Biography of Anna Pavlova

Anna Pavlova – Russian prima ballerina.

Name: Anna Pavlovna (Matveyevna) Pavlova

Date of Birth: February 12, 1881

Place of Birth: Ligovo, Saint Petersburg, Russian Empire

Date of Death: January 23, 1931 (aged 49)

Place of Death: The Hague, Netherlands

Occupation: Ballerina

Father: Lyubov Feodorovna Pavlova

Mother: Lyubov Feodorovna

Spouse/Ex: Victor Dandré (m. 1924–1931)

Early Life

Anna Pavlova was a famous Russian prima ballerina and choreographer, who was born on February 12, 1881, in St. Petersburg, Russia. She was a Russian prima ballerina of the late 19th and the early 20th centuries. She was a principal artist of the Imperial Russian Ballet and the Ballets Russes of Sergei Diaghilev. Pavlova is most recognized for the creation of the role The Dying Swan and, with her own company, became the first ballerina to tour ballet around the world. She toured South America and India.

The fact that Pavlova was not considered traditionally beautiful or that she was not of a physically built optimum for a ballerina never became a hindrance in her pursuit of becoming the most famous dancer of her days. She became fascinated with ballet after watching a performance as a young girl and decided to become a ballerina herself.

Her breakthrough performance was in The Dying Swan in 1905, which became her signature role. She joined the Ballet Russe in 1909 and formed her own company in 1911.

However, her early training proved to be difficult because of her arched feet and long, thin limbs technically she was not built to be a ballerina. But the young girl was determined not to let her physical imperfections come in the way of her dreams and trained under the best teachers of ballet to improve her technique. Pavlova compensated with her talents what she lacked physically. Through her determination and hard work she eventually became a world-class ballerina and even founded her own company. She was one of the earliest artists who toured extensively all over the world to stage her performances.

Childhood, Family and Educational Life

Anna Pavlova, in full Anna Pavlovna Pavlova, was born on February 12, 1881, in Ligovo, Saint Petersburg, Russia to unwed parents. Her mother, Lyubov Feodorovna was a laundress. Her father was banker Lazar Polyakov). Her mother’s second husband, Matvey Pavlov, is believed to have adopted her at the age of three, by which she acquired his last name.

From early on, Anna’s active imagination and love of fantasy drew her to the world of ballet. Looking back on her childhood, Anna Pavlova described her budding passion for ballet accordingly: “I always wanted to dance; from my youngest years…Thus I built castles in the air out of my hopes and dreams.”

Pavlova studied at the Imperial School of Ballet at the Mariinsky Theatre from 1891, joined the Imperial Ballet in 1899, and became a prima ballerina in 1906. Young Anna became fascinated with dancing after watching a performance of ‘The Sleeping Beauty’. Inspired, she auditioned for the famous Imperial Ballet School where she was accepted in 1891 at the age of ten.

She had severely arched feet and long, thin limbs which made training difficult. But she was not discouraged and spent long hours practicing and improving her technique under the coaching of renowned teachers like Christian Johansson, Enrico Cecchetti, and Nikolai Legat.

During her final year at the Imperial Ballet School, she performed many roles with the principal company. She graduated in 1899 at age 18, chosen to enter the Imperial Ballet a rank ahead of corps de ballet as a coryphée. She made her official début at the Mariinsky Theatre in Pavel Gerdt’s Les Dryades prétendues (The False Dryads). Her performance drew praise from the critics, particularly the great critic and historian Nikolai Bezobrazov.

Personal Life

Pavlova’s personal life was undramatic apart from occasional professional headlines, as when, in 1911, she quarreled with Mordkin. For some time she kept secret her marriage to her manager, Victor Dandré. The pair never had children.

Pavlova gave several charity performances to support Russian orphans of war. She adopted 15 girls into a home she had purchased and supported them with her earnings and donations from the Camp Fire Girls of America.

During her life, she had many pets including a Siamese cat, various dogs and many kinds of birds, including swans. Dandré indicated she was a lifelong lover of animals and this is evidenced by photographic portraits she sat for which often included an animal she loved. A formal studio portrait was made of her with Jack, her favorite swan.

Career and Works

Pavlova graduated to the Imperial Ballet in 1899 and rose steadily through the grades to become a prima ballerina in 1906. By this time she had already danced Giselle with considerable success. Her official debut was at the Mariinsky Theatre in Pavel Gerdt’s Les Dryades pretendues in 1899. Her performance was greatly appreciated by the great critic and historian Nikolai Bezobrazov.

Pavlova performed in various classical variations, pas de deux and pas de trois in such ballets as La Camargo, Le Roi Candaule, Marcobomba, and The Sleeping Beauty. Her enthusiasm often led her astray: once during a performance as the River Thames in Petipa’s The Pharaoh’s Daughter her energetic double pique turns led her to lose her balance, and she ended up falling into the prompter’s box. Her weak ankles led to difficulty while performing as the fairy Candide in Petipa’s The Sleeping Beauty, leading the ballerina to revise the fairy’s jumps en pointe, much to the surprise of the Ballet Master. She tried desperately to imitate the renowned Pierina Legnani, Prima ballerina assoluta of the Imperial Theaters. Once during class, she attempted Legnani’s famous fouettés, causing her teacher Pavel Gerdt to fly into a rage.

Pavlova was a very gifted ballerina and could perform in various classical variations such as pas de deux and pas de trios. Through her hard work and grace, she became a favorite of the old maestro Petipa who selected her to play the title role in ‘Paquita’.

She rose through the ranks quickly and became danseuse in 1902 and premiere danseuse in 1905, and was eventually named the prima ballerina in 1906. Her popularity soared and her fans started calling themselves the Pavlovatzi.

Pavlova’s career soon blossomed. With every performance, she gained increasing critical acclaim and subsequent fame. But it was in 1905 that Anna Pavlova made her breakthrough performance, when she danced the lead solo in choreographer Michael Fokine’s The Dying Swan, with music by Camille Saint-Saëns. With her delicate movements and intense facial expressions, Anna managed to convey to the audience the play’s complex message about the fragility and preciousness of life. The Dying Swan was to become Anna Pavlova’s signature role.

(Anna Pavlova in ‘The Dying Swan’)

Pavlova also choreographed several solos herself, one of which is The Dragonfly, a short ballet set to music by Fritz Kreisler. While performing the role, Pavlova wore a gossamer gown with large dragonfly wings fixed to the back. She had a rivalry with Tamara Karsavina. According to the film A Portrait of Giselle, Karsavina recalls a wardrobe malfunction. During one performance her shoulder straps fell and she accidentally exposed herself, and Pavlova reduced an embarrassed Karsavina to tears.

Almost immediately, in 1907, the pattern of her life began to emerge. That year, with a few other dancers, she went on a European tour to Riga, Stockholm, Copenhagen, Berlin, and Prague. She was acclaimed, and another tour took place in 1908. In 1909 the impresario Serge Diaghilev staged a historic season of Russian ballet in Paris, and Pavlova appeared briefly with the company there and later in London. But her experience of touring with a small group had given her a taste for independence, and she never became part of Diaghilev’s closely knit Ballets Russes. Her destiny was not, as was theirs, to innovate but simply to show the beauties of classical ballet throughout the world. While she was still taking leave from the Mariinsky Theatre, she danced in New York City and London in 1910 with Mikhail Mordkin.

Pavlova suffered from rigid feet and thus added a piece of hardwood to the sole of her pointe shoe to strengthen it. This was considered cheating during those times though it formed the basis for the creation of the modern pointe shoe.

In 1905, she performed the lead solo in Michael Fokine’s ‘The Dying Swan’ which had music by Camille Saint-Saens. Her frail and supple body allowed her to perform the delicate movements to perfection and this role came to be known as her signature role.

In the first years of the Ballets Russes, Pavlova worked briefly for Sergei Diaghilev. Originally she was to dance the lead in Mikhail Fokine’s The Firebird, but refused the part, as she could not come to terms with Igor Stravinsky’s avant-garde score, and the role was given to Tamara Karsavina. All her life Pavlova preferred the melodious “musique dansante” of the old maestros such as Cesare Pugni and Ludwig Minkus and cared little for anything else which strayed from the salon-style ballet music of the 19th century.

Pavlova was known to embark on long and grueling tours across the world to perform. Her first tour was in 1907 when she traveled all over Europe along with a group of dancers and performed in Berlin, Copenhagen, Prague among other major cities. The tour was highly successful.

In February 1910 Pavlova, performing with the brawny Moscow dancer Mikhail Mordkin (1880–1944), made her first appearance in America, at the Metropolitan Opera House. Most of the American audiences had never before seen classical ballet, and critics did not know how to describe what Pavlova did on stage, although all agreed that it was wonderful.

In 1911 Anna Pavlova took a major step in her career by forming her own ballet company. In so doing, Anna was able to retain complete creative control over performances and even choreograph her own roles. Anna put her husband, Victor Dandré, in charge of organizing her independent tours. For the final two decades of her ballet career, she toured with her company all over the world, as little girls watched in awe and were inspired to become dancers, the same way Anna had been at the Mariinsky Theatre all those years ago. Along with her company, she tirelessly toured all over the world for the next several years.

Once Pavlova left the Imperial Ballet in 1913, her frontiers were extended. For the rest of her life, with various partners (including Laurent Novikov and Pierre Vladimirov) and companies, she was a wandering missionary for her art, giving a vast number of people their introduction to ballet. Whatever the limitations of the rest of the company, which inevitably was largely a well-trained, dedicated band of young disciples, Pavlova’s own performances left those who watched them with a lasting memory of disciplined grace, poetic movement, and incarnate magic. Her quality was, above all, the powerful and elusive one of true glamour.

Pavlova’s final trip to Russia occurred in the summer of 1914. She was traveling through Germany on her way to London, England, when Germany declared itself at war with her homeland in August 1914. Pavlova’s protection from and obligations to the czar and his Maryinsky Theatre had come to an end.

In 1915, she appeared in the film The Dumb Girl of Portici, in which she played a mute girl betrayed by an aristocrat.

Pavlova also performed many ‘ethnic’ dances, some of which she learned from local teachers during her travels. In addition to the dances of her native Russia, she performed Mexican, Japanese, and East Indian dances. Supported by her interest, Uday Shankar, her partner in Krishna Radha (1923), went on to revive the long-neglected art of the dance in his native India. She also toured China.

The repertoire of Anna Pavlova’s company was in large part conventional. They danced excerpts or adaptations of Mariinsky successes such as Don Quixote, La Fille mal gardée (“The Girl Poorly Managed”), The Fairy Doll, or Giselle, of which she was an outstanding interpreter. The most famous numbers, however, were the succession of ephemeral solos, which were endowed by her with an inimitable enchantment: The Dragonfly, Californian Poppy, Gavotte, and Christmas are names that lingered in the thoughts of her audiences, together with her single choreographic endeavor, Autumn Leaves (1918).

In 1916, Pavlova produced a 50-minute adaptation of The Sleeping Beauty in New York City. Members of her company were largely English girls with Russianized names. One of her dancers, Kathleen Crofton, was reviewed by the ballet writer Cyril Johnson, he said that “her bourrées were like a string of pearls”. From 1918-1919 her company toured throughout South America, during which time Pavlova exerted an influence on the young American ballerina Ruth Page.

Pavlova’s enthusiasm for ethnic dances was reflected in her programs. Polish, Russian, and Mexican dances were performed. Her visits to India and Japan led her to a serious study of their dance techniques. She compiled these studies into Oriental Impressions, collaborating on the Indian scenes with Uday Shankar, later to become one of the greatest performers of Indian dance, and in this way playing an important part in the renaissance of the dance in India.

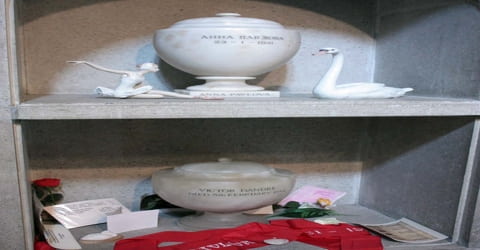

There are at least five memorials to Pavlova in London, England: a contemporary sculpture by Tom Merrifield of Pavlova as the Dragonfly in the grounds of Ivy House, a sculpture by Scot George Henry Paulin in the middle of the Ivy House pond, a blue plaque on the front of Ivy House, a statuette sitting with the urn that holds her ashes in Golders Green Crematorium, and the gilded statue atop the Victoria Palace Theatre.

Pavlova went to South America in 1917; in 1919 she visited Bahia and Salvador. A 1920–21 American tour represented Pavlova’s fifth major tour of the United States in ten years, and in 1923 the company traveled to Japan, China, India, Burma, and Egypt. South Africa, Australia, and New Zealand were given a glimpse of Pavlova in 1926, and the years 1927 and 1928 were dedicated to a European tour.

In 1930, when Anna Pavlova was 50 years old, her 30-year dance career had come to physically wear on her. She decided to take a Christmas vacation after wrapping up a particularly arduous tour in England. At the end of her vacation, she boarded a train back to The Hague, where she planned to resume dancing. On its way from Cannes to Paris, the train was in an accident. Anna was unharmed in the accident, but she was left waiting out the delay for 12 hours on the platform.

Pavlova is best known for creating the role of ‘The Dying Swan’ in the ballet of the same name. The ballad follows the last moments of the life of a swan which Pavlova portrayed with her delicate body movements and intense facial expressions. Considered her signature performance, she performed the dance around 4,000 times.

Her feet were extremely rigid, so she strengthened her pointe shoe by adding a piece of hardwood on the soles for support and curving the box of the shoe. At the time, many considered this “cheating”, for a ballerina of the era was taught that she, not her shoes, must hold her weight en pointe. In Pavlova’s case, this was extremely difficult, as the shape of her feet required her to balance her weight on her little toes. Her solution became, over time, the precursor of the modern pointe shoe, as pointe work became less painful and easier for curved feet. According to Margot Fonteyn’s biography, Pavlova did not like the way her invention looked in photographs, so she would remove it or have the photographs altered so that it appeared she was using a normal pointe shoe. She, on the other hand, did not wear Grishko’s, she wore Russian Pointe.

Awards and Honor

The Pavlova dessert is believed to have been created in honor of the dancer in Wellington during her tour of New Zealand and Australia in the 1920s. The nationality of its creator has been a source of argument between the two nations for many years.

Pavlova’s life was depicted in the 1983 film Anna Pavlova.

Pavlova’s dances inspired many artworks of the Irish painter John Lavery. The critic of The Observer wrote on 16 April 1911: ‘Mr. Lavery’s portrait of the Russian dancer Anna Pavlova caught in a moment of graceful, weightless movement … Her miraculous, feather-like flight, which seems to defy the law of gravitation’.

Death and Legacy

(The ashes of Anna Pavlova, above those of Victor Dandré, Golders Green Crematorium)

Pavlova contracted pneumonia during a tour and was advised to have an operation. However, she was informed that she would not be able to dance after the surgery. The dancer chose to die rather than giving up what she loved most. She died in The Hague, Netherlands, in the wee hours of the morning, on January 23, 1931. Her ashes were interred at Golders Green Cemetery, near the Ivy House where she had lived with her manager and husband, Victor Dandré, in London, England.

Victor Dandré wrote that Anna Pavlova died a half hour past midnight on Friday, January 23, 1931, with her maid Marguerite Létienne, Dr. Zalevsky and himself at her bedside. Her last words were, “Get my ‘Swan’ costume ready.”

Anna Pavlova was one of the most celebrated and influential ballet dancers of her time. Her passion and grace are captured in striking photographic portraits. Her legacy lives on through dance schools, societies and companies established in her honor, and perhaps most powerfully, in the future generations of dancers she inspired.

Pavlova’s ability to accept her role as spokesperson for her art, often with good humor and always with devotion and poise, brought vast audiences to her and eventually to the ballet itself. She was willing to perform in different venues, from the most famous theaters of Europe to London’s music halls or even New York’s gigantic Hippodrome. Pavlova’s private days were spent at Ivy House in London, where she kept a large collection of birds and animals, including a pair of pet swans. Her companion, manager, and perhaps husband (Pavlova gave different accounts of the exact nature of their relationship) was Victor Dandré, a fellow native of St. Petersburg.

Information Source: