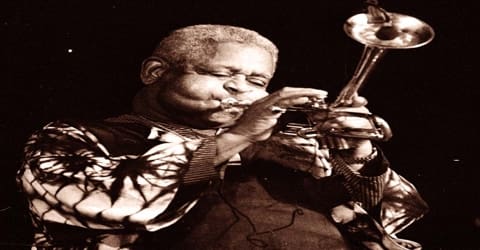

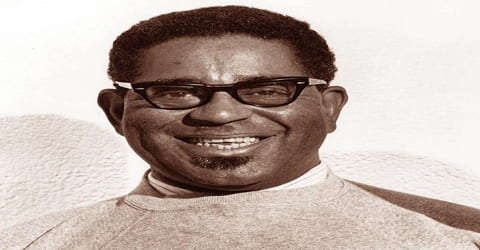

Biography of Dizzy Gillespie

Dizzy Gillespie – American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer, and singer.

Name: John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie

Date of Birth: October 21, 1917

Place of Birth: Cheraw, South Carolina, United States

Date of Death: January 6, 1993 (aged 75)

Place of Death: Englewood, New Jersey, United States

Occupation: Musician, Composer

Father: James

Mother: Lottie Gillespie

Spouse/Ex: Lorraine Willis (m. 1940-1993)

Children: Jeanie Bryson

Early Life

An American jazz trumpeter, composer, and bandleader who was one of the seminal figures of the bebop movement, Dizzy Gillespie was born in South Carolina, the U.S. on October 21, 1917, the youngest of nine children of James and Lottie Gillespie. Gillespie was a trumpet virtuoso and improviser, building on the virtuoso style of Roy Eldridge but adding layers of harmonic and rhythmic complexity previously unheard in jazz. His combination of musicianship, showmanship, and wit made him a leading popularizer of the new music called bebop. His beret and horn-rimmed spectacles, his scat singing, his bent horn, pouched cheeks, and his light-hearted personality provided some of bebop’s most prominent symbols.

Unusually gifted from childhood, he learned to play the piano from the age of four, taught himself trombone and trumpet at the age of twelve and began his career in music at the age of seventeen. Soon his radically fresh style of trumpet playing caught the attention of Mario Bauza, the Godfather of Afro-Cuban jazz, and through him, he met many other musicians with whom he developed the Afro-Cuban music.

One of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time (some would say the best), Gillespie was such a complex player that his contemporaries ended up copying Miles Davis and Fats Navarro instead, and it was not until Jon Faddis’ emergence in the 1970s that Dizzy’s style was successfully recreated. Somehow, Gillespie could make any “wrong” note fit, and harmonically he was ahead of everyone in the 1940s, including Charlie Parker. Unlike Bird, Dizzy was an enthusiastic teacher who wrote down his musical innovations and was eager to explain them to the next generation, thereby ensuring that bebop would eventually become the foundation of jazz.

However, he is best known as one of the proponents of bebop, a modern form of jazz music, which he developed with Charlie Parker and others. In the later part of his career, he toured extensively, sharing his knowledge with younger artists, helping them to overcome their shortcomings and develop their own styles. Today, he is remembered as the greatest trumpeter that the 20th century had ever produced.

Gillespie taught and influenced many other musicians, including trumpeters Miles Davis, Jon Faddis, Fats Navarro, Clifford Brown, Arturo Sandoval, Lee Morgan, Chuck Mangione, and balladeer Johnny Hartman.

Scott Yanow wrote, “Dizzy Gillespie’s contributions to jazz were huge. One of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time, Gillespie was such a complex player that his contemporaries ended up being similar to those of Miles Davis and Fats Navarro instead, and it was not until Jon Faddis’s emergence in the 1970s that Dizzy’s style was successfully recreated… Arguably Gillespie is remembered, by both critics and fans alike, as one of the greatest jazz trumpeters of all time”.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Dizzy Gillespie, by name of John Birks Gillespie, was born on October 21, 1917, in Cheraw, South Carolina, the U.S. His father, James Gillespie, a bricklayer by profession, was also a leader of the local band. His mother’s name was Lottie Gillespie. He was the youngest of his parents’ nine children. As the son of a musician, John was exposed to different types of musical instruments from childhood. Also having extraordinary musical talent, he learned to play the piano from the age of four.

The unexpected death of his father when Gillespie was ten instilled the boy with a drive to learn the trumpet, and he soon added on trombone and cornet. Contrarily, his talent earned him a place in the school band. Radio encounters with the music of Roy Eldridge, an early jazz trumpet legend, inspired the youngster to concentrate on trumpet.

However, Gillespie did not have any direction until one night he heard David Roy Eldridge play on the radio. He now took him up like his idol, dreaming of becoming a jazz player one day. Gillespie won a music scholarship to the Laurinburg Institute in North Carolina which he attended for two years before accompanying his family when they moved to Philadelphia. There he joined a band led by Frankie Fairfax. Gillespie’s musical career had begun.

Personal Life

In August 1937 Gillespie met a young dancer named Lorraine Willis who worked a Baltimore-Philadelphia, New York City circuit which included the Apollo Theater. Willis was not immediately friendly but Gillespie was attracted anyway and the two got married on May 9, 1940. They remained together until his death.

Gillespie also had a daughter, Jeanie Bryson, born out of a liaison with songwriter Connie Bryson. She is also a celebrated singer, specializing in a combination of jazz, pop, and Latin music.

Born a Christian, Dizzy Gillespie converted to the Bahá’í faith in 1968. Because of the universal nature of his faith, he saw himself as a global citizen and a musical messenger. He also took great interest in his African heritage.

Apart from his music, this famous trumpeter was also known for his swollen cheeks and his trademark trumpet, which had its bell angled at forty-five degree.

Career and Works

In 1935, seventeen-year-old John Birks Gillespie began his career with Frank Fairfax Orchestra. It was here that he earned his nickname ‘Dizzy’ for his unpredictable and yet funny behavior. During this period, not yet having a style of his own, he mostly cloned his hero David Roy Eldridge. Gillespie’s penchant for clowning and capriciousness earned him the nickname Dizzy. In 1937 he was hired for Eldridge’s former position in the Teddy Hill Orchestra and made his recording debut on Hill’s version of “King Porter Stomp.”

After a move to New York in 1937, Dizzy held positions in bands led by Teddy Hill, Al Cooper, and others, culminating in a spot in the band led by Cab Calloway, a famous singer, and bandleader. The Cab Calloway band recorded some of Dizzy’s finest early solos, including the 1940 solo on the tune ‘Pickin’ the Cabbage.’

In the late 1930s and early ’40s, Gillespie played in a number of bands, including those led by Cab Calloway, Ella Fitzgerald, Earl Hines, Duke Ellington, and Billy Eckstine. He also took part in many late-night jam sessions at Minton’s Playhouse, a New York City nightclub, and was among the club’s regulars who pioneered the bebop sound and style (others included Charlie Parker, Charlie Christian, Thelonious Monk, and Max Roach).

Also in 1937, Gillespie went with the band on a European tour, visiting England and France, with ‘The Cotton Club Show.’ On his return, he worked freelance for one year. During this period, he experimented with music, creating a style of his own. Soon, his music attracted the attention of Mario Bauza, the Godfather of Afro-Cuban jazz, then a member of the Chick Webb’s Orchestra. Later when in 1938 he joined Cab Calloway Orchestra, he convinced Calloway to hire Dizzy.

Thus in 1939, Dizzy joined Cab Calloway on the recommendation of Bauza. Unfortunately, he could not develop a rapport with Calloway as the later did not consider him to be a good musician. In spite of that, one of Dizzy’s first compositions, ‘Pickin the Cabbage’ was recorded with this band.

During his tenure with Calloway, Dizzy met a young alto saxophonist named Charlie Parker. The two hit it off, and before long were co-leading an after-hours jam session in New York which featured some of the city’s hottest jazz musicians. Dizzy’s relationship with Calloway was ultimately ill-fated, and following a 1941 dispute that came to blows onstage, he was fired from the band. While Dizzy moved through other bands – including those led by singer Ella Fitzgerald and vibraphonist Earl Hines – he also continued playing in small groups with Charlie Parker and even led his own big band for a time.

In 1944 the first bebop recording session included Gillespie’s “Woody ’n’ You” and featured Gillespie and Coleman Hawkins. Ultimately, Charlie Parker and Gillespie were regarded as cofounders of the bebop movement; the two worked together in several small groups in the 1940s and early ’50s. Although Parker was easily irritated by Gillespie’s onstage antics, their musical relationship seemed to benefit from their personal friction and their competitive solos were inventive, even inspired.

After a notorious altercation between the two men, Calloway fired Gillespie in late 1941. The incident is recounted by Gillespie and Calloway’s band members Milt Hinton and Jonah Jones in Jean Bach’s 1997 film, The Spitball Story. Calloway disapproved of Gillespie’s mischievous humor and his adventuresome approach to soloing. According to Jones, Calloway referred to it as “Chinese music”. During rehearsal, someone in the band threw a spitball. Already in a foul mood, Calloway blamed Gillespie, who refused to take the blame. Gillespie stabbed Calloway in the leg with a knife. Calloway had minor cuts on the thigh and wrist. After the two men were separated, Calloway fired Gillespie. A few days later, Gillespie tried to apologize to Calloway, but he was dismissed. During his time in Calloway’s band, Gillespie started writing big band music for Woody Herman and Jimmy Dorsey. He then freelanced with a few bands, most notably Ella Fitzgerald’s orchestra, composed of members of the Chick Webb’s band.

Gillespie formed his own orchestra in the late 1940s, and it was considered to be one of the finest large jazz ensembles. Noted for complex arrangements and instrumental virtuosity, its repertoire was divided between the bop approach from such arrangers as Tadd Dameron, John Lewis, George Russell, and Gillespie himself and Afro-Cuban jazz (or, as Gillespie called it, “Cubop”) in such numbers as “Manteca,” “Cubano Be,” and “Cubano Bop,” featuring conga drummer Chano Pozo. Gillespie formed other bands sporadically throughout the remainder of his career, but he played mostly in small groups from the 1950s onward.

Gillespie did not serve in World War II. At his Selective Service interview, he told the local board, “in this stage of my life here in the United States whose foot has been in my ass?” He was classified 4-F. In 1943, he joined the Earl Hines band. Gillespie said of the Hines band, “people talk about the Hines band being ‘the incubator of bop’ and the leading exponents of that music ended up in the Hines band. But people also have the erroneous impression that the music was new. It was not. The music evolved from what went before. It was the same basic music. The difference was in how you got from here to here to here … naturally, each age has got its own shit.”

In 1943, Dizzy Gillespie moved to Earl Hines’ Grand Terrace Orchestra. He had, by that time, met Charlie Parker at Harlem and was immensely impressed by his music. On his recommendation, Parker was appointed for an eight month’s gig at Hine’s. However, their collaboration actually started in 1944, when Billy Eckstine opened his own big band and both Dizzy and Parker went with him. In 1945, Gillespie left Eckstine’s band because he wanted to play with a small combo. A “small combo” typically comprised no more than five musicians, playing the trumpet, saxophone, piano, bass, and drums.

Towards the end of 1945, Dizzy and Charlie embarked on a six-week tour to Hollywood and from 10 December 1945 to 4 February 1946, played at Billy Berg’s. By the time the tour ended, they had given shape to the first modern jazz style, later known as the bebop music. Unfortunately, the audience was not very enthusiastic about this new form of music and was rather confused. Undeterred, the duo kept working on it, knowing that it would be accepted sooner or later.

In his 40s-era projects with Parker, the duo broke away from the swing they had played in stage bands and began developing a new style of jazz, characterized by faster tempos, more complex harmonies, and high-density melodies featuring lots of notes. This new style, which began to be known as bebop, gave Dizzy a chance to showcase his virtuosity on the trumpet, particularly his high notes and ability to improvise ideas at breakneck speeds.

Gillespie compositions like “Groovin’ High”, “Woody ‘n’ You”, and “Salt Peanuts” sounded radically different, harmonically and rhythmically, from the swing music popular at the time. “A Night in Tunisia”, written in 1942, while he was playing with Earl Hines’ band, is noted for having a feature that is common in today’s music: a syncopated bass line. “Woody ‘n’ You” was recorded in a session led by Coleman Hawkins with Gillespie as a featured sideman on February 16, 1944 (Apollo), the first formal recording of bebop. He appeared in recordings by the Billy Eckstine band and started recording prolifically as a leader and sideman in early 1945.

Dizzy Gillespie returned to New York in early 1946 and continued leading a number of small combos before he was able to set up his big band. During this period, he was introduced to Cuban jazz percussionist Chano Pozo, with whom he began to develop Afro-Cuban music. Subsequently, he along with his orchestra appeared in ‘Jivin’ in Be-Bop’, a 1947 musical film produced by William D. Alexander. Also in 1947, he co-wrote (with Pozo) ‘Manteca’, considered as one of the earliest foundational tunes of Afro-Cuban jazz.

During 1948-1949, nearly every former swing band was trying to play bop, and for a brief period, the major record companies tried very hard to turn the music into a fad. By 1950, the fad had ended and Gillespie was forced, due to economic pressures, to break up his groundbreaking orchestra.

In 1948, Gillespie had a minor accident, as a result of which he lost the capacity to hit the B-flat above high C. Nonetheless, he continued leading his band, composing new pieces like ‘Oop Bob Sh’ Bam’, ‘Groovin’ High’, ‘Leap Frog’, ‘Salt Peanuts’ and ‘My Melancholy Baby.’

To many, Gillespie ranks as the greatest jazz trumpeter of all time, with the possible exception of Louis Armstrong. He took the saxophone-influenced lines of Roy Eldridge and executed them faster, with greater ease and harmonic daring, playing his jagged melodies with abandon, reaching into the highest registers of the trumpet range, and improvising into precarious situations from which he seemed always to extricate himself. Gillespie helped popularize the interval of the augmented eleventh (flat fifth) as a characteristic sound in modern jazz, and he used certain stock phrases in his improvisations that became clichés when two generations of jazz musicians incorporated them into their own solos. His late 1940s look beret, horn-rim glasses, and goatee became the unofficial “bebop uniform” and a precursor to the beatnik styles of the 1950s. Other personal trademarks included his bent-bell trumpet and his enormous puffy cheeks that ballooned when playing. Gillespie was also a noted composer whose songbook is a list of bebop’s greatest hits; “Salt Peanuts,” “Woody ’n’ You,” “Con Alma,” “Groovin’ High,” “Blue ’n’ Boogie,” and “A Night in Tunisia” all became jazz standards.

In 1950, Gillespie was forced to break his band because of financial reasons. Thereafter, he worked solo, often teaming up with Charlie Parker. The Massey Hall concert in 1953 was the last major program, in which they teamed up together. The year 1953 was also the one in which he acquired his trademark. In a party on January 6, somebody sat on his trumpet, bending its bell upward in a 45-degree angle. Interestingly, he liked the sound better and from that point, bells of his trumpets were similarly bent.

In 1956 Gillespie organized a band to go on a State Department tour of the Middle East which was extremely well received internationally and earned him the nickname “the Ambassador of Jazz”. During this time, he also continued to lead a big band that performed throughout the United States and featured musicians including Pee Wee Moore and others. This band recorded a live album at the 1957 Newport jazz festival that featured Mary Lou Williams as a guest artist on piano.

After the orchestra broke up, Gillespie went back to leading small groups, featuring such sidemen in the 1960s as Junior Mance, Leo Wright, Lalo Schifrin, James Moody, and Kenny Barron. He retained his popularity, occasionally headed specially assembled big bands, and was a fixture at jazz festivals. In the early ’70s, Gillespie toured with the Giants of Jazz and around that time his trumpet playing began to fade, a gradual decline that would make most of his ’80s work quite erratic.

Gillespie’s most famous contributions to Afro-Cuban music are “Manteca” and “Tin Tin Deo” (both co-written with Chano Pozo); he was responsible for commissioning George Russell’s “Cubano Be, Cubano Bop”, which featured Pozo. In 1977, Gillespie met Arturo Sandoval during a jazz cruise to Havana. Sandoval toured with Gillespie and defected in Rome in 1990 while touring with Gillespie and the United Nations Orchestra.

At the last stage of his career, Gillespie traveled extensively all over the world, sharing his knowledge with younger artists. In 1989, apart from appearing in one hundred U.S. cities in thirty-one states, he gave three hundred performances in twenty-seven countries. In the same year, he also performed with two symphonies, recorded four albums and headlined in three television series. In was also in the 1980s when he became the leader of the United Nation Orchestra.

Gillespie was active up until early 1992. His last program was scheduled on November 26, 1992, at Carnegie Hall in New York City on the occasion of the centenary of the passing of Bahá’u’lláh, the founder of the Bahá’í Faith. However, he could not make it as he was too ill from cancer to be able to attend.

During the 1964 United States presidential campaign the artist, with tongue in cheek, put himself forward as an independent write-in candidate. Gillespie joined the Bahá’í religion in 1968. The universalist emphasis of his religion prodded him to see himself more like a global citizen and humanitarian, expanding on his interest in his African heritage. His spirituality brought out generosity and what author Nat Hentoff called an inner strength, discipline, and “soul force”. In the 1980s, Gillespie led the United Nation Orchestra. For three years Flora Purim toured with the Orchestra. She credits Gillespie with improving her understanding of jazz.

Awards and Honor

Dizzy Gillespie received the Grammy Award for Best Improvised Jazz in 1976, Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award in 1989, and Grammy Award for Best Large Jazz Ensemble Album in 1992. Later in 1995, he was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame.

In addition, Gillespie had received Paul Robeson Award from Rutgers University Institute of Jazz Studies (1972), Duke Ellington Award from the Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers (1989), and National Medal of Arts from President Bush (1989). Posthumously, he received Porin Award for Best Foreign Jazz Music Album (1998).

Gillespie also received the Kennedy Center Honors Award and the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers Duke Ellington Award for 50 years of achievement as a composer, performer, and bandleader (1990).

In 2002, Gillespie was posthumously inducted into the International Latin Music Hall of Fame for his contributions to Afro-Cuban music. He was honored on December 31, 2006, in A Jazz New Year’s Eve: Freddy Cole & the Dizzy Gillespie All-Star Big Band at The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts.

Death and Legacy

A longtime resident of Englewood, New Jersey Dizzy Gillespie died of pancreatic cancer on January 6, 1993, at the age of 75 and was buried in Flushing Cemetery, Queens, New York City. Mike Longo delivered a eulogy at his funeral.

Dizzy Gillespie is best remembered as one of the exponents of bebop, a modern form of jazz music. Although it was quite unpopular in the beginning as the audience was not yet ready for this new kind of jazz, it later gained much prominence. His compositions like ‘Groovin’ High’, ‘Woody ‘n’ You’ and ‘Salt Peanuts’, ‘Night in Tunisia’ and ‘Con Alma’ became highly popular. He is also remembered for his work on Afro-Cuban music. His most famous contributions to this genre of music are compositions like ‘Manteca’ and ‘Tin Tin Deo’, which he co-wrote with Chano Pozo, a Cuban jazz percussionist, singer, and composer.

As an active musical ambassador, Gillespie led several overseas tours sponsored by the U.S. State Department and traveled the world extensively, sharing his knowledge with younger players. During his last few years, he was the leader of the United Nations Orchestra, which featured such Gillespie protégés as Paquito D’Rivera and Arturo Sandoval. Gillespie’s memoirs, To Be, or Not…to Bop, were published in 1979.

Gillespie was inducted into the International Latin Music Hall of Fame for his contributions to Afro-Cuban music in 2002 and the New Jersey Hall of Fame in 2014. In addition, he has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame at 7057 Hollywood Boulevard.

Information Source: