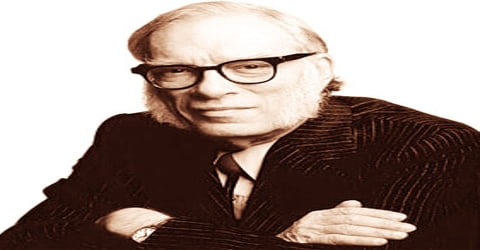

Biography of Isaac Asimov

Isaac Asimov – American writer and professor of biochemistry.

Name: Isaac Asimov

Date of Birth: January 2, 1920

Place of Birth: Petrovichi, Klimovichskiy Uyezd, Russia

Date of Death: April 6, 1992 (aged 72)

Place of Death: Brooklyn, New York, United States

Occupation: Writer, Professor of Biochemistry

Father: Judah Asimov

Mother: Anna Rachel (Berman) Asimov

Spouse/Ex: Gertrude Blugerman (m. 1942-1973), Janet Opal Jeppson (m. 1973-1992)

Children: David Asimov, Robyn Asimov

Early Life

An American author and biochemist, a highly successful and prolific writer of science fiction and of science books for the layperson, Isaac Asimov were born on January 2, 1920, in Petrovichi, Russia, then part of the Smolensk district in the Soviet Union. Asimov was a prolific writer who wrote or edited more than 500 books and an estimated 90,000 letters and postcards. His books have been published in 9 of the 10 major categories of the Dewey Decimal Classification. Many, however, believe Asimov’s greatest talent was for, as he called it, “translating” science, making it understandable and interesting for the average reader.

Asimov’s most successful work was on hard science fiction and his most notable book is the ‘Foundation Series’. Asimov is also widely popular for his easy Physics, astronomy and mathematics books alongside his works on the Bible, William Shakespeare, and chemistry. Asimov was a brilliant professor of biochemistry at Boston University. Besides being a prolific writer, Asimov was also an integral part of (President) the American Humanist Association. Asimov is also known for his work as a civilian at the Philadelphia Navy Yard’s Naval Air Experimental Station during World War II. “Robotics” was a term coined by Asimov which went on to become a branch of technology. Along with Robert A. Heinlein and Arthur C. Clarke, Asimov was considered one of the “Big Three” science fiction writers during his lifetime.

Asimov also wrote mysteries and fantasy, as well as much nonfiction. Most of his popular science books explain concepts in a historical way, going as far back as possible to a time when the science in question was at its simplest stage. Examples include Guide to Science, the three volume set Understanding Physics, and Asimov’s Chronology of Science and Discovery. He wrote on numerous other scientific and non-scientific topics, such as chemistry, astronomy, mathematics, history, biblical exegesis, and literary criticism. He was president of the American Humanist Association. The asteroid 5020 Asimov, a crater on the planet Mars, a Brooklyn elementary school, and a literary award are named in his honor.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

An American writer specializing in the genre of science fiction, Isaac Asimov (æzɪmɒv) was born on January 2, 1920, in Petrovichi, Russia, then part of the Smolensk district in the Soviet Union. He was the first of three children of Juda and Anna Rachel Asimov. He is known to have celebrated his birthday on 2 January. His name in purely Russian is spelled as Isaak Ozimov. Isaac was 3 years old when his family shifted to the United States. His parents being Yiddish and English speakers, Asimov never learned how to speak proper Russian. Although his father made a good living, changing political conditions led the family to leave for the United States in 1923. The Asimovs settled in Brooklyn, New York, where they owned and operated a candy store.

Azimov is spelled Азимов in the Cyrillic alphabet. When the family arrived in the United States in 1923 and their name had to be spelled in the Latin alphabet, Asimov’s father spelled it with an S, believing this letter to be pronounced like Z (as in German), and so it became Asimov. This later inspired one of Asimov’s short stories, “Spell My Name with an S.” Asimov refused early suggestions of using a more common name as a pseudonym and believed that its recognizability helped his career. After becoming famous, he often met readers who believed that “Isaac Asimov” was a distinctive pseudonym created by an author with a common name.

Asimov received his formal education from several schools registered under New York City Public Schools which included Boys High School, in Brooklyn, New York. He moved to Seth Low Junior College studying for two years before joining Columbia University where he completed his remaining education for gaining his master’s degree. In 1939 Asimov received his graduation. Asimov completed his Master of Arts degree in chemistry in 1941 and returned to Columbia University in 1948 to gain his Ph.D. in biochemistry.

Personal Life

Isaac Asimov met his first wife, Gertrude Blugerman (1917, Toronto, Canada 1990, Boston, U.S.), on a blind date on February 14, 1942, and married her on July 26 the same year. The couple lived in an apartment in West Philadelphia while Asimov was employed at the Philadelphia Navy Yard (where two of his co-workers were L. Sprague de Camp and Robert A. Heinlein). Gertrude returned to Brooklyn while he was in the army, and they both lived there from July 1946, before moving to Stuyvesant Town, Manhattan, in July 1948. They moved to Boston in May 1949, then to nearby suburbs Somerville in July 1949, Waltham in May 1951, and finally West Newton in 1956. They had two children, David (born 1951) and Robyn Joan (born 1955). In 1970, they separated, and Asimov moved back to New York, this time to the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where he lived for the rest of his life.

On November 30, 1973, Asimov tied the knot again with Janet Opal Jeppson, a writer, and psychoanalyst. Jeppson wrote Norby Chronicles, a science fiction novel for young readers in collaboration with Isaac.

Isaac Asimov was a claustrophile: he enjoyed small, enclosed spaces. In the third volume of his autobiography, he recalls a childhood desire to own a magazine stand in a New York City Subway station, within which he could enclose himself and listen to the rumble of passing trains while reading. Asimov was afraid of flying, doing so only twice: once in the course of his work at the Naval Air Experimental Station and once returning home from Oahu in 1946. Consequently, he seldom traveled great distances. This phobia influenced several of his fiction works, such as the Wendell Urth mystery stories and the Robot novels featuring Elijah Baley. In his later years, Asimov found enjoyment traveling on cruise ships, beginning in 1972 when he viewed the Apollo 17 launch from a cruise ship. On several cruises, he was part of the entertainment program, giving science-themed talks aboard ships such as the RMS Queen Elizabeth II.

Isaac Asimov had very different habits. He liked to listen to the noise of trains passing by during his reading hours so he often enclosed himself. Asimov was a very good public speaker and he was very friendly to converse and discuss topics with.

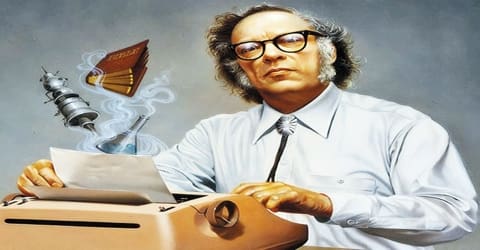

Career and Works

Isaac Asimov was highly interested in science fiction as a young kid. He extensively read popular pulp magazines which his father asked him not to read because Asimov’s father felt the magazines were useless. However, Asimov got his way with his father making him see the ‘science’ factor alive in the magazines which made them educational in nature. Asimov’s great interest in this field made him take up the pen at the age of 11 when he first started writing stories. When he turned 19, Asimov had honed the art of writing professional science fiction and his stories were sold to science fiction magazines of his time. Asimov discovered a community of people who were hugely interested in science fiction and they were called SF fandom or Science fiction fandom. Asimov got heavily influenced by the editor of ‘Astounding Science Fiction’, John W. Campbell who later became a personal friend of Asimov.

Asimov began contributing stories to science-fiction magazines in 1939. He sold his first story, “Marooned off Vesta” to Amazing Stories, but he was most closely associated with Astounding Science-Fiction and its editor, John W. Campbell, Jr., who became a mentor to Asimov. “Nightfall” (1941), about a planet in a multiple-star system that only experiences darkness for one night every 2,049 years, brought him to the front rank of science-fiction writers and is regarded as one of the genre’s greatest short stories.

Isaac Asimov spent three years during World War II working as a civilian chemist at the Philadelphia Navy Yard’s Naval Air Experimental Station, living in the Walnut Hill section of West Philadelphia from 1942 to 1945. In September 1945, he was drafted into the U.S. Army; if he had not had his birth date corrected while at school, he would have been officially 26 years old and ineligible. In 1946, a bureaucratic error caused his military allotment to be stopped, and he was removed from a task force days before it sailed to participate in Operation Crossroads nuclear weapons tests at Bikini Atoll. He served for almost nine months before receiving an honorable discharge on July 26, 1946. He had been promoted to corporal on July 11.

In 1940 Asimov began writing his robot stories (later collected in I, Robot 1950). In the 21st century, “positronic” robots operate according to the Three Laws of Robotics:

- A robot may not injure a human being, or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm;

- A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law; and

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Laws.

Isaac Asimov said that he used these ideas as the basis for “over two dozen short stories and three novels … about robots.” The three laws became so popular, and seemed so sensible, that many people believed real robots would eventually be designed according to Asimov’s basic principles. Also notable among Asimov’s science fiction works is the “Foundation” series. This group of short stories, published in magazines in the 1940s and then collected and reprinted in the early 1950s, was written as a “future history,” a story being told in a society of the future which relates events of that society’s history. Foundation, Foundation and Empire, and Second Foundation were enormously popular among science fiction fans. In 1966 the World Science Fiction Convention honored them with a special Hugo Award as the best all-time science fiction series. Even many years after the original publication, Asimov’s future history series remained popular in the 1980s, forty years after he began the series, Asimov added a new volume, Foundation’s Edge.

In 1948 Asimov completed his Doctorate degree after which he was appointed to the faculty of the Boston University School of Medicine. He remained here for a long time before deciding to run his non-teaching role at the University as he had already become an active writer from 1958. Asimov kept serving as an associate professor (he only held the title) but his full-time commitment was with writing. Boston University’s Mugar Memorial Library has archived all the personal papers noted and written out by Asimov from the period spanning from 1965 to his end days with the University. Asimov had even donated all these papers to the University on curator Howard Gottlieb’s request. The Asimov collection comprises of 464 boxes or seventy-one meters of shelf space.

By 1952, however, Asimov was making more money as a writer than from the university, and he eventually stopped doing research, confining his university role to lecturing students. In 1955 he was promoted to associate professor, which gave him tenure. In December 1957 Asimov was dismissed from his teaching post, with effect from 30 June 1958, because he had stopped doing research. After a struggle which lasted for two years, he kept his title, and on 18 October 1979, the university honored his writing by promoting him to full professor of biochemistry. Asimov’s personal papers from 1965 onward are archived at the university’s Mugar Memorial Library, to which he donated them at the request of curator Howard Gotlieb.

In 1941 Asimov brought out his 32nd story named “Nightfall” which became very popular and is often known to be the most famous science fiction stories of all time. Nightfall (was voted as “the best science fiction story ever” in 1968 by Science Fiction Writers of America) was the introduction of a new genre of writing which was more of a social science fiction bringing in a new trend in the 1940s. It was later brought out in a short story collection, ‘Nightfall and Other Stories’. By 1941 Asimov had sold (regularly) a great many stories to Astounding magazine which led the science fiction field. All of Asimov’s published science fiction stories and other writings were featured in Astounding from 1943 to 1949. Some other noted fictional works by Isaac Asimov include The Stars, like Dust (1951), The Currents of Space (1952), The Caves of Steel (1954), The Naked Sun (1957), Earth Is Room Enough (1957), Foundation’s Edge (1982), and The Robots of Dawn (1983).

Asimov was also author to many non-fiction writings of which the first was The Chemicals of Life (1954). Some more of his written scientific efforts include Inside the Atom (1956), The World of Nitrogen (1958), Life and Energy (1962), The Human Brain (1964), The Neutrino (1966), Science, Numbers, and I (1968), Our World in Space (1974), and Views of the Universe (1981). Furthermore, in addition to writing two autobiographies, Asimov also published the quarterly Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine which was founded by Davis Magazines. Famous for stating the Three Laws of Robotics, Isaac Asimov’s contributions to scientific literature have been acknowledged by esteemed awards such as Hugo, Nebula, and many honorary degrees.

In the late 1950s and 60s, Asimov stopped writing fictions. He published four adult novels two of which were mysteries. He increased his non-fiction writing after the launch of Sputnik in 1957. Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction had asked Asimov to regularly contribute for their monthly edition in the non-fiction column. Another bimonthly companion magazine ‘Venture Science Fiction Magazine’ which had dedicated themselves purely in serving popular science and Asimov got his full freedom as the magazine’s editor. First F&SF columns appeared in November 1958. Asimov also dedicatedly wrote about social issues and observations of his time in his essays “Thinking About Thinking” and “Science: Knock Plastic” (1967). He wrote many other essays dealing with society. Asimov wrote about the Bible in two parts bringing out ‘Asimov’s Guide to the Bible’ in two volumes, one covering the Old Testament in 1967 and the other covering the New Testament in 1969. Asimov was greatly interested in English Literature which guided him to write and publish ‘Asimov’s Guide to Shakespeare’ in 1970, ‘Asimov’s Annotated Paradise Lost’ in 1974 and ‘The Annotated Gulliver’s Travels’ in 1980.

Among Asimov’s late novels were expansions of previous short stories, written with Robert Silverberg, such as Nightfall (1990) and Child of Time (1991, based on “The Ugly Little Boy”). He published three volumes of autobiography: In Memory Yet Green: The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov, 1920-1954 (1979); In Joy Still Felt: .The Autobiography of Isaac Asimov, 1954-1978 (1980); and I, Asimov: A Memoir (1994, Hugo Award for best nonfiction book).

Awards and Honor

Issac Asimov won more than a dozen annual awards for particular works of science fiction and a half dozen lifetime awards. He also received 14 honorary doctorate degrees from universities.

Death and Legacy

In 1977, Isaac Asimov suffered a heart attack. In December 1983, he had triple bypass surgery, during which he contracted HIV from a blood transfusion. When his HIV status was understood, his physicians warned that if he publicized it, the anti-AIDS prejudice would likely extend to his family members. Asimov died in New York City on April 6, 1992, and was cremated. Asimov’s brother Stanley had reported heart and kidney failure which had possibly caused Asimov’s death. Ten years later, after most of Asimov’s physicians had died, Janet and Robyn Asimov agreed that the HIV story should be made public; Janet revealed it in her edition of his autobiography, It’s Been a Good Life.

His many books on science, explaining everything from how nuclear weapons work to the theory of numbers, take complicated information and turn it into readable, interesting writing. Asimov also loved his work as a teacher and discovered that he was an entertaining public speaker. Before his death in 1992, Asimov commented, “I’m on fire to explain, and happiest when it’s something reasonably intricate complicated which I can make clear step by step. It’s the easiest way I can clarify explain things in my own mind.”

Asimov believed his most enduring contributions would be his “Three Laws of Robotics” and the Foundation series. Furthermore, the Oxford English Dictionary credits his science fiction for introducing into the English language the words “robotics”, “positronic” (an entirely fictional technology), and “psychohistory” (which is also used for a different study on historical motivations). Asimov coined the term “robotics” without suspecting that it might be an original word; at the time, he believed it was simply the natural analog of words such as mechanics and hydraulics, but for robots. Unlike his word “psychohistory”, the word “robotics” continues in mainstream technical use with Asimov’s original definition. Star Trek: The Next Generation featured androids with “positronic brains” and the first-season episode “Datalore” called the positronic brain “Asimov’s dream”.

Asimov was greatly interested in History which made him write 14 popular history books, some of the notable ones being, ‘The Greeks: A Great Adventure’ (1965), ‘The Roman Republic’ (1966), ‘The Roman Empire’ (1967), ‘The Egyptians’ (1967) and ‘The Near East: 10,000 Years of History’ (1968).

Information Source: