles and created linkages between the countless newly formed anti-slavery societies. His efforts didn’t go in vain as the parliament received 777 petitions for the total emancipation of the slaves. Owing to the public pressure, the Slavery Abolition Act was passed in 1833; it ordered for complete emancipation in the British colonies by 1838.

(Thomas Clarkson is the central figure in this painting which is of the 1840 Anti-Slavery Convention.)

In 1846 Clarkson was host to Frederick Douglass, an American former slave who had escaped to freedom in the North and became a prominent abolitionist, on his first visit to England. Douglass spoke at numerous meetings and attracted considerable attention and support. At risk after passage in the US of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, Douglass was grateful when British friends raised the money and negotiated the purchase of his freedom from his former master.

Awards and Honor

Thomas Clarkson was awarded the title of Domestic Chaplain to the Earl of Portmore in 1785.

In 1834, after the abolition of slavery in Jamaica, Free Villages were founded for the settlement of freedmen. The town of Clarksonville, named in his honor, was established in St. Ann, Jamaica.

In July 2010, the Church of England Synod added Clarkson to the list of people to be honored in a “lesser festival” in the church calendar of saints; they are recognized on 30 July, the same day as William Wilberforce. An initial celebration was held in Playford Church on 30 July 2010.

Death and Legacy

Thomas Clarkson passed away on September 26, 1846, in Playford, Suffolk, and he was buried in St. Mary’s Church.

Thomas was not the only notable member of his family. His younger brother John Clarkson (1764-1828) at age 28 took a major part in organizing and coordinating the relocation of approximately 1200 Black Loyalists to Africa in early 1792. They were among the 3000 United States ex-slaves given their freedom by the British and granted land in Nova Scotia, Canada, after the American Revolutionary War. This group chose to go to the new colony of Sierra Leone founded by the British in West Africa, founding Freetown.

Thomas Clarkson’s biggest achievement was the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act in 1833, which was mostly possible because of his extensive campaigning. He also co-founded the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (also known as the Society for the Abolition of the Slave Trade).

Information Source: