Biography of Emily Brontë

Emily Brontë – English novelist and poet.

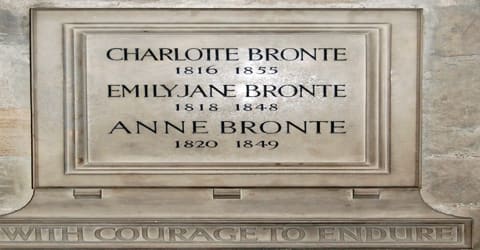

Name: Emily Jane Brontë

Penname: Ellis Bell

Date of Birth: 30 July 1818

Place of Birth: Thornton, West Riding of Yorkshire, England

Date of Death: 19 December 1848 (aged 30)

Place of Death: Haworth, West Riding of Yorkshire, England

Father: Patrick Brontë (1777–1861)

Mother: Maria Branwell

Occupation: Poet, novelist, governess

Early Life

Emily Brontë is best known for authoring the novel Wuthering Heights. She was the sister of Charlotte and Anne Brontë, also famous authors. She was born on 30 July 1818 in Market Street in the village of Thornton on the outskirts of Bradford, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, in Northern England.

Emily was perhaps the greatest of the three Brontë sisters, but the record of her life is extremely meager, for she was silent and reserved and left no correspondence of interest, and her single novel darkens rather than solves the mystery of her spiritual existence.

The sisters enjoyed writing poetry and novels, which they published under pseudonyms. As “Ellis Bell,” Emily wrote Wuthering Heights (1847) her only published novel which garnered wide critical and commercial acclaim. Emily Brontë died in Haworth, Yorkshire, England, on December 19, 1848, the same year that her brother, Branwell, passed away.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Emily Brontë, in full Emily Jane Brontë, pseudonym Ellis Bell, was born on 30 July 1818 in Market Street in the village of Thornton on the outskirts of Bradford, in the West Riding of Yorkshire, in Northern England, to Maria Branwell and an Irish father, Patrick Brontë. Her father had been a schoolteacher and tutor before becoming an Anglican minister. She grew up in Haworth in the bleak West Riding area of Yorkshire. She was the younger sister of Charlotte Brontë and the fifth of six children. In 1820, shortly after the birth of Emily’s younger sister Anne, the family moved eight miles away to Haworth, where Patrick was employed as perpetual curate; here the children developed their literary talents.

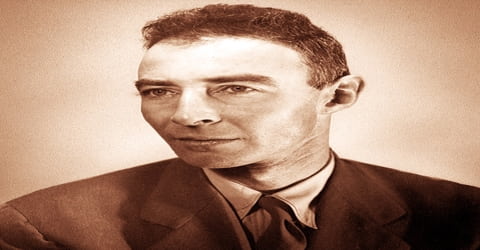

(The three Brontë sisters, in an 1834 painting by their brother Branwell Brontë. From left to right: Anne, Emily, and Charlotte.)

After the death of their mother in 1821, the children were left very much to themselves in the bleak moorland rectory. The children were educated, during their early life, at home, except for a single year that Charlotte and Emily spent at the Clergy Daughters’ School at Cowan Bridge in Lancashire. At the age of six on 25 November 1824, Emily joined her sisters at school for a brief period. When a typhoid epidemic swept the school, Maria and Elizabeth caught it. Maria, who may actually have had tuberculosis, was sent home, where she died. Emily was subsequently removed from the school, in June 1825, along with Charlotte and Elizabeth. Elizabeth died soon after their return home.

In 1835, when Charlotte secured a teaching position at Miss Wooler’s school at Roe Head, Emily accompanied her as a pupil but suffered from homesickness and remained only three months. In 1838 Emily spent six exhausting months as a teacher in Miss Patchett’s school at Law Hill, near Halifax, and then resigned.

Living in an isolated village, separated socially and intellectually from the local people, the Brontë sisters (Charlotte, Emily, and Anne) and their brother Patrick Branwell spent the majority of their time in made-up worlds. They described these imaginary worlds in poems and tales and in “magazines” written in miniature script on tiny pieces of paper. As the children grew older, their personalities changed. Emily and Anne created the realm of Gondal. Located somewhere in the north, it was, like West Riding, a land of wild moors (open, grassy areas unsuitable for farming). Unlike Charlotte and Patrick’s dream world called Angria, Gondal’s laws reflected those of the real world. But this did not mean that Emily found it any easier than her sister to live happily as a governess or schoolteacher, which seemed to be their only options for the future.

Brontë and her sister Charlotte traveled to Brussels in 1842 to study, but the death of their aunt Elizabeth forced them to return home.

Personal Life

Emily Brontë remains a mysterious figure and a challenge to biographers because information about her is sparse due to her solitary and reclusive nature. Charlotte Brontë remains the primary source of information about Emily, although as an elder sister, writing publicly about her shortly after her death, she is not a neutral witness. After Emily’s death, Charlotte rewrote her character, history and even poems on a more acceptable (to her and the bourgeois reading public) model. Charlotte presented Emily as someone whose “natural” love of the beauties of nature had become somewhat exaggerated owing to her shy nature, portraying her as too fond of the Yorkshire Moors, and homesick whenever she was away. According to Lucasta Miller, in her analysis of Brontë biographies, “Charlotte took on the role of Emily’s first mythographer.” In the Preface to the Second Edition of Wuthering Heights, in 1850, Charlotte wrote:

My sister’s disposition was not naturally gregarious; circumstances favored and fostered her tendency to seclusion; except to go to church or take a walk on the hills, she rarely crossed the threshold of the home. Though her feeling for the people around was benevolent, intercourse with them she never sought; nor, with very few exceptions, ever experienced. And yet she knew them: knew their ways, their language, their family histories; she could hear of them with interest, and talk of them with detail, minute, graphic, and accurate; but WITH them, she rarely exchanged a word.

In Queens of Literature of the Victorian Era (1886), Eva Hope summarises Emily’s character as “a peculiar mixture of timidity and Spartan-like courage”, and goes on to say, “She was painfully shy, but physically she was brave to a surprising degree. She loved few persons, but those few with a passion of self-sacrificing tenderness and devotion. To other people’s failings she was understanding and forgiving, but over herself she kept a continual and most austere watch, never allowing herself to deviate for one instant from what she considered her duty.”

Career and Works

Emily Brontë did not mind the isolation of Haworth, as being outdoors in the moors gave her a feeling of freedom. Here she experienced the world in terms of forces of nature that cannot be considered good or evil. She believed in the presence of supernatural powers (such as ghosts or spirits) and began to express her feelings in poems such as “To Imagination,” “The Prisoner,” “The Visionary,” “The Old Stoic,” and “No Coward Soul.”

In 1844, Emily began going through all the poems she had written, recopying them neatly into two notebooks. One was labeled “Gondal Poems”; the other was unlabelled. Scholars such as Fannie Ratchford and Derek Roper have attempted to piece together a Gondal storyline and chronology from these poems. In the autumn of 1845, Charlotte discovered the notebooks and insisted that the poems be published. Around this time she had written one of her most famous poems, “No coward soul is mine”, probably as an answer to the violation of her privacy and her own transformation into a published writer. Despite Charlotte’s later claim, it was not her last poem.

In 1845 Charlotte came across some poems by Emily, and this led to the discovery that all three sisters Charlotte, Emily, and Anne had written verse. A year later they published jointly a volume of verse, Poems by Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell, the initials of these pseudonyms being those of the sisters; it contained 21 of Emily’s poems, and a consensus of later criticism has accepted the fact that Emily’s verse alone reveals true poetic genius. The venture cost the sisters about £50 in all, and only two copies were sold.

The Athenaeum reviewer praised Ellis Bell’s work for its music and power, singling out his poems as the best: “Ellis possesses a fine, quaint spirit and an evident power of wing that may reach heights not here attempted”, and The Critic reviewer recognized “the presence of more genius than it was supposed this utilitarian age had devoted to the loftier exercises of the intellect.”

Again publishing as Ellis Bell, Brontë published her defining work, Wuthering Heights, in December 1847. The complex novel explores two families the Earnshaws and the Lintons across two generations and their stately homes, Wuthering Heights and Thrushcross Grange. Heathcliff, an orphan taken in by the Earnshaws, is the driving force between the action in the book. He first motivated by his love for his Catherine Earnshaw, then by his desire for revenge against her for what he believed to be rejection.

Wuthering Heights, when published in December 1847, did not fare well; critics were hostile, calling it too savage, too animal-like, and clumsy in construction. Only later did it come to be considered one of the finest novels in the English language.

Set in the moors, it is a story of love and revenge involving a character named Heathcliff, who was abandoned by his parents as an infant, and his effect on two neighboring families. Critical reaction was negative, at least partly due to the many errors in the first printing. Later Wuthering Heights came to be considered one of the great novels of all time.

Although a letter from her publisher indicates that Emily had begun to write a second novel, the manuscript has never been found. Perhaps Emily or a member of her family eventually destroyed the manuscript, if it existed, when she was prevented by illness from completing it. It has also been suggested that, though less likely, the letter could have been intended for Anne Brontë, who was already writing The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, her second novel.

Awards and Honor

Interest in Brontë’s work and life remains strong today. The parsonage where Brontë spent much of her life is now a museum. The Brontë Society operates the museum and works to preserve and honor the work of the Brontë sisters.

Death and Legacy

Emily Brontë died of tuberculosis on December 19, 1848, nearly two months after her brother, Branwell, succumbed to the same disease. Her sister Anne also fell ill and died of tuberculosis the following May. On the morning of 19 December 1848, Charlotte, fearing for her sister, wrote this:

She grows daily weaker. The physician’s opinion was expressed too obscurely to be of use he sent some medicine which she would not take. Moments so dark as these I have never known I pray for God’s support to us all.

Emily had grown so thin that her coffin measured only 16 inches wide. The carpenter said he had never made a narrower one for an adult. She was interred in the Church of St Michael and All Angel’s family vault in Haworth.

Information Source: