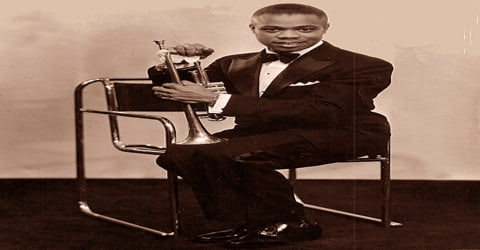

Biography of Louis Armstrong

Louis Armstrong – American trumpeter, composer, vocalist, and occasional actor.

Name: Louis Daniel Armstrong

Date of Birth: August 4, 1901

Place of Birth: New Orleans, Louisiana, United States

Date of Death: July 6, 1971 (aged 69)

Place of Death: Corona, New York City, New York, United States

Occupation: Musician, Composer, Singer

Father: William Armstrong

Mother: May-Ann

Spouse/Ex: Alpha Smith, Daisy Parker, Lil Hardin, Lucille Wilson

Early Life

Louis Armstrong, the leading trumpeter and one of the most influential artists in jazz history, was born on July 4, 1900, in New Orleans, Louisiana, United States, to Mary Albert and William Armstrong. His career spanned five decades, from the 1920s to the 1960s, and different eras in the history of jazz. In 2017, he was inducted into the Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame.

Famous for his innovative methods of playing the trumpet and cornet, Armstrong was also a highly talented singer blessed with a powerful gravelly voice. Known for his improvisation skills, Armstrong could bend and twist the lyrics and melody of a song with dramatic effects. Coming to prominence in the mid 20th century America when racism was much prevalent, he was one of the first African-American entertainers to be highly popular among both the white and the colored segments of the society. Fondly nicknamed Satchmo or Pops by his fans, he is often regarded to be the founding father of jazz as a uniquely American art form. Born into poverty in New Orleans, he had a very difficult childhood after his father abandoned the family. As a young boy, he sought solace in music and started playing musical instruments as a teenager to earn his living. He soon discovered that he was naturally gifted in music and over a period of years established himself as a much-respected player of jazz music. He entertained millions over the course of his long and illustrious career and went on to become one of the first great celebrities of the 20th century.

Armstrong’s influence extends well beyond jazz, and by the end of his career in the 1960s, he was widely regarded as a profound influence on popular music in general. Armstrong was one of the first truly popular African-American entertainers to “cross over”, that is, whose skin color became secondary to his music in an America that was extremely racially divided at the time. He rarely publicly politicized his race, often to the dismay of fellow African Americans, but took a well-publicized stand for desegregation in the Little Rock crisis. His artistry and personality allowed him access to the upper echelons of American society, then highly restricted for black men.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Louis Daniel Armstrong, byname Satchmo (truncation of “Satchel Mouth”), nicknamed Satch, and Pops, was born on August 4, 1901, in New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S., to William Armstrong, a factory worker, and Mary Albert. His family was very poor. His father abandoned the family when Louis was young, and his mother often had to resort to prostitution to provide for the family.

As a youngster, Armstrong sang on the streets with friends. His parents separated when he was five. He lived with his sister, mother, and grandmother in a rundown area of New Orleans known as “the Battlefield” because of the gambling, drunkenness, fighting, and shooting that frequently occurred there.

At six Armstrong attended the Fisk School for Boys, a school that accepted black children in the racially segregated system of New Orleans. He did odd jobs for the Karnoffskys, a family of Lithuanian Jews. While selling coal in Storyville, he heard spasm bands, groups that played music out of household objects. He heard the early sounds of jazz from bands that played in brothels and dance halls such as Pete Lala’s, where King Oliver performed.

Armstrong had to drop out of school in order to work and augment his mother’s meager income. He started singing in the streets for money and also began working for a Jewish family, the Karnofskys, who treated young Louis as a family member and encouraged his musical talents. He fired his step-father’s gun in the air during a New Year’s Eve celebration in 1912 and was arrested and sent to the Colored Waif’s Home (a reform school) for Boys. There he received musical instruction and realized that he had a natural talent for playing the cornet. By the time he was released from the home in 1914, he had realized that his life’s calling was to make music.

On June 14, 1914, Armstrong was released into the custody of his father and his new stepmother, Gertrude. He lived in this household with two stepbrothers for several months. After Gertrude gave birth to a daughter, Armstrong’s father never welcomed him, so he returned to his mother, Mary Albert. In her small home, he had to share a bed with his mother and sister. His mother still lived in The Battlefield, leaving him open to old temptations, but he sought work as a musician. He found a job at a dance hall owned by Henry Ponce, who had connections to organized crime. He met the six-foot tall drummer Black Benny, who became his guide and bodyguard. Armstrong played in brass band parades in New Orleans. He listened to the music of local musicians such as Kid Ory and his idol, King Oliver.

Personal Life

Louis Armstrong was married four times. His first marriage was to a former prostitute named Daisy Parker on March 19, 1919, at City Hall. They adopted a three-year-old boy, Clarence, whose mother, Armstrong’s cousin Flora, had died soon after giving birth. Clarence Armstrong was mentally disabled as the result of a head injury at an early age, and Armstrong spent the rest of his life taking care of him. The marriage was tumultuous from the very beginning and soon ended in divorce. He had adopted a young boy called Clarence over the course of this marriage.

On February 4, 1924, Armstrong married Lil Hardin Armstrong, King Oliver’s pianist. She had divorced her first husband a few years earlier. His second wife helped him develop his career, but they separated in 1931 and divorced in 1938. Armstrong then married Alpha Smith. His marriage to his third wife lasted four years, and they divorced in 1942.

His fourth and final marriage was to a singer at the Cotton Club, Lucille Wilson in October 1942, to whom he was married until his death in 1971.

Even though Armstrong never had children from any of his marriages, a new controversy emerged in 2012 when a woman named Sharon Preston claimed that she was his biological daughter from a 1950s affair he had with a dancer named Lucille Preston. Personal letters Armstrong had written in the 1950s confirm the fact that he believed Sharon to be his daughter and paid for her upbringing. A prolific musician, Armstrong led a very hectic life often performing up to 300 concerts a year. His lifestyle began taking its toll on his health during the late 1960s and he began suffering from kidney and heart problems.

Career and Works

Louis Armstrong played in brass bands and riverboats in New Orleans, first on an excursion boat in September 1918. He traveled with the band of Fate Marable, which toured on the steamboat Sidney with the Streckfus Steamers line up and down the Mississippi River. Marable was proud of his musical knowledge, and he insisted that Armstrong and other musicians in his band learn sight reading. Armstrong described his time with Marable as “going to the University”, since it gave him a wider experience working with written arrangements. He did return to New Orleans periodically. In 1919, Oliver decided to go north and resigned his position in Kid Ory’s band; Armstrong replaced him. Armstrong also became the second trumpet for the Tuxedo Brass Band.

In the early 1920s, Armstrong played in Mississippi riverboat dance bands. Fame beckoned in 1922 when Oliver, then leading a band in Chicago, sent for Armstrong to play the second cornet. Oliver’s Creole Jazz Band was the apex of the early, contrapuntal New Orleans ensemble style, and it included outstanding musicians such as the brothers Johnny and Baby Dodds and pianist Lil Hardin, who married Armstrong in 1924. The young Armstrong became popular through his ingenious ensemble lead and second cornet lines, his cornet duet passages (called “breaks”) with Oliver, and his solos. He recorded his first solos as a member of the Oliver band in such pieces as “Chimes Blues” and “Tears,” which Lil and Louis Armstrong composed.

Looking for better career prospects, Armstrong left Oliver in 1924 and joined Fletcher Henderson’s Orchestra, the top African-American dance band in New York City at the time. Again he proved to be much successful and soon transformed Henderson’s band into what is today regarded as the first jazz big band. The Great Depression set in during the late 1920s, and Armstrong’s hitherto thriving career suffered a setback. The depression caused several of the prominent clubs where he played to shut down. Many of his fellow musicians shifted to other professions to make a living.

Armstrong’s first studio recordings were with Oliver for Gennett Records on April 5–6, 1923. They endured several hours on the train to remote Richmond, Indiana, and the band was paid little. The quality of the performances was affected by a lack of rehearsal, crude recording equipment, bad acoustics, and a cramped studio. In addition, Richmond was associated with the Ku Klux Klan. Armstrong and Oliver parted amicably in 1924. Shortly afterward, Armstrong received an invitation to go to New York City to play with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra, the top African-American band of the time. Armstrong switched to the trumpet to blend in better with the other musicians in his section. His influence on Henderson’s tenor sax soloist, Coleman Hawkins, can be judged by listening to the records made by the band during this period. During this time, Armstrong recorded with Clarence Williams (a friend from New Orleans), the Williams Blue Five, Sidney Bechet, and blues singers Alberta Hunter, Ma Rainey, and Bessie Smith.

When Armstrong returned to Chicago in the fall of 1925, he organized a band and began to record one of the greatest series in the history of jazz. These Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings show his skill and experimentation with the trumpet. In 1928 he started recording with drummer Zutty Singleton and pianist Earl Hines, the latter a musician whose skill matched Armstrong’s. Many of the resulting records are masterpieces of detailed construction and adventurous rhythms. During these years Armstrong was working with big bands in Chicago clubs and theaters. His vocals featured on most records after 1925, are an extension of his trumpet playing in their rhythmic liveliness and are delivered in a unique throaty style. He was also the inventor of scat singing (the random use of nonsense syllables), which originated after he dropped his sheet music while recording a song and could not remember the lyrics.

In the first half of 1927, Armstrong assembled his Hot Seven group, which added drummer Al “Baby” Dodds and tuba player, Pete Briggs, while preserving most of his original Hot Five lineup. John Thomas replaced Kid Ory on trombone. Later that year he organized a series of new Hot Five sessions which resulted in nine more records. In the last half of 1928, he started recording with a new group: Zutty Singleton (drums), Earl Hines (piano), Jimmy Strong (clarinet), Fred Robinson (trombone), and Mancy Carr (banjo).

Armstrong retained vestiges of the style in such masterpieces as “Hotter than That,” “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue,” “Wild Man Blues,” and “Potato Head Blues” but largely abandoned it while accompanied by pianist Earl Hines (“West End Blues” and “Weather Bird”). By that time Armstrong was playing trumpet, and his technique was superior to that of all competitors. Altogether, his immensely compelling swing; his brilliant technique; his sophisticated, daring sense of harmony; his ever-mobile, expressive attack, timbre, and inflections; his gift for creating vital melodies; his dramatic, often complex sense of solo design; and his outsized musical energy and genius made these recordings major innovations in jazz.

Armstrong was a famous musician by 1929 when he moved from Chicago to New York City and performed in the theatre review ‘Hot Chocolates’, he sang “Fats” Waller’s (1904–1943) “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” Armstrong’s first popular song hit. He moved to Los Angeles in 1930 and played at the New Cotton Club. The club was often visited by the Hollywood crowd, and celebrities like Bing Crosby were regulars there. However, Armstrong did not stay there for long and returned to Chicago in late 1931. He traveled a lot during the 1930s and visited countries like Britain, Denmark, France, Scandinavia, and Holland where he gave concerts. His popularity as a performer reached new heights during the late 1930s.

From this period Armstrong performed mainly popular song material, which presented a new challenge. Some notable performances resulted. His trumpet playing reached a peak around 1933. His style then became simpler, replacing the experimentation of his earlier years with a more mature approach that used every note to its greatest advantage. He re-recorded some of his earlier songs with great results.

Armstrong also ventured into films and played a bandleader in the motion picture ‘Pennies from Heaven’ with Bing Crosby in 1936, becoming the first African-American to get featured billing in a major Hollywood movie. He also appeared in several other movies with big Hollywood stars in the ensuing years.

During this time Armstrong abandoned the often blues-based original material of his earlier years for a remarkably fine choice of popular songs by such noted composers as Hoagy Carmichael, Irving Berlin, and Duke Ellington. With his new repertoire came a new, simplified style: he created melodic paraphrases and variations as well as chord-change-based improvisations on these songs. His trumpet range continued to expand, as demonstrated in the high-note showpieces in his repertoire. His beautiful tone and gift for structuring bravura solos with brilliant high-note climaxes led to such masterworks as “That’s My Home,” “Body and Soul,” and “Star Dust.” One of the inventors of scat singing, he began to sing lyrics on most of his recordings, varying melodies or decorating with scat phrases in a gravel voice that was immediately identifiable. Although he sang such humorous songs as “Hobo, You Can’t Ride This Train,” he also sang many standard songs, often with an intensity and creativity that equaled those of his trumpet playing.

Armstrong continued performing and recording throughout the 1940s and 1950s, releasing a string of super hits like ‘Blueberry Hill’, ‘That Lucky Old Sun’, ‘La Vie En Rose’, and ‘I Get Ideas’. During the mid-1950s his international popularity skyrocketed and he embarked on world tours to several countries, performing in front of sold-out crowds in Europe, Africa, and Asia.

Armstrong continued to front big bands, often of lesser quality, until 1947, when the big-band era ended. He returned to leading a small group that, though it included first-class musicians at first, became a mere background for his talents over the years. During the 1930s Armstrong had achieved international fame, first touring Europe as a soloist and singer in 1932. After World War II (1939–45) and his 1948 trip to France, he became a constant world traveler. He journeyed through Europe, Africa, Japan, Australia, and South America. He also appeared in numerous films, the best of which was a documentary titled Satchmo the Great (1957).

Armstrong performed in Italy at the 1968 Sanremo Music Festival where he sang “Mi Va di Cantare” alongside his friend, the Eritrean-born Italian singer Lara Saint Paul. In February 1968, he also appeared with Lara Saint Paul on the Italian RAI television channel where he performed “Grassa e Bella”, a track he sang in Italian for the Italian market and C.D.I. label.

In most of Armstrong’s movie, radio, and television appearances, he was featured as a good-humored entertainer. He played a rare dramatic role in the film New Orleans (1947), in which he also performed in a Dixieland band. This prompted the formation of Louis Armstrong’s All-Stars, a Dixieland band that at first included such other jazz greats as Hines and trombonist Jack Teagarden. For most of the rest of Armstrong’s life, he toured the world with changing All-Stars sextets; indeed, “Ambassador Satch” in his later years was noted for his almost nonstop touring schedule. It was the period of his greatest popularity; he produced hit recordings such as “Mack the Knife” and “Hello, Dolly!” and outstanding albums such as his tributes to W.C. Handy and Fats Waller. In his last years, ill health curtailed his trumpet playing, but he continued as a singer. His last film appearance was in Hello, Dolly! (1969).

The public had come to think of Louis Armstrong as a vaudeville entertainer (a light, often comic performer) in his later years a fact reflected in much of his recorded output. But there were still occasions when he produced well-crafted, brilliant music.

Awards and Honor

Louis Armstrong was posthumously awarded the Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1972 by the Academy of Recording Arts and Sciences.

The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame listed Armstrong’s West End Blues on the list of 500 songs that shaped Rock and Roll.

In 1999 Armstrong was nominated for inclusion in the American Film Institute’s 100 Years … 100 Stars.

Death and Legacy

Louis Armstrong died of a heart attack in his sleep on July 6, 1971, a month before his 70th birthday, at his home in Queens, New York. He was interred in Flushing Cemetery, Flushing, in Queens, New York City. His honorary pallbearers included Bing Crosby, Ella Fitzgerald, Dizzy Gillespie, Pearl Bailey, Count Basie, Harry James, Frank Sinatra, Ed Sullivan, Earl Wilson, Alan King, Johnny Carson, and David Frost. Peggy Lee sang The Lord’s Prayer at the services while Al Hibbler sang “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” and Fred Robbins, a long-time friend, gave the eulogy.

More than a great trumpeter, Louis Armstrong was a bandleader, singer, soloist, film star, and comedian. One of his most remarkable feats was his frequent conquest of the popular market with recordings that thinly disguised authentic jazz with Armstrong’s contagious humor. He nonetheless made his greatest impact on the evolution of jazz itself, which at the start of his career was popularly considered to be little more than a novelty. With his great sensitivity, technique, and capacity to express emotion, Armstrong not only ensured the survival of jazz but led in its development into a fine art.

Armstrong’s 1954 studio release ‘Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy’ is considered to be one of his masterpieces. Featuring timeless hits like ‘St. Louis Blues’, ‘Yellow Dog Blues’, ‘Loveless Love’, and ‘Aunt Hagar’s Blues’, the album is described by Allmusic as “essential music for all serious jazz collections”. His 1967 single ‘What a Wonderful World’ was an iconic song that peaked at No.1 in Austria and U.K. and reached the top ten in several other countries like Denmark, Belgium, Ireland, and Norway.

In the summer of 2001, in commemoration of the centennial of Armstrong’s birth, New Orleans’s main airport was renamed Louis Armstrong New Orleans International Airport. In 2002, the Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings (1925–1928) were preserved in the United States National Recording Registry, a registry of recordings selected yearly by the National Recording Preservation Board for preservation in the National Recording Registry of the Library of Congress. The US Open tennis tournament’s former main stadium was named Louis Armstrong Stadium in honor of Armstrong who had lived a few blocks from the site.

Information Source: